Kim Klein’s writing and training on fundraising as part and parcel of social justice work is a gift to community-based and progressive groups everywhere, and NPQ is proud to present this two-part article over the next several days. This article, first published online on February 11, 2016, is adapted from the 7th edition of Fundraising for Social Change for the Grassroots Fundraising Journal.

The financial payoff in fundraising is when you regularly receive large gifts from an ever-increasing number of your donors. To build a major donor program, no matter the size of the organization, a majority of staff, board and volunteers must feel comfortable asking people for money in person. For many people, that comfort starts with being able to ask someone to purchase a $20 ticket to a benefit event or for $35 to become a member.

Some people never move past that level of comfort. But if an organization is to grow and thrive, a critical mass of board, volunteers and staff must be able to ask for much larger gifts—$500, $5,000, $50,000, and even more.

A person doesn’t have to like asking for money to be able to do it. Some of the most successful fundraisers I know have confessed that they always feel anxious when asking for money. But they do it anyway. Sometimes their nervousness makes them prepare more thoroughly for the solicitation and feel even better about themselves and their group after they complete it.

Once it becomes part of the organizational culture to always have a cross-section of board, staff and volunteers who ask for large gifts, you then need a system for identifying prospects and regularly soliciting such gifts. That system is a major gifts program.

Before beginning a major gifts program, your organization must make a number of decisions: how much money it wishes to raise from large gifts, the minimum amount that will constitute a major gift (I recommend $500 but many organizations start at $250), and how many gifts of what size are needed. In addition, you must decide what, if any, tangible benefits donors will receive for their gifts and what materials will be needed for the solicitors. Finally, a core group of volunteers must be trained to ask for the gifts.

Getting Over My Own Fear of Asking

Over the decades that I have been in fundraising, I have asked a few thousand people for gifts of all sizes, including three requests for $1,000,000. (Of those three, one person gave the whole amount, one gave $300,000, and one told me she would rather fall face first in her own vomit than give our organization money—but that’s a long story.) My feelings about asking have evolved from “Do I have to?” to “This is exciting.” To this day, sometimes I think, “Do I have to?” or “Can’t someone else take a turn?”

Even though I tell people not to take rejection personally, I have to admit that on bad days I sometimes do take it personally—and I have to work to let it go. In my experience, no one ever arrives at a place of total peace with asking. But with familiarity, we have more of those peaceful times and fewer times of anxiety, frustration even resentment because of this work. Often my feelings of peace are enhanced by euphoria after being told, “Yes, I’ll do it,” gratitude for someone’s extraordinary generosity, or pride in the accomplishments of the organization. Some donors make it easy to ask because they are so moved by the work or are warm, caring people. Sometimes I am just flooded with relief when the donor said yes right away or the donor wasn’t at work when I called!

Feelings are not facts. They come and go, and they are often not very logical. I have found the best way to be the most comfortable with asking is to feel confident that I have made a significant gift, not just of my time, but also of my own money, before asking for a major gift. When I know I am asking a prospect to join me by making their own gift, I stand on firm ground.

Setting a Goal

The first step in seeking major gifts is to decide how much money you want to raise from major donors. This amount will be related to the overall amount you want to raise from all your individual donors and can be partly determined on the basis of the following information.

Over the years, fundraisers have observed that a healthy organization’s gifts tend to come in as follows:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- 10 percent of the donors give 60 percent of the income.

- 20 percent of the donors give 20 percent of the income.

- 70 percent of the donors give 20 percent of the income.

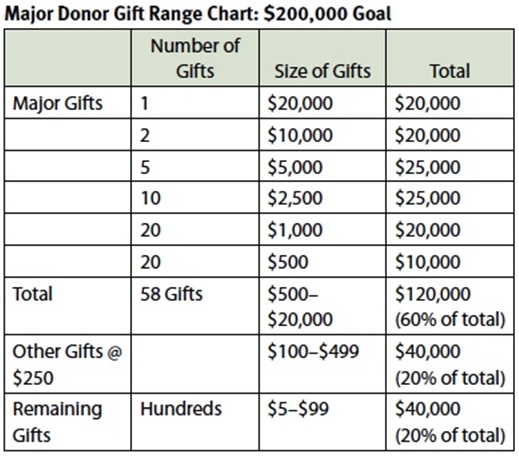

In other words, the majority of your gifts will be small, but the bulk of your income will come from a few large donations. Given that pattern, it is possible to project for any fundraising goal how many gifts of each size you should seek and how many prospects you will need to ask to get each gift.

It is easy to see that if your organization must raise $100,000 from grassroots fundraising, you should plan to raise $60,000 (60 percent) from major gifts, mostly solicited personally; $20,000 (20 percent) from habitual donors, mostly solicited through phone, mail or email, as well as regular special events; and $20,000 from people giving for the first or second time, solicited from mail and online appeals, speaking engagements, special events, product sales, and the like.

If you have 500 donors, expect that about 50 of them will be major donors, over 100 will be habitual donors, and about 350 will be donors who will give to your special event or in response to a crowdfunding campaign but for whom your organization is not a high priority. The lowest major gift you request should be an amount that is higher than most of your donors give but one that most employed people can afford, especially if allowed to pledge. Even some low-income people can afford $60 a month, which brings being a major donor into the realm of possibility for all people close to your organization.

Some organizations try to avoid setting goals. Their feeling is that they will raise as much as they can from as many people as they can. This doesn’t work. Prospects are going to ask how much you need; if this answer is, “As much as we can get,” your agency will not sound well run. If prospects think you will simply spend whatever you have, they will give less than they can afford, or nothing. Further, without a goal there is no way to measure how well the organization is doing compared to its plans. Just as no one would agree to build a house based on the instructions, “Make it as big as it needs to be,” organizations can’t be built on the premise, “We will raise whatever we can.”

Deciding How Many Gifts and What Size

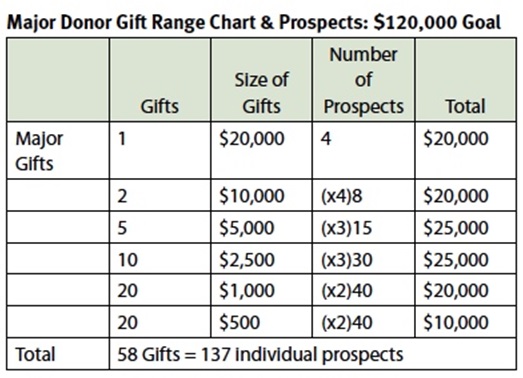

It would be great if you could say, “Well, we need $40,000 from 10 percent of our donors, so that will mean 200 people giving $200 each.” But 200 people will not all behave the same way—some will give more, most will give less. Given this reality, fundraisers have made a second observation: For the money needed annually from individual donors, you need one gift equal to 10 percent or more of the goal, two gifts equal to 10 percent (5 percent each) or more of the goal, and four to six gifts providing the next 10 percent of the goal. The remaining gifts needed are determined in decreasing size of gift with increasing numbers of gifts. Let’s imagine an organization that needs to raise $200,000 from a wide variety of individual donor strategies. Using the pattern just outlined, $120,000 will be raised from gifts over $500. Their gift range chart will look something like the example shown here.

The Gift Range Chart is like a map drawn on a napkin—it is not to scale, and few campaigns wind up having every gift fit exactly into every category. But it is an important planning document and is helpful for testing the reality of a goal. For example, if your goal is to raise $100,000 but the biggest gift you can imagine getting is $500, then you will probably have to lower your goal. The chart is also helpful for board members and other volunteer solicitors who may have difficulty imagining raising $100,000 but can imagine thirty people giving $250 each.

How Many People to Ask

Every fundraising strategy, presuming it is done properly, has an expected rate of response. For major gifts, the expected response rate is that 50 percent of prospects will say yes to making a gift when the gift is requested by someone who knows the potential donor, knows that that prospect believes in the cause, and feels reasonably certain that the prospect could give the amount of money being asked. However, if the prospect does say yes, there is a further 50 percent chance that he or she will give less than the amount requested. With this understanding, for every gift you seek through personal solicitation, particularly at the upper reaches of the chart, you will need at least four prospects—two will say yes and two will say no. Of the two who say yes, one will give a lesser amount than requested. Because the higher gifts prospects who say yes but give less than asked for end up filling in the number of gifts needed in the middle and bottom ranges of the chart, you will need only two or three new prospects for every gift needed in those ranges. Overall, look for about three times as many prospects as gifts needed. For the $200,000 goal, then, the top portion of the chart would be expanded to include numbers of prospects.

In other words, when someone from your organization asks four qualified people for $20,000, two will say no, one will give $20,000, and one will give less than $20,000. As you go down the chart, you are filling in the next layer with the smaller gifts from the higher layer, so you don’t need to identify quite as many prospects for the gifts you need in the lower layers of the chart.

This article was published in its original form on January 21st, 2016, at the Grassroots Institute for Fundraising Training’s blog. Click here for Part II!