May 26, 2015;Rolling Stone

Matt Taibbi has produced what we all expect from him, an in-your-face analysis of a social issue. This time, in the latest Rolling Stone, it’s a commentary on what happened during the lead-up to the protests in Baltimore. His lead-in is powerful:

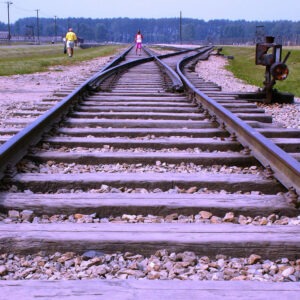

“When Baltimore exploded in protests a few weeks ago following the unexplained paddy-wagon death of a young African-American man named Freddie Gray, America responded the way it usually does in a race crisis: It changed the subject.

“Instead of using the incident to talk about a campaign of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of illegal searches and arrests across decades of discriminatory policing policies, the debate revolved around whether or not the teenagers who set fire to two West Baltimore CVS stores after Gray’s death were ‘thugs,’ or merely wrongheaded criminals.”

Taibbi notes that the debate has also focused on policing, as though the issue would be addressed with more body cameras (as Baltimore has already committed to provide) and better police training as opposed to dealing with “poverty, race, abuse, all that depressing inner city stuff.”

“Body cameras won’t fix it,” he writes. “You can’t put body cameras on a system.”

It is systemic across the nation, he says, and not just in Baltimore, though the stories he cites from Baltimore are horrendous:

“Go to any predominantly minority neighborhood in any major American city and you’ll hear the same stories: decades of being sworn at, thrown against walls, kicked, searched without cause, stripped naked on busy city streets, threatened with visits from child protective services, chased by dogs, and arrested and jailed not merely on false pretenses, but for reasons that often don’t even rise to the level of being stupid.”

He describes policing against inner city blacks as the equivalent of South Africa in the 1980s, but invisible to most white people because they “have literally no social interactions with black people, so they don’t hear about this every day.”

Taibbi puts much of the blame—and devotes much of his article to—the “Broken Windows” theory of policing that took hold under New York City police commissioner Bill Bratton during Rudy Giuliani’s terms as New York City mayor. He calls it “organized harassment” that had little or no impact on the crime rate. He goes through a variety of specifics of abusive police behavior, including an interesting story about one mayor who was as obsessed with Broken Windows metrics as anyone, former Baltimore mayor and now presidential candidate Martin O’Malley. In Baltimore, at the peak of the implementation of this strategy in 2005, 108,000 of the city’s 600,000 residents had been arrested, he says, a figure that seems incredibly high and hard to validate. Nonetheless, Taibbi’s point is that in this kind of policing system, huge numbers of citizens have formal encounters with the police even when they have done nothing to warrant police intervention.

The problem is that Taibbi’s analysis, brilliant, incisive, and deftly written, is long on why the police strategies employed in Baltimore and elsewhere are counterproductive, but short on options for the future—other than implicitly getting rid of this kind of policing. But what to put in its place? Taibbi credits Baltimore’s state attorney Marilyn Mosby for having “calmed down” the city by indicting the six police officers involved in the Freddie Gray incident for murder or manslaughter, and that may also be a recommended strategy: Don’t let police off the hook in the myriad of ways that Taibbi describes that police use to engage in inappropriate behavior without facing the consequences.

But since Freddie Gray’s death and the Mosby indictments, Baltimore has suffered through one of its three bloodiest months in the past two decades, which some people attribute to a calculated strategy on the part of police not to respond to many reported incidents. In a statement from the Baltimore police union distributed on Twitter, the police basically acknowledged the slowdown tactic:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Statement from Pres. Ryan: Baltimore violence surge. Mosby overrules SCOTUS “Illinois v. Wardlow” pic.twitter.com/NBIKxFsT6m

— Baltimore City FOP (@FOP3) May 28, 2015

How does our society protect and support the good cops who are doing their jobs in often unbelievably difficult circumstances while dropping the unnecessary and unproductive protection society often gives, sometimes unknowingly, to bad cops? The press has been focusing lately on “hero cops,” the guys who buy hungry people food or give kids rides to school, but that may miss the point, according to Stacey Patton and David J. Leonard writing in the Washington Post. Those stories, which they describe as “the essence of community policing,” meant to overcome “how little trust [the police have] earned in communities of color,” simply don’t do the trick.

“The deaths and brutality, the militarized occupation of black and Latino communities aren’t changed by officers reading ‘Goodnight Moon’ to children,” Patton and Leonard write. “Sure, such programs could address distrust and tensions, but something else would have a much more significant impact: ending daily harassment, thwarting violence and creating a culture of accountability.”

They add a powerful coda:

“The #BlackLivesMatter movement and those demanding racial justice are not asking for groceries, hugs and other kinds of paternalistic acts. It is demanding that the epidemic of police violence stop…Fixing flat tires and handing out ice cream does not address the longstanding structural inequalities that persist in cities like Baltimore, Ferguson and Cleveland…These feel-good stories are a tool of mass distraction. They tell us to look away from all those dead bodies and non-indictments…So don’t believe the hype. The police are not your friend. Books and dances or no books and dances, the baton, handcuffs and the gun remain their primary tool of interaction—particularly within communities of color.”

That is as powerful a challenge to the nonprofit sector as any regarding policing, and it may go against much of the approach of community policing as practiced by some nonprofits. For example, the report on one national community policing program, run by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (full disclosure: this author was a VP for LISC in the 1990s), has as its cover a picture of a large policeman handing a balloon to a little kid, just the kind of image that Patton and Leonard decry. The first page of the report has a picture of Bill Bratton, with a pull quote calling for police and community developers to jointly attack crime and blight problems. The report concludes with a nod to Bratton’s theory of policing:

“Just as the repair of broken windows reduces a community’s hospitality to crime and decay, the effective, responsive application of law enforcement makes it far more likely that investors, builders, residents, and merchants will want to improve the community, repair its broken windows, and continually build its assets.”

Taibbi doesn’t see the work of community policing nonprofits as helping improve conditions in urban neighborhoods. Patton and Leonard write somewhat disparagingly about community policing. Have the police killings and community reactions in Ferguson, North Charleston, Baltimore, and Cleveland, just to name a few places, caused nonprofits to reassess their thinking, strategies, and hopes for community policing?—Rick Cohen