July 30, 2012; Source: Remapping Debate

On Craig Gurian’s Remapping Debate site, Heather Rogers reports on the gap between the progress that European nations seem to be making toward enacting a “Robin Hood tax” (covered in the NPQ Newswire here and here) and the near comatose response to such a proposal in the U.S. The Robin Hood tax is a financial transactions tax (FTT)—a small fee placed on stock, bond, or derivatives transactions. While Rogers writes that some of the European proposals call for a tax as high at 0.1 percent, we recall most discussion at the G20 meeting in 2010 focusing on a 0.05 percent FTT. The tax would possibly do three things: (1) generate substantial new funding for anti-poverty programs; (2) slow down the speculative high-frequency trading that Rogers and others suggest destabilizes markets; and (3) get firms in the financial sector to pay something closer to their fair share of taxes.

Despite Tim Geithner’s less than enthusiastic response to the idea, particularly as it was being pitched by some Occupy Wall Street types, the Robin Hood tax isn’t a hare-brained notion cooked up by Zuccotti Park campers to stick it to JPMorgan Chase and Citicorp. Among the enthusiastic supporters of a Robin Hood tax are economists Joseph Stiglitz and Jeffrey Sachs, as well as Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Baker’s own FTT proposal calls for a tax on stock transactions at 0.05 percent and on bond and derivative transactions at 0.01 percent. In terms of potential congressional movement in favor of a Robin Hood tax, there’s not much. Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) and Rep. Pete DeFazio (D-Ore.) introduced a bill in 2011 that would establish an FTT at a 0.03 percent tax rate. DeFazio has described the financial markets as a “very lightly regulated casino…[that has] has very little to do with raising capital to support productive enterprise.” But as far as we know, there’s no evidence of a flock of Democrats joining Harkin and DeFazio.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

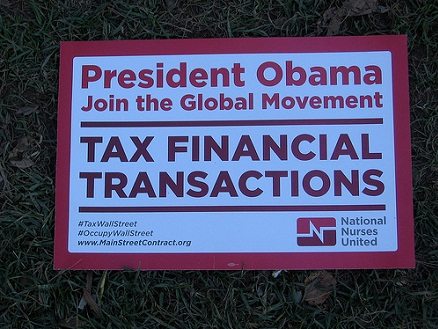

A Robin Hood tax campaign has nonetheless arisen with support from some significant labor and progressive constituencies usually friendly with the Democratic Party, including the American Postal Workers Union, Greenpeace, Jobs with Justice, National Nurses United, the National Organization for Women, Oxfam America, and Public Citizen. Famous people identified as supporting the tax include Bill Gates, David Stockman (budget advisor to President Reagan), John Bogle (retired founder and CEO of Vanguard), Paul Volcker, Warren Buffett, Paul Krugman, and Mark Cuban (owner of the Dallas Mavericks). But no dice. Most Democrats aren’t even murmuring support for the idea—including President Obama.

Rogers suggests, and we agree, “that the torpor of most Democrats is a function of the influence wielded by the financial sector.” It isn’t just that the Democrats do not want to tick off Wall Street. Despite some vocal criticisms of the banks, the Democrats are well supported, sometimes quietly, by financial institutions. A recent Charlotte Observer article, for example, notes the extensive interrelationships between the Bank of America and the Democratic Party in the run-up to the national convention in Charlotte. Although the Democrats have foresworn corporate contributions to the convention, they have structured mechanisms for the Charlotte-based bank to contribute millions to nonprofits working with the convention. Two community banks and a credit union in Charlotte received $4.5 million in party funds as the Democrats showcased their support for small and minority-owned banks—but in a demonstration of mutual support, the Democratic Convention Committee quietly deposited nearly four times as much with the Bank of America.

The Robin Hood tax could generate billions in desperately needed government funding for social programs. Even center-right governments in Europe are moving toward enacting an FTT. It’s just not happening here.—Rick Cohen