Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during Mar/Apr 2016, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

AT ITS MOST SIMPLE, FUNDRAISING IS ABOUT ASKING for money from a person or an institution so that an organization or project can accomplish its work. The rate of exchange is clear: dollars invested; work done. It should be as direct as asking someone to pass you the salt when you are at the dinner table or hand you your coat when you are leaving a room, but it is not. Every time we ask for money, or are asked for money, there are generations of ghosts circling the room as we speak. The ghosts are attached to the issue of money—and all of the things we have attached to it.

Here’s a surprising thing: on an essential level, money doesn’t really exist. It’s a stand-in for goods and services. A kind of yellow Post-It note that says that the work you do has a certain worth within the community you are a part of, so you can exchange the value of your work for the value of someone else’s work.

Here is another surprising thing: all money comes from something free and in abundance: sunlight. Everything we buy and sell, every material good, including our bodies and everything that our bodies do or make, owes its origins to sunlight. Though the magic of photosynthesis, sunlight is turned into energy, which then moves through a cycle that eventually becomes a computer screen, a rubber tire, a box of chocolates, or the skull sweat of a new idea.

All money has its origins as that sunlight (however many generations removed), which then has value attached to it. Money represents a valuation that only has power once it is in relationship to something else. In other words, a $5 note is meaningless except for what it can do. And even then, it is meaningless unless it’s in relationship to something else: desire, longing, need, or strategy. At this point—this place where relationship comes in—is where money gets complicated.

Money is the same as the historical idea of race: a socially constructed concept that has evolved over time, not growing from biology but from the legacy of political and economic history, culture, family, and identity. It is not real in the sense of a piece of wood in your hands or the smell of a piece of chocolate, but something that is experienced through the systems and ideologies and behaviors that, too often in the case of race, end up as racism and white privilege. Money is just like that: A Post-It note or an electronic blip that doesn’t really exist except for the systems and ideologies that manage or organize it.

And, just like racism and white privilege, the systems and ideologies around money are what cause problems. And just like racism and white privilege, these systems and ideologies exist not only in the realm of infrastructures and public policies, they also exist within us. We become them and they become us.

From an early age, we are taught relationships to money through individual experience as well as through family experience and teaching, culture, community, and everything else that has an effect on who we are. Most of us who grew up with the dominant attitudes about money prevalent in the US have some kind of tension or anxiety in relation to money.

That tension or anxiety takes a lot of different forms: we feel that we don’t have enough money or we are afraid of not having enough. Or we are afraid of having too much or of wasting it. We worry about what we can afford to buy and struggle with wanting more than we have. We lie about money. We get into debt and don’t tell people about it. We help support our parents or grandparents or siblings or partners or friends—or even causes—and sometimes feel angry about doing so, wanting to keep our money for ourselves. We have inherited or are due to inherit and don’t tell anyone. Money often carries secrets that we are careful to not share. “Money” has a thousand faces that change based on our histories and our hungers.

Sometimes this tension is expressed as shame or guilt or bragging, but if you scratch below those expressions, you often end up with some form of fear. This tension and the underlying fear are part of how the idea of money gets its power. It thrives on that space between what we have and who we are right now and what we desire or long for or want to be. For each of us, these attitudes and fears are passed down, generation after generation. We know them sometimes as culture, sometimes as family ritual, and sometimes as survival.

Fundraising carries with it every kind of struggle or desire that has not been met. It carries with it everything we have learned about being poor, about being rich, about asking for what you need, about not having enough. These reactions are completely aligned with systems of privilege and oppression, with cultural differences related to individual versus collective responsibility, and with personal experiences of desire and power. All of these reactions—and the systems they are built on—can get in the way of people doing fundraising, particularly people who did not grow up with the privilege and power that our culture grants those who have money.

GIFT was created to empower and support communities of color to identify and create strategies that will increase the resources flowing into those communities. GIFT was created because resources are disproportionately accessible between white folks and folks of color. The fact that this happens at all is, among other things, about trauma—historical trauma.

What Is Trauma?

First, take out of your mind the idea that “trauma” only refers to situations involving extreme violence. Without diminishing the impact of situations involving extreme violence, it is true to say that trauma is pretty common. Trauma is not an event by itself, it describes what happens to us because of the event.

Trauma occurs when we are deeply frightened and are physically trapped or believe that we are trapped. We freeze into a feeling of helplessness. If there is no way to release the experience or to integrate it, that frozen experience can create a sense of collapse, of defeat, or of immobility. This sense of collapse or defeat or immobility is then triggered every time something occurs that reminds us of that first feeling of being trapped. When that is triggered, we react in a number of ways: with anger, with grief, with a sense of helplessness. This is the core of deeply held trauma. It’s as common as dirt. And it has informed our families for generations back—the ways in which our families survived or didn’t survive, how they parented us, modeled what it means to work and to love—all of these things are affected by generations of learning, of celebration, and of trauma.

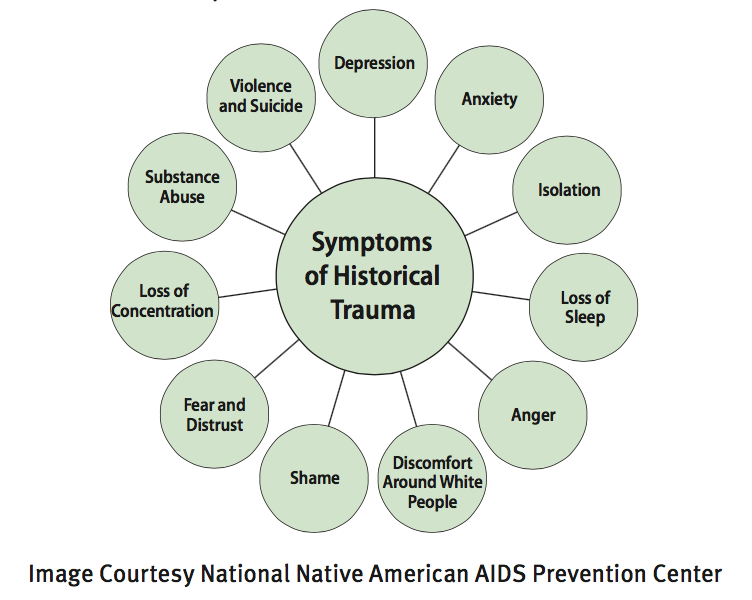

Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, Oglala Lakota, used the term “historical trauma” when she referred to the impact of generations of genocide of Native communities, of targeted violence through the form of loss of land, of language, of culture, and of lives. She linked this historical trauma to the high rates of physical, social, and cultural struggles experienced in Native communities today.

Dr. Joyce DeGruy Leary’s work uses the language of post-traumatic stress syndrome to talk about the intergenerational trauma of “post-traumatic slave syndrome,” meaning the systematic dehumanization of African slaves as the initial trauma that was then passed down through generation after generation of both perpetrator (white families) and the descendants of those enslaved. The institution of slavery became trauma when US nationhood refused to face and then heal from the extent of this history. Over generations, unresolved trauma becomes historical trauma. It mixes with and informs the individual experiences we have across our lifetimes, so that our actions and responses.

Trauma and Money

Our relationships to money are embedded with trauma and they are embedded with our history. Being a child and watching a parent stress about money, noticing the anxiety when the bills come through the door or when the creditors call on the phone, informs what money is to us as adults.

If we have experienced money used as control, as a way to maintain or take power, as a way to buy love, to prove yourself, to gain validation, to feel safe—these experiences inform how we show up around money today. And those individual childhood experiences are tied to larger collective histories: histories of doing without, histories of hunger, and histories of families who have experienced being an economic object, whether as worker or slave, with an autonomy forfeited for someone else’s profit.

Money lives through systems and relationships, both individually and within our family and community histories. Money is not real by itself, and the system of how money is saved or spent is part of the story of the United States. There is trauma embedded in money systems, the trauma of our families and communities and how they were able to survive.

When we fundraise, we are working within those money systems. These histories are part of how we think about resources, about having enough, about deserving to have our basic needs met, about how we ask for what we need and how we trust each other to provide. Thy are also part of how we envision our movements, our organizations, and our relationships to change

Ending this cycle and experience of trauma is about building resiliency. It’s about resourcing.

What Is Resourcing?

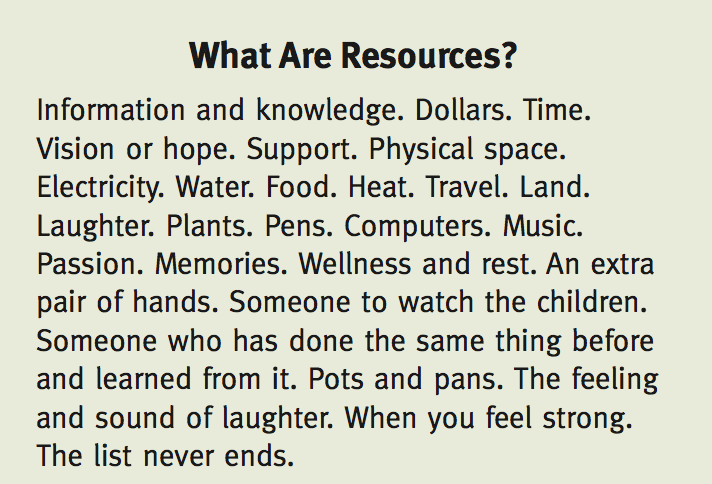

I use the term “resourcing” to encompass a way of thinking about getting what we need—beyond money. It’s actually a biological term and refers to how the body, through the nervous system, takes care of itself. Over time, resourcing has also come to mean how the collective body, or community, takes care of itself

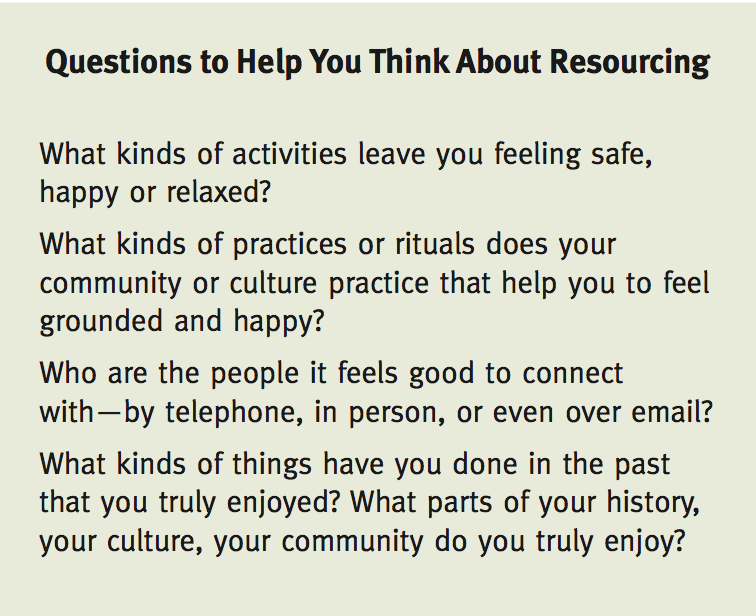

Resourcing is the ability to feel nurtured and calm within yourself or your community, to feel good. If trauma is a raging river, then resourcing is the ability to rest and regenerate, the quiet beach along the side. The greater the legacy of trauma, the harder it is to resource. This is as true for the individual body as it is for the greater community. Resourcing is a kind of safety net that is needed for the body to release trauma. Without resourcing, we cannot release and then move away from the trauma.

Individual resourcing is what happens when we are able to bring our awareness and to accept something that feels nurturing, safe, pleasurable. This can happen as sensation within the body—such as how strong my legs feel or how warm my heart feels. It can happen through experiencing something outside of my body: the sun on my face, the smell of garlic, the sound

of my daughter laughing. Or it can happen in response to an event: Eating a good meal with a group of people around a table and feeling that you are in exactly the right place. Working on a project or a campaign with others and feeling the hum. This sensing and feeling and being the “good” thing are resourcing, and we can’t heal or change without it.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The same works for communities. It’s important to have spaces in life where we are surrounded by people with shared histories, shared language, and shared ways of being alive. Communities cannot heal or change without the space or ability to resource. Resourcing is always a radical act of self-reclamation.

Resource Sharing and Fundraising

Resource sharing is about working from an organization or community’s strengths and finding what is needed, within those strengths, to build that organization or community. Resource sharing builds on a nervous-system analysis of resourcing, meaning that resourcing should nurture our work, and should contribute to the safety and sustainability of our communities. Resourcing is completely connected to healing from the trauma and struggles our communities carry. We cannot shift historical trauma without resourcing. Fundraising cannot be separate from that work of resourcing.

We live and work within a cash economy, where money is most often the standard of exchange. But the exchange of money through fundraising is not often envisioned in ways that resource our communities. Having money to pay for things is not the same as resourcing unless how that money comes through the door is tied to a feeling of nurturance, safety, and “goodness.”

So how do we resource our work rather than just get money for our work? And will we get enough to pay the bills?

Practices

When I first started to work on some of this material, I was mostly working for myself. It was a lot easier to think about these ideas: how to do them, what they looked like, and how they might support long-term change. Now that I am working as part of an organization, I see how hard working in this way is, how slow and incremental it is, how much the work must be thought of as for the long term. And for our nervous systems— meaning our ability to integrate new information so that we act or respond differently—slow is the best way. It’s the only way to guarantee that change is a lasting thing.

These practices are Offered as just that, practices that support thinking in 50-year chunks while also being open to the unexpected moments of transformation that surprise us.

First and first again: notice how your work is resourced.

In this work, in your organization, in your community, what feels good? What feels right? This gets called so many things in the nonprofit world—strengths-based approaches and so on. Forget all of that and make it personal. What feels good and right and how do you make it grow?

Here is the groovy thing about nervous systems, individual and collective: our bodies want to expand our ability to resource. By putting attention to resourcing—to the good and lovely and nurturing—we expand our ability to feel those things. Just by paying attention. Regularly.

Talk directly about money.

If you are involved with money—asking for money and needing money—then be as clear as possible about that money. Talk about it in the personal sense and in the political sense. Talk truthfully about the different experiences of money that are in the room. Practice seeing those different experiences as information, as resources you have to help you navigate the world of money.

Practice not setting up judgment scales based on who grew up with how much.

Don’t ignore class but instead, be deeply practical about it. Class differences exist in every community. They affect who is in what room and who is absent. They affect who had what kind of experience or support before they entered that room. Tell your stories. Learn from each other. Create a space where you can be angry or afraid or confused about anything related to money. And when you are angry or afraid or confused, notice what you have. Notice your resources, your strengths, the “good” things and then see what happens to your thinking. Keep reminding each other of what money is, of what affects the asking for it, support each other, and then go out and ask for more.

Then Think Beyond Money

Start with resourcing and end with resourcing. What will help you to build toward your work that isn’t about money? Create a community map. Start a map that is going to be ongoing as a practice. Keep an open and growing list of individuals and organizations that are a part of your community as you define it. Notice which of those listed you are interdependent with. Notice other relationships. Look for opportunities, including issues or problems or stuck places that want to be resolved. Notice who isn’t there and ask why.

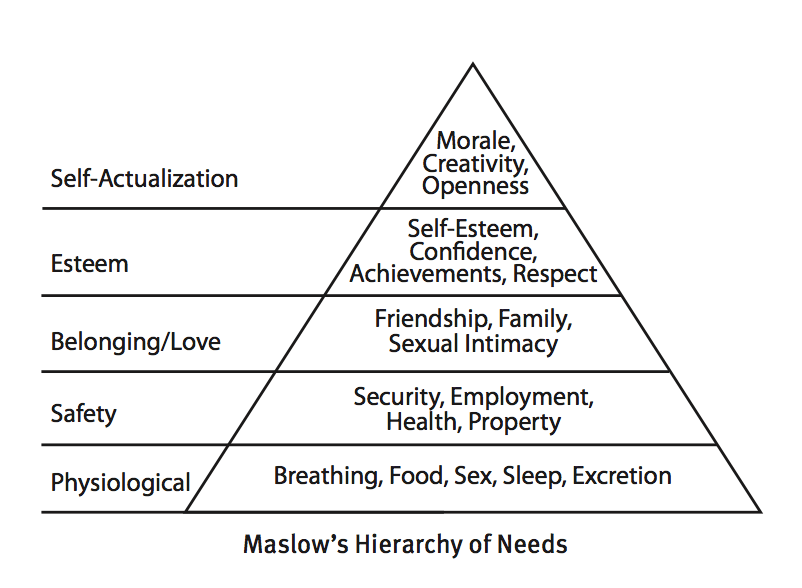

Figure out what your needs are and make them as explicit as possible. We have been trained to do a budget and a fundraising plan at the start of every fiscal year. Create a part of your budget that breaks down your needs into relationship categories rather than cash-exchange items. So, instead of rent you might list “a place where we can keep our stuff and have meetings,” and instead of salaries you might list the many ongoing tasks that need to be completed. And within needs, think as broadly as possible: the need for friendship and belonging, the need for a place to keep your stuff, the need for food. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see next page) is a useful tool for brainstorming needs. This is a kind of labor-and-material-goods audit that breaks your work down into concrete pieces.

Figure out what you have and how that can build.

Do the same kind of labor-and-material-goods audit with what you have and be as specific as possible. Don’t worry if this step feels like it’s not immediately about the work as it is currently defined. For example, one staff member might be an amazing gardener or be bilingual or a dancer. These are resources, gift, that might also be useful in surprising ways. Now, we put it all together to resource our work, from the center out.

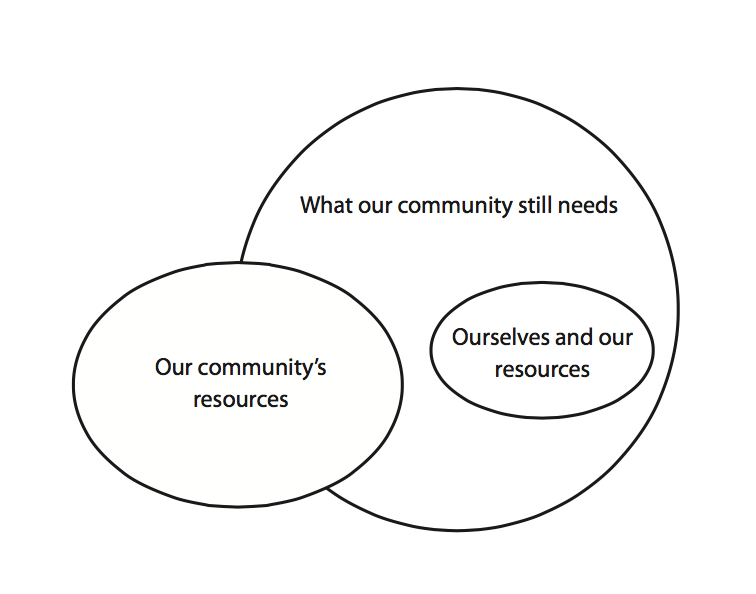

The first place we resource is with ourselves, whether we are talking about our individual or our collective bodies. Ask how you can build on what you have in order to meet what you need, including your own individual and collective sustainability. Next, we expand the circle to resource from our immediate community. Look at the community map you have created and match it against your needs. Ask how you can build from here. What relationships or connections can be deepened? What exchanges can be made? What barriers or problems can be cleared so that you have more access to the resources provided through community? And what can you give? How can you provide goods or services to your community beyond what you are already doing?

When this is all done, look at the unmet needs. This is where money is going to come in, but in bringing money into the equation, continue to be as direct and transparent as possible.

Then repeat this whole practice again and again and again, continually coming back to resourcing, particularly when things feel hard or you feel stuck or overwhelmed. This is precisely the moment when resourcing can help us to shift and transform. Each time we do it, it gets a bit stronger and easier the next time. With attention, our ability to resource in ways that are good and sustainable will only grow—from the individual nervous system and out to communities.

Three Seconds and a Lifetime of Trusting

Each cell in our body only has three seconds of oxygen at any point. Part of our existence at the cellular level is trusting that the resource of oxygen will be there when we need it. These seconds and a lifetime of trusting. That’s what this work is about.

We know how to keep things the same, caught up with a cash economy that starts with the free resource of sunlight and turns it into a system and practice that is not free. We know that everything our communities have experienced and known affects how and if we can resource ourselves. We know how to survive because we are here today. It is deeply important to be grateful for every single thing we have learned and done in order to survive. Without it, we wouldn’t be here and ready to change.

But surviving is not the same as liberation, as having access to all of the goodness that exists through connection, through the space to feel the sunlight on our skins, the time to notice our children.

Moving beyond survival is slow and deeply intentional work. Fundraising as we know it maintains the status quo, only redistributing some of the money to some of the places where it’s been lacking. Resourcing is about transformation.

Three seconds of oxygen. Now, breathe again.

Susan Raffo lives in Minneapolis, MN with a body that carries the ancestry of both colonized and colonizer. She is a writer, bodyworker community organizer and, as part of a job share, is one half of the Executive Director of the PFund Foundation. Thinking for this piece has to be shared with Sarah Abbott, Coya Hope Artichoker, Kate Eubank, Heather Hackman, Lex Horan, Thea Lee, David Nicholson, Cara Page, and Jessica Rosenberg to name a few.