June 7, 2016, Sydney Morning Herald

The Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) has rebuked Australian “humanitarian and Mum to Many” Geraldine Cox, founder of Sunrise Cambodia, for the objectification and exploitation of the children in her care in fundraising campaigns. In other words, for producing “poverty porn.” The orphanage CEO, Lucy Perry, though a self-proclaimed “rule breaker,” defends the charity’s use of the images of “Pisey” and the other children.

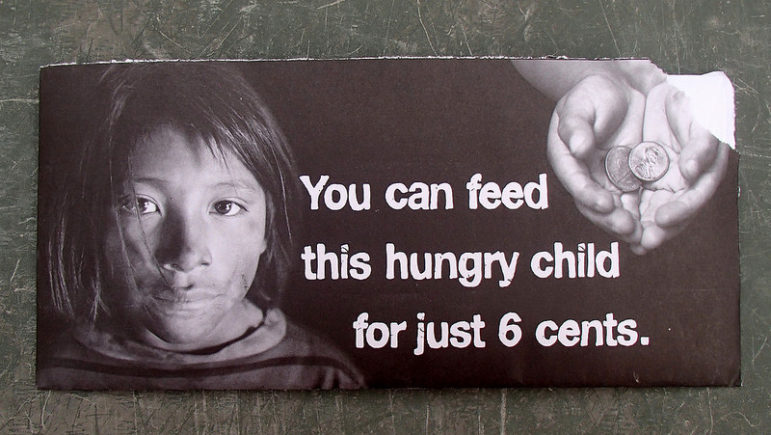

When does an appeal go too far? You be the judge. Is this “poverty porn”? This Sunrise Cambodia appeal raised more than $200,000 in Australia. Technically these are not “theft pictures,” as each child whose image was used was paid a fee. But does that add to the offense?

The reporter for this story is Lindsay Murdoch, a three-time winner of the Walkley Award, Australia’s top award for journalistic excellence. His opinion is apparent in the title of his article: “‘Poverty porn’ and ‘pity charity’ the dark underbelly of a Cambodia orphanage.” NPQ wrote in 2013 about this same issue of the exploitation of Cambodian children in “Pity Charity: When ‘Storytelling’ is Abuse.”

In 1981, Danish aid worker Jorgen Lissner wrote the seminal article on this subject called “Merchants of Misery”:

The starving child image is seen as unethical, because it comes dangerously close to being pornographic…it exhibits the human body and soul in all its nakedness, without any respect for the person involved.

CONCORD, the European confederation of relief and development NGOs, has a Code of Conduct on Images and Messages, though there is no binding agreement for organizations to follow the code.

Some of the world’s largest NGOs are still accused of showing their subjects’ most vulnerable moments. Consider this disturbing video from Save the Children that features a woman giving birth to an unresponsive baby. The mother moans and shakes. This distressing scene is followed by the text, “For a million newborns every year, their first day is also their last.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

When Save the Children was widely criticized for another television ad, this time depicting emaciated children, its spokeswoman defended the ad in an email to NPR:

Although we realize that these images may make people uncomfortable, we are committed to showing the reality of the situation and do not shy away from the issues vulnerable children around the world face. This particular advert was one of Save the Children’s most successful of all time in the UK in terms of motivating the public to support our work on food crises and chronic malnutrition around the world.

One problem with the obscenity of using “poverty porn” to raise money is that it works. These images do not aim to tell the truth; they sell a product. Besides its profitability, these images work as tourist brochures. As Lindsay Murdoch wrote in a previous article, “Orphanages are often run as businesses, the children being the assets.”

This 2011 UNICEF report indicates that the number of orphanages in Cambodia had increased by 75 percent in the previous six years. The government in Phnom Penh is cracking down on the orphanage industry:

Seventy-two per cent of about 10,000 children in Cambodia’s estimated 600 orphanages have a parent, though most are portrayed as orphans to capitalize on the goodwill of tourists and volunteers, including thousands of Australians, research shows. Up to 300 of these centers are operating illegally and flouting a push by government and UN agencies for children to be reunited with their parents. […] There is growing criticism across developing countries about “orphan tourism” and “volunteer tourism,” where thinly disguised businesses exploit tourists and volunteers.

Sunrise Cambodia is not under investigation, but as with Save the Children people and organizations are challenging them to change the visual conversation.

NPQ readers may remember other previous articles addressing the transgressions of “poverty porn” here, here, and here. There is even the issue of “ruin porn.”

“Poverty porn” is wrong because it misrepresents poverty. It leads to donations, but not to activism. It misrepresents the poor and denies them their dignity, and it deceives both the helper and the helped. In the end, the images lie about the poor, but not about the photographer and those paying the bill for the advertisement.—James Schaffer