October 1, 2019; New York Times

When the prison gates slam behind an inmate, he does not lose his human quality; his mind does not become closed to ideas; his intellect does not cease to feed on a free and open interchange of opinions; his yearning for self-respect does not end; nor is his quest for self-realization concluded. If anything, the needs for identity and self-respect are more compelling in the dehumanizing prison environment.

This quote from Justice Thurgood Marshall opens up a remarkable document from the American Library Association, Prisoners’ Right to Read, An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights. It was adopted in 2010 and amended in 2014 but based on the new report from PEN America, “a nonprofit organization that works to defend and celebrate free expression,” on the subject of access to books in prison, it appears that the country is still far from embracing its intent.

A prison in Ohio blocked an inmate from receiving a biology textbook over concerns that it contained nudity. In Colorado, prison officials rejected Barack Obama’s memoirs because they were “potentially detrimental to national security.” And a prison in New York tried to ban a book of maps of the moon, saying it could “present risks of escape.”

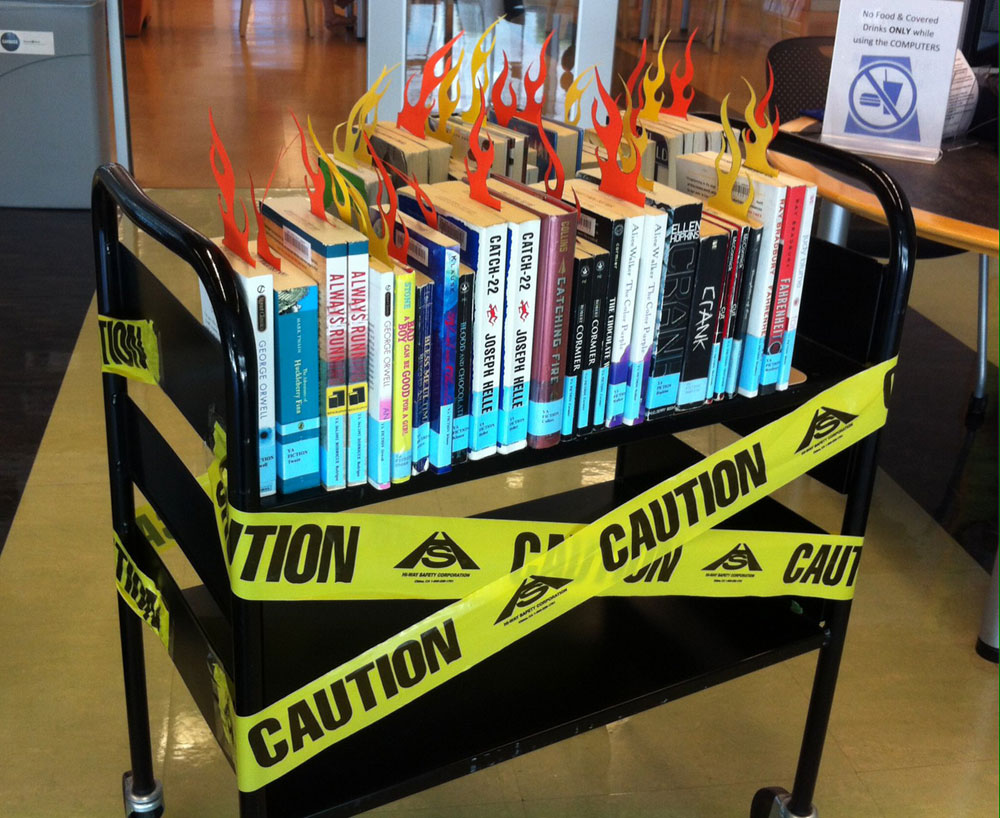

More than two million people are incarcerated across the country, and they are often subject to arbitrary bans that wall off entire genres in some cases and books in general in others. Yet, as PEN America writes, prisoners find future success in books: “The written word is a rare source of information, education, and recreation, and a window to the wider world.”

Book bans, though arbitrary, are predictable, in that they are often based on control over all else. Anything that might lead to unrest, like books on racism or the prison system itself, are filtered out for content. Disturbingly, these sweeping content bans often prohibit inmates from accessing books related to civil and human rights, under the guise that these books “advocate disruption of the prison’s social order.” (One such book is Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.)

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some prisons block all books because they are threat to security, others ban everything from the “self-help” genre. PEN America found that books containing content such as nudity, violence, “description of criminal activity,” or anti-authoritarian language were banned. Take away these general themes, and that leaves very few books that inmates can actually access.

For the most part, there is no appeal except through public outcry. Prison officials have broad authority to ban books, with no regulations or oversight to hold them accountable. And bans aren’t executed only at the institutional level; at the state level, they can become even more absurd:

- The state of Texas has an official banned list of over 10,000 banned books, and public reporting has indicated the list may now include over 15,000 titles. The statewide list reportedly includes such books as Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, and books on the Civil Rights Movement.

- Florida has a list of over 20,000 banned books. The nonprofit organization Books to Prisoners has noted that this list includes “Klingon dictionaries [and] a coloring book about chickens.”

- Kansas has had a list of over 7,000 banned books, including bestsellers like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. After the Human Rights Defense Center obtained and published the list in May 2019, the acting secretary at the Kansas Department of Corrections announced he would abolish the list and replace it with a new policy for reviewing obscene materials.

Going back to the ALA’s statement:

When free people, through judicial procedure, segregate some of their own, they incur the responsibility to provide humane treatment and essential rights. Among these is the right to read and to access information. The right to choose what to read is deeply important, and the suppression of ideas is fatal to a democratic society. The denial of intellectual freedom—the right to read, to write, and to think—diminishes the human spirit of those segregated from society.

—Sheela Nimishakavi and Ruth McCambridge