This article is, with publisher permission, adapted from a more extensive journal article, “The Generativity Mindsets of Chief Executive Officers: A New Perspective on Succession Outcomes,” published last year by the Academy of Management Review.

What determines a company’s readiness for navigating a CEO transition? Our proposed answer builds upon prior research on CEO succession, viewed through a novel theoretical lens based on generativity theory and the mindset of the exiting CEO.

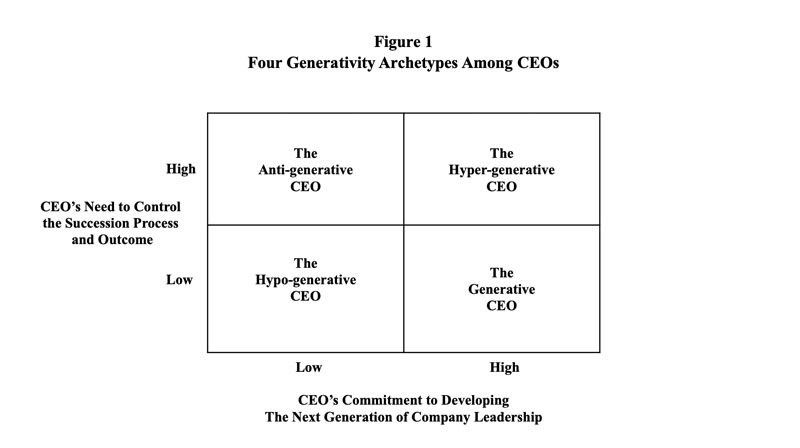

We assess exiting CEO stances by focusing on two key dimensions: a) the CEO’s degree of commitment to developing the next generation of company leadership, and b) the CEO’s degree of need to control the succession process and outcome. A given CEO’s place on these two dimensions generates an overall “generativity mindset.”

Since a given CEO could score low or high on the two scalar dimensions of generativity, this creates four archetypes, as shown in Figure 1: a) the hypo-generative CEO, who has little need to develop the next generation or to control the succession outcome; b) the generative CEO, who has a strong need to develop the next generation but little need to control the succession outcome; c) the hyper-generative CEO, who has a strong need to develop the next generation and a strong need to control the succession outcome; and d) the anti-generative CEO who has little need to develop the next generation and a strong need to control the succession outcome—specifically a strong need to thwart the rise of potential replacements, so as to stay in office as long as possible.

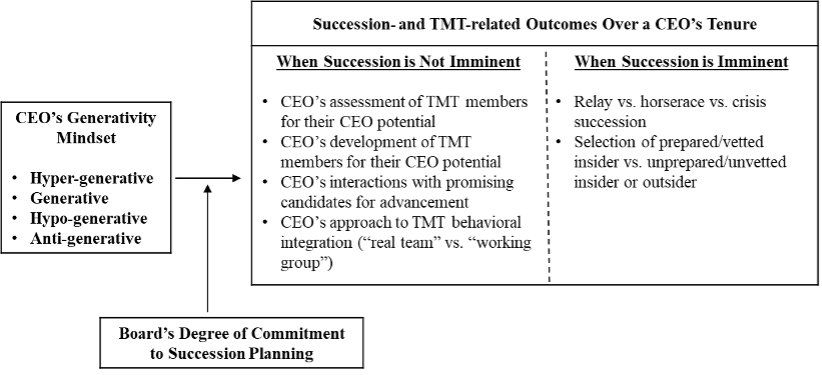

The final part of our model inserts the board of directors as a potentially moderating influence in all the foregoing relationships. In some cases, the board will encourage the CEO to join it in comprehensive preparation for his or her eventual departure. The greater the board’s commitment to succession planning, the more that hyper-, hypo-, and anti-generative CEOs will behave like generative CEOs, but their attainment of this ideal will vary widely. Our overall model is portrayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Even boards that are committed to careful and comprehensive succession planning cannot do so without the involvement of their incumbent CEOs. And since these individuals have varying personal philosophies about their eventual replacement, boards encounter various dilemmas in working with—or working around—their CEOs on succession-related matters.

The Concept of CEO Generativity

Although all CEOs face the prospect of eventually leaving their positions, their responses to this inevitability vary greatly. Before proceeding, it is important to distinguish generativity from the related concept of one’s desire to leave a legacy, or one’s legacy motivation. While a legacy motivation amounts to one’s (nearly universal) desire to make an enduring contribution and to be remembered for that contribution, generativity, based on psychologist Erik Erikson’s influential work on this topic, involves a personal striving to make a very specific type of contribution: mentoring, nurturing, and developing the next generation for its own primacy.

Like other humans, CEOs may indeed have strong needs to leave enduring signs of their handiwork. For CEOs, such legacies might be manifested in the brands, balance sheets, products, technologies, and physical facilities that survive them. It is quite another thing, however, to be intent on developing the people—or a specific person—who will be one’s replacement and help oversee this broader legacy.

One’s tendency toward generativity is triggered by a recognition of mortality and a desire to form intimate bonds with the future generations. Applying this dimension to the CEO context, we envision CEOs as varying in their degree of commitment to developing the next generation of firm leadership. Among CEOs, this commitment would be manifested in a CEO’s mindfulness about eventual departure as well as concerted involvement in helping to prepare the next round of leaders.

An absence of such commitment would be manifested in a CEO’s inattentiveness to, or even resistance to, eventual departure, as well as a failure to prepare the next round of leaders. These latter CEOs may be excellent in many aspects of managing and leading, but they are not attuned to identifying or developing their successors.

Four CEO Mindsets

Combined, this provides two dimensions—the degree to which CEOs prioritize leadership development and the degree to which they seek to control the succession process. CEOs can be high or low on each, resulting in four distinct orientations.

The hypo-generative CEO has little commitment to developing the next generation of leaders and little need to control the succession process. This CEO may be primarily oriented toward demonstrating a mastery in running the business—launching new products, streamlining operations, executing acquisitions, and so on—but not toward developing the next round of leaders.

The generative CEO has a strong need to develop the next generation of leaders but has little need to control the succession process or outcome. Such a CEO is intent on leaving the firm in capable hands but is not wedded to any specific candidate. As such, this CEO comes the closest to “partnering” with the board.

The hyper-generative CEO has a strong commitment to developing the next company leader and a strong need to control the succession outcome. The hyper-generative CEO is intent on engineering the selection of that one individual who seems most likely to adhere to the CEO’s priorities and practices.

Finally, the anti-generative CEO has little commitment to developing the next round of leadership and a strong need to control the succession outcome. This CEO rejects, consciously or sub-consciously, the central premise of generativity—that others must eventually replace us. They do this by attempting to cling to their positions as long as possible and by seeing to it that viable internal replacements are not available.

Succession Consequences of the Four CEO Mindsets

A CEO’s generativity mindset surfaces not only as exit draws near but, instead, is manifested throughout a CEO’s tenure. Indeed, even when their departures seem distant, CEOs’ respective generativity mindsets emerge and gain salience in multiple ways. Some CEOs—more than others—have the capacity and inclination to reflect on their eventual replacement, even when their departure is not imminent. This shows up both in their leadership development and management team practices.

CEO attitudes toward leadership development

For the generative CEO, a host of succession-related thoughts and actions will emerge, even though succession is not yet imminent. This CEO will start assessing top management team members not only for their effectiveness in their current posts but also for their potential to become CEOs themselves.

The hypo-generative CEO, who has little commitment to developing the next generation and little need to control the succession process, does not think much about eventual departure, especially when it is not imminent. This CEO is strictly focused on near-term performance and, thus, assesses executives for their effectiveness in their current roles but not for their growth potential.

The hyper-generative CEO, like the generative CEO, begins to have serious thoughts about succession, even when departure is not imminent. However, given this CEO’s strong need to control the succession outcome, coupled with a strong commitment to develop his or her eventual replacement, the hyper-generative CEO tries to orchestrate a more controlled and tightly circumscribed succession planning process, focusing on identifying a close disciple.

Finally, even when succession is not imminent, the anti-generative CEO looks more for signs of ambition than signs of talent, in apprehension that he or she might find someone who aspires to be CEO. With a strong desire to stay in the job, this CEO will maintain a skeptical eye when assessing top management team members, generally overlooking their talents and possibly even denigrating those talents in his or her own mind and in reports to the board.

Communicating with executives about their CEO potential

CEOs’ generativity mindsets will also be manifested in how CEOs communicate their assessments to individual executives.

Generative CEOs, committed to developing future leaders, will not only assess executives but also communicate their frank and comprehensive assessments to multiple executives. This includes acknowledging manager strengths and weaknesses in their current roles, but also openly discussing prospects for advancement and—as importantly—what is needed to maximize those chances.

In contrast, hypo-generative CEOs, generally uninterested in succession planning, may have ample discussions with their management team members about their effectiveness in their current roles, and how that effectiveness might be improved, but will tend not to discuss executives’ advancement potential.

The hyper-generative CEO adopts an intensely close relationship with his or her favored subordinate, with an eye toward both assuring the person’s retention and transmitting one’s philosophy and priorities. This CEO will work closely with that favored individual, clearly state expectations he or she has for that person, and openly exchange thoughts and feedback on an ongoing basis. Communications with other top management team members, however, will be less intimate, without any recognition of their potential beyond their current posts.

Anti-generative CEOs may have made private assessments about executives’ leadership potential, but communicating these assessments is a different matter. For the anti-generative CEO, any top management team members who show potential—or who especially show aspirations—beyond their current roles are seen as threats.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Professional development

Beyond possibly communicating their assessments to executives, CEOs may (or may not) provide extra-role developmental opportunities for top management team members who are deemed to have some potential for advancement. Typically designed to “stretch” executives beyond their proven repertoires, these extra-role developmental initiatives serve an additional purpose of providing the CEO yet more data for assessing the executives’ advancement potential.

CEOs’ generativity mindsets will greatly influence their respective approaches to developing top management team members for potential advancement.

In this period, before succession is imminent, the generative CEO will strive to provide tailored developmental opportunities, including high-investment ones, to multiple executives.

The hypo-generative CEO, who is not mindful of eventual departure, provides few if any opportunities for executives to expand their capabilities beyond their current professional realms. This CEO, who might be talented in many ways, may see great benefit in developing executives for improved performance in their current roles but does not invest, or even contemplate investing, in broadening the skills and perspectives of top management team members.

The hyper-generative CEO, who is intent on the preparation and eventual elevation of one favored individual, will provide abundant developmental opportunities, including high-investment opportunities, to that one person. Other executives might be given opportunities to develop their in-role capabilities, but only one executive will be concertedly developed for bigger and broader responsibilities.

Finally, the anti-generative CEO, who is intent on preventing the availability of any ready successors, will not provide any top management team members with opportunities to develop beyond their current professional domains. At the extreme, this CEO might consciously or sub-consciously sabotage the professional enhancement of the most-promising executives.

CEO mindsets and management team structure

Beyond influencing a CEO’s actions directly related to the preparation of potential successors, a CEO’s generativity mindset also affects his or her behaviors in other domains of indirect importance to succession, perhaps most notably, the CEO’s choice about the desired degree of integration of the top management team.

At one extreme, the generative CEO, who is intent on preparing multiple candidates for eventual CEO readiness, will strive to provide forums for broadening the perspectives of individual executives and exposing them to fellow executives’ issues and contingencies.

The hyper-generative CEO, who is intent on identifying and developing one preferred candidate for eventual advancement, may also adopt a model of team integration, both as a way to assess executives in their dealings with each other and, then eventually, providing the favored candidate a forum for learning about the firm’s full array of issues and complexities.

The hypo-generative CEO, who is not oriented toward succession planning, will adopt a model that suits the firm’s strategic contingencies or other personal preferences, with little regard for whether team members develop firm-wide familiarity.

And at the other extreme, the anti-generative CEO, who is intent on preventing the availability of ready replacements, will go to lengths to minimize the degree to which the firm’s executives possess firm-wide understanding or exposure.

Impact of exiting CEO mindset on CEO succession outcomes

As a CEO’s tenure approaches its likely close, both the psychological and tangible implications of a CEO’s generativity mindset become all the more pronounced.

By this point, as discussed above, the generative CEO has undertaken various activities to assess and develop members of the top management team. This CEO’s generativity has led to the development of multiple viable candidates who are all well-known to the board, and the CEO now takes a backseat relative to the board, in essence saying, “Here are three strong candidates, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. You decide.” After the board’s decision, the incumbent will be available but not over-bearing in advising the successor, helping with orientation and introductions but not proselytizing. As such, a generative CEO is likely to oversee the appointment of a fully vetted and highly prepared insider.

The hypo-generative CEO, who has largely ignored succession planning, now faces a very anxious board. At this point, then, the board may rush to select the best available insider, who has received no special preparation or testing for the CEO position, or an outsider—in a classic case of a last-minute “crisis succession.”

At this late stage, the hyper-generative CEO has especially intense thoughts about maintaining control over the succession process through elevating his or her long-identified, hand-picked successor. By now, this executive has been carefully groomed, while no others have been at all groomed, so this ratification will tend to be straightforward for the board.

Finally, the anti-generative CEO, who has resisted the very idea of being replaced, and perhaps even sabotaged potential replacements, now faces the same anxious board as the hypo-generative CEO. The anti-generative CEO might lobby for yet more time to fulfill his or her “heroic mission.” Just as with a hypo-generative CEO, a crisis succession ensues, resulting in the expedient selection of the most satisfactory—but relatively unprepared—insider or, more likely, an outsider.

Implications for Post-Succession Performance

The outcomes of alternative CEO generativity mindsets have further implications for post-succession firm performance. Because such consequences entail a multi-step causal chain, we stop short of specifying concrete propositions. Still, these ultimate effects are sufficiently important to warrant attention.

Both hypo-generative CEOs and anti-generative CEOs tend to be replaced by unvetted successors, essentially the products of “crisis successions” (see also Richard Vancil’s formative work on CEO successions), who are either the best available insiders—but, again, with no special preparation or testing—or outsiders. If the former, the firm is in the hands of someone who knows the firm well but who may or may not have the requisite capabilities to be CEO. If the latter, an outsider, the firm is in the hands of someone who does not know the firm well, and who is thus susceptible to missteps.

Both generative and hyper-generative CEOs are replaced by prepared insiders but under different circumstances. Generative CEOs are mindful about developing multiple potential replacements, from whom their boards make their choice. These executives deeply understand their firms and their environments, but they have not been immersed in the long and deep indoctrination that occurs under hyper-generative CEOs. Thus, we anticipate they will be relatively open-minded and cognitively adaptive in the face of changes.

Hyper-generative CEOs, on the other hand, are replaced by their long-mentored disciples. As such, these new CEOs tend to adhere to the same logics and causal maps as their predecessors.

Succession Planning: The Board’s Role

Although some, perhaps many, boards lack much commitment to succession planning and are relatively passive bystanders, highly committed boards will encourage the CEO to think and behave like a generative CEO.

These normative expectations, even if reinforced by tangible practices and timetables, will have varying degrees of success in influencing CEOs. On the one hand, CEOs have incentives to honor their boards’ preferences; on the other hand, though, CEOs own generativity mindsets typically stem from deep personal strivings, which are not easily neutralized.

Among the archetypes, hypo-generative CEOs, who are essentially agnostic about succession planning, are expected to be relatively susceptible to their boards’ guidance in this domain. With no particularly resistant motives, they will make genuine efforts to approximate the behaviors of generative CEOs. Hyper-generative CEOs, who are committed to identifying and developing the one person who will be a suitable replacement, will try to broaden their attention to encompass more management team members, but this will be difficult for them. Anti-generative CEOs, however, will likely find ways to circumvent their boards’ urgings.

If the gap between the board’s expectations and the CEO’s succession-related behaviors becomes large enough, the board may sanction the CEO, possibly with the threat of heightened monitoring, pay penalties, or even dismissal. Such sanctions, even those short of dismissal, run the risk of exacerbating the strain between the board and the CEO. Although we do not envision CEOs being fired solely because of their inadequate preparation for departure, we readily picture CEOs being fired partly because of such deficiencies in combination with other shortfalls.

In sum, a board can complement the effects of its CEO’s generativity mindset on the succession planning process and eventual outcomes. Specifically, a board’s commitment to succession planning will influence the CEO’s succession-related behaviors, prompting the CEO to somewhat engage—partly genuinely, partly superficially—in the behaviors of generative CEOs. Given the strong evidence that such board commitment is far from universal, we hasten to specify a corollary: the less the board’s commitment to succession planning, the more that the CEO’s own generativity mindset will give rise to the respective outcomes portrayed above.

Conclusion

Despite calls for greater board involvement in succession planning, the motivations and behaviors of incumbent CEOs continue to greatly influence leadership transitions in public corporations.

Our framework highlights that a CEO’s generativity mindset is manifested years before succession is imminent, greatly shaping the contours of the eventual transition. During the main period of a CEO’s tenure, his or her generativity mindset propels various behaviors, including efforts to assess and develop top management team members for potential advancement, as well as the degree to which the CEO designs management team processes to encourage understanding of firm-wide issues and actors. In turn, when succession ultimately looms, a board may have multiple qualified candidates to select from, just one candidate, or none at all.

Our analysis posits that boards, through their own commitment to succession planning, can moderate these CEO tendencies, encouraging their CEOs to think and behave like generative leaders. Importantly, though, boards cannot completely countervail against their CEOs’ own personal preferences; indeed, depending on their CEO’s own mindset, a board might induce their CEO to behave a lot like or only a little like a generative CEO. Moreover, in those cases where boards lack much commitment to succession planning—which seems to be common—CEOs’ generativity mindsets overwhelmingly determine succession processes and outcomes.