This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s winter 2017 edition, “Advancing Critical Conversations: How to Get There from Here.” It was first published online on January 17, 2018.

These days, each morning’s news offers us yet another abhorrent reminder that the practice of leadership is anything but neutral. Although often portrayed as such in management literature and popular culture, leadership is not a generic set of behaviors that can be codified and transferred across generations, industries, values sets, or presidents. Instead, leadership is an expression of a group’s particular ethos, where ethos is defined as “the fundamental character or spirit of a culture; the underlying sentiment that informs the beliefs, customs, or practices of a group or society; dominant assumptions of a people or period.”1 Clearly, we have a multitude of leadership ethoses coexisting across political parties, industries, and communities in the United States. This is true in the nonprofit sector alone, which at over a million organizations is not of one mind but of many.

When we acknowledge that the practice of leadership is not neutral—that it is not apolitical—we necessarily embrace that nonprofits (that is, the people who work and govern in them) are going to make different leadership choices depending on their values and their politics, whether consciously or not. Moreover, we acknowledge that different leadership practices will create different results (or impacts) at the levels of the individual leader, teams of staff and board, organization, and field or sector, and in communities at large. The opportunity then—some might say the mandate—is twofold: as organizational and movement leaders, we must become conscious of how the practices of leadership we are employing and cultivating in others reflect (or not) the broader ethos of our work; and we must have our ears continuously attuned to how shifts in that broader ethos need to show up in our leadership practices, so that how we do our work keeps in step with what we want to see change in our organizations and in the world.

As someone with the privilege of engaging in day-to-day leadership practice as an executive director at CompassPoint—and who participates in the leadership discourse at the same time (given CompassPoint’s work)—I want to lift up some of the permanent shifts in the leadership ethos among progressive organizations that have become (and will continue to be) inspiration for new leadership practices. I am speaking explicitly to progressive organizational contexts, because I am not served—and nor are you, as reader—by rendering opaque the progressive values and politics I bring to this conversation. When we do that (whether as leaders or as leadership commentators), we perpetuate the illusion that we can all be trained to lead “the right way”—to believe that a generic “good leadership” will resonate with everyone.

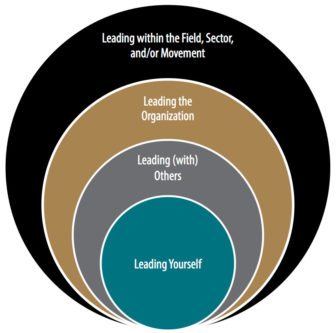

The Four Leadership Domains

Given that the impacts of leadership practices manifest at multiple levels of engagement, I will locate practices and their impacts in the four leadership domains identified in the graphic to the right.2

In the domain of leading yourself, perhaps the most significant shift in the leadership ethos is the mandate to examine one’s own identity and bring a consciousness of it into all leadership domains and contexts. Aspects of identity here include race, class, gender, tenure, and access to power both internal and external to the organization. Many of us have been acculturated to believe that we can lead and manage across race, power, and privilege without acknowledging the entitlement explicitly. For those of us who are white, middle or upper class, and/or educated within the established system, this has often meant an obliviousness to the effects of our privilege on our own analysis of situations, on our decision making, and on the quality of the relationships we can forge with diverse staff, boards, and constituents. At times, for marginalized groups, this pressure to not discuss identity in an organizational context fuels an internalized oppression that thwarts contributions to organizational impact and change. The belief now is that self-awareness and emotional intelligence—which are terms that have often been used in color- and class-blind ways—are dependent on our capacity to understand how identity influences our leadership.

So how can we support the open and ongoing reflection by all staff on the connections between their identities and their leadership practices? Leadership coaching can be extremely effective in this regard, although hiring coaches who bring identity consciousness to their work is obviously essential. If leadership is a practice, not a position, all staff should have access to coaching if at all possible. Peer coaching is an alternative if professional coaching is not financially feasible, or an excellent complement if it is. (And if you are providing professional coaching to senior staff and not others, consider the message that sends with respect to the leadership ethos.) Coaching methodologies are well suited to individuals’ exploration of why they are making certain leadership choices and to resetting intentions to achieve different results where desired. Another powerful practice is to staff affinity groups by identity—for example, race or gender. In my personal experience at CompassPoint, for instance, being part of a white staff affinity group has given me an unprecedented and invaluable space to explore how whiteness informs my leadership and to identify and work to rectify the results of my unexamined whiteness that have manifested destructively in our organization.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The concept of shared leadership, which has numerous potential structural and practical expressions, anchors the progressive leadership ethos in the next domain: leading (with) others. For decades, we have discussed the executive director job as not doable, as inevitably leading to burnout, as reinforcing a “martyr syndrome,” and so forth. But those assumptions still focus on the individual leader and what he or she needs. Today, when we think of leadership practice politically, shared leadership becomes about more than just sharing the work: it becomes about sharing the power. As leaders with positional power especially, how do we build the power of others through our approach to leadership? Sharing power may indeed make the job more doable, but that is not the only reason to share power. We are also trying to explore new, more equitable and constructive ways of holding power that will ripple out into all of the work we do.

The shift in practice here is a focus on building deep, transformative relationships across traditional lines of power. Sharing power is far more complex than “delegating” or “managing up,” so it requires an investment in relationship that is atypical, in my experience, in mainstream organizations. If I am going to share power with you—that is, take a risk with you—I have to know you and trust you. There are no shortcuts to knowing and trusting—no efficiencies, at least in the near term. A practice introduced at CompassPoint by my colleague Asha Mehta to support this kind of relationship building is called designing the alliance.3 This is a practice that can be used in relationships in all power directions, including between staff and board, and on teams. At its essence, the practice is about prioritizing the relationship by setting up understandings about what’s important to each person, how people react when they are upset, what they will do to reset when their relationship is inevitably challenged, and so forth. I have seen firsthand at CompassPoint how this practice has supported the development of powerful team relationships that have yielded dramatically stronger programmatic results. Prioritizing relationship building can change how you approach all kinds of staff and board interactions: meeting agendas that focus on storytelling rather than report outs; increased frequency of social gatherings; even reimagined work spaces, so that people connect with one another often over the course of the day. In short, it is relational organizations, not transactional ones, that will advance the practice of sharing power elegantly.

In the leading the organization domain, the opportunity is for progressive nonprofit organizations to view themselves as laboratories for new, more equitable and effective management structures, policies, and practices. For so long, we have tended to replicate the structures, policies, and practices of the for-profit sector, on the premise that they were “best practice,” more efficient, more protective of organizations from risk, and so on. It is noteworthy that we have done this even as we have seen (and even protested in our outward-facing work) the results of many of these practices in the for-profit sector for low-wage workers, people of color, women, and the environment. As we align our organizational leadership ethos with our broader ethos for social change, we can reimagine any number of traditional organizational practices, including how and who we hire, how we develop people, how we compensate people, how we engage with our constituents, how we communicate our impact, and so forth.

Human resources, for instance, is an organizational leadership arena ripe for new practices that align with a progressive ethos. One of the typically unchallenged assumptions of traditional human resources is confidentiality: confidential salaries, confidential performance reviews, confidential management-team decisions about whom to promote and whom to terminate. As my CompassPoint colleague Spring Opara said recently at an all-staff meeting, “Confidentiality is the enemy of equity.” She said this as we were discussing the work of a new organizational structure we had instituted: an equity panel of nonexecutive staff who now review all salary decisions for equity across race, gender, tenure, et cetera. The experience of moving to this transparent, nonconfidential salary approach has profoundly transformed my own view of management and deepened trust across CompassPoint with respect to the historically mistrust-inducing practice of setting staff compensation. The results of our reimagining of compensation through the lens of a progressive leadership ethos include: raising our compensation floor so that everyone makes a true living wage for the Bay Area; people of color who are emerging as important organizational leaders getting substantial raises and being better recognized for the contributions they are already making; eliminating the persistent discrepancies between administrative staff’s pay and program staff’s pay; and a collective belief that we can create our own structures and systems to reflect our own assumptions—not those of the dominant culture—about what work to value.

At the levels of our particular fields and the nonprofit sector overall—reflected in the leading within the field, sector, and/or movement domain—aligning our leadership ethos to our broader vision for change means confronting the nonprofit-industrial complex in our everyday decision making, just as we demand that other sectors and industries challenge their own self-preservationist habits and tactics. I believe that we have passed the moment when progressive leaders—both of nonprofits and philanthropies—can credibly ignore the nonprofit-industrial complex or pretend that their organizations are exempt from some degree of collusion with it. It is not a question of whether we each collude, but to what extent—and how much effort we should put toward using whatever influence we may have to highlight the consequences of that collusion and promote alternative approaches. This is important, because our legitimacy as agents of change is inevitably undermined when we don’t openly acknowledge the incentives that drive our choices.

In practical terms, this means leaders being willing to risk capital—financial, social, and political—in requesting and/or modeling changes to how our sector operates, so that it responds better to those for whom we exist. It means more powerful organizations being ever conscious of what resources they are garnering, what communities they are entering (and with whose permission), and how they are or are not partnering with other organizations. It means the leadership of our infrastructure organizations—nonprofit associations and networks of all kinds—using their collective power and platforms to challenge rather than uphold the status quo, even when some nonprofits may stand to lose something. And it certainly means leaders in philanthropy—with their disproportionate financial capital and influence—taking the necessary risks to finance and promote the work that is most needed to accelerate social change.

The first step is a series of conversations among your staff and board about how your current leadership practices reflect your shared beliefs and assumptions about where the world is going or needs to go. If you believe that racial justice is core to the change that needs to happen in the world, for instance, how can you better reflect that in your leadership structures, policies, and practices? If you believe that creativity and artistic expression are essential to that change, how can you better reflect that in your leadership structures, policies, and practices? If you believe that a deep ecology and respect for the Earth are core to that change, how can you better reflect that in your leadership structures, policies, and practices? Leadership and management are not generic methods but rather powerful potential means for experimenting toward a desired future.

Notes

- Dictionary.com, s.v. “ethos,” accessed November 29, 2017.

- Adapted by CompassPoint from the work of the Center for Creative Leadership, Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, Daniel Goleman, David Day, V. Jean Ramsey, and Jean Kantanbu Latting, and the Building Movement Project.

- Academy of Leadership Coaching & NLP; “Designing the Alliance: How to create healthier personal and professional relationships,” blog, accessed December 4, 2017.