Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during Sep/Oct 2016, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

HAVE YOU EVER BEEN FOCUSED on managing an event, running a major gift campaign, writing multiple grant proposals and reports, generating a year-end appeal—or busy juggling all of these responsibilities and more—to raise the funding you need for the current or next fiscal year? The vast majority of development directors, executive directors, and other fundraising staff members with whom I’ve worked as a consultant over the past five years fit this description.

If you, like them, engage in any fundraising planning, chances are you focus on the upcoming fiscal or calendar year. If you are in strategic planning mode, you might set three- to five-year income projections. But have you ever thought about planning to position your organization for fundraising success decades from now?

I invite you to consider, if only for the time it takes you to read this article, why it’s important to think of ways that your organization can set itself up for greater long-term fundraising stability.

Unfortunately, the problems that social justice organizations address—racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, anti-immigrant policies, environmental degradation, and economic inequality—will not disappear soon. These problems may mutate in ways that will require nimble, strategic and smart organizations that are well-funded by a solid base of donors who can help both financially and politically.

What will your community of supporters look like in two decades?

We’re living through a time of seismic demographic shift that will continue for the next 30 years. Social justice organizations that ignore or resist these changes run the serious risk of not only losing supporters (to natural attrition and death), but of not replacing those donors with new contributors, missing important opportunities to build movements for equity and justice.

This article lays out big picture data from the 2010 census and other sources that show how the U.S. population is quickly becoming much more diverse than it ever has been, which has serious implications for fundraising and organizing.

Of course, progressive, forward-thinking organizations manifest their values by creating and growing donor bases that reflect racial, gender, sexual orientation and age diversity. They recognize this is necessary to build vibrant, relevant and sustainable social movements that engage the people directly impacted by the organizations’ missions.

Many nonprofits focused on people of color, LGBTQ communities and women (and those working at the intersections of these groups) have long recognized the need to “support our own,” and have generated funding and political power from within their communities.

If your organization is not already in this camp (and even if you are), I hope the data in this article will provoke you to think about what your group can do now to be ahead of the curve, rather than racing to catch up—not only for financial reasons, but for movement-building reasons.

Remember that 70 percent of adults in the U.S. contribute to nonprofits. If we want to maintain if not increase that percentage in the future, we’ll need to do all we can now and in the years ahead to build donor bases that reflect the changing mosaic of the U.S. population.

People of Color Will Be the Majority

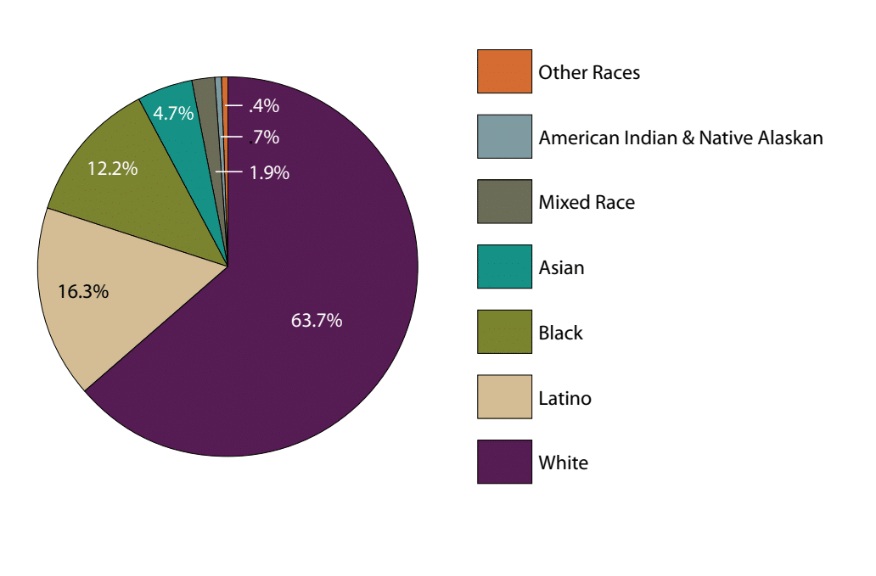

The 2010 census revealed the following racial/ethnic composition of the U.S. population:

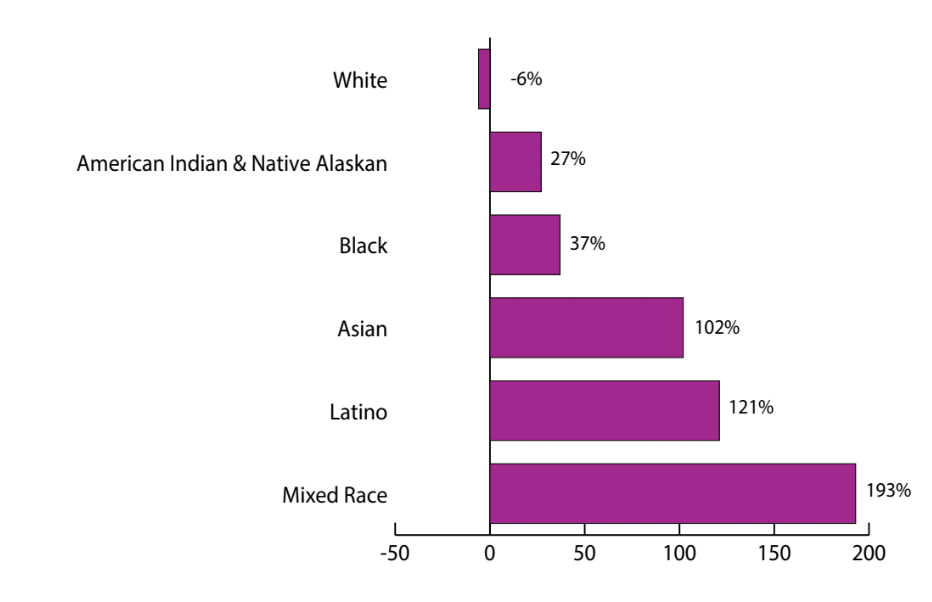

Between 2000 and 2010, the white population grew by just 1.2 percent, while the population of people of color grew by 29 percent. During that same decade, the numbers of people who self-identify as multiracial rose by nearly 33 percent.1 Now consider the projected growth of different racial/ethnic groups in the current and next three decades:

Projected U.S. Population Growth by Race: 2010-2050

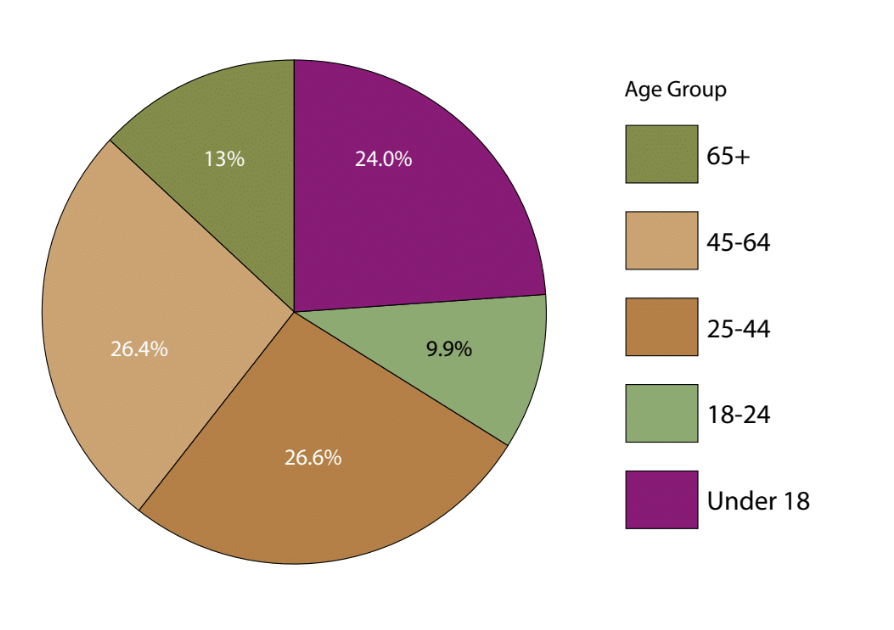

If these growth rates prove accurate, the more than 200-year period of the white population’s majority in the U.S. will come to an end in the foreseeable future. No single racial group will be a majority by sometime after 2040. Looking at demographic data through the lenses of both race and age, we see some big contrasts. The 2010 census showed that the U.S. population fell into the following age groups:

Baby Boomers and seniors (everyone born before 1965) made up 39 percent of U.S. residents, while Gen Xers (people born between 1965-1979), Millennials (those born between 1980-2000), and children constituted 61 percent. So in 2010, younger people already represented a significant majority of the population.

The Baby Boomer generation (people born between 1946- 1964) and seniors (those born before 1946) are more than 70 percent white. Within those generations, African Americans are the largest “minority” group. Millennials, younger Gen Xers and their children (everyone born after 1975) are more than 40 percent people of color, with Latinxs being the largest “minority” population. 2

The trend of younger generations being more racially diverse is only going to intensify. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of white children shrunk in 46 states and the nation as a whole. During the same period, the population of Latinx children grew in all 50 states; the number of Asian American children decreased in only two states, and mixed-race child populations grew in all states. 3

2011 was the first year in which the majority of babies born in the U.S. were not white. Latinx births, at more than one quarter of all births that year, were the highest of any racial/ethnic group.4

Minority White ‘Tipping Points’ for Different Age Groups

| Age Group | Year when People of Color Become the Majority |

| Under 18 | 2018 |

| 18-29 | 2027 |

| 30-39 | 2033 |

| 40-49 | 2041 |

This table indicates that in about a year, whites will be less than 50 percent of U.S. residents under the age of 18. In each of the following “tipping-point” years, whites will be less than one-half of that age-group and those younger. The Census Bureau projects that Latinxs will make up about one-quarter of the population in each “tipping point” year.

Because the population of younger people is much more racially and ethnically diverse than older residents, the complexion of the United States will change significantly as the largely white Baby Boom and senior generations pass away and as more children of color and mixed-race people are born.

Who Will Be Working and Retiring (and Donating) in the Next 15 Years?

The composition of the labor force is of particular interest to nonprofit fundraisers. Since most people make contributions from their income, usually generated from a job, the size and characteristics of people in the age group demographers consider the labor force (18-64) are important to keep in mind. Of course, not everyone in this age cohort will be working, have a steady income, or donate to nonprofits. Nevertheless, it’s helpful to keep an eye on who constitutes this large age category.

Between 2010 and 2030, the number of 18- to 64-year-old whites is projected to decrease by 15 million. During that same period, the number of Latinxs in that age group should grow by 17 million. Asian Americans and African Americans in that age group are expected to increase by 4 million and by 3 million respectively.

Whites will still constitute a majority of 18- to 64-year-olds between 2010 and 2030, but their share is projected to decrease from 64 percent in 2010 to 54 percent in 2030. And looking further into the future, people of color will become a much larger share of the labor force because of their large youth populations: By 2030, 54 percent of Latinxs, Asian Americans and mixed-race individuals are projected to be under the age of 40.6 Consequently, the majority of the labor-force-age population sometime after 2030 will be people of color.

Between 2010 and 2030, the senior population (65+) is projected to grow by 81 percent as the largely white Baby Boom generation continues to age.7 In 2015, Baby Boomers and seniors accounted for almost 70 percent of giving from individuals.8 Since we know that more than 70 percent of Baby Boomers and seniors are white, the majority of donors in 2015 were white.

Members of these older generations, if not already retired, will retire in the near future. While they will most likely continue to contribute to nonprofits, they may have lower incomes and not be able to give as generously as they did when they were working. If a large part of your donor base consists of Baby Boomers or seniors, you may experience during the coming decade a steady drop in both the number of donors in these generations (due to their deaths) as well as the amounts they’re contributing (because of lower income).

As younger people of color replace the Baby Boom and Senior generations in the labor force and in political and institutional leadership, significant questions for nonprofit fundraisers arise:

- Will the more diverse GenX and Millennial generations and their children take the baton from their elders and continue to give as widely and generously to nonprofit organizations?

- What are you doing now to encourage younger donors, especially young people of color, to invest in the social, environmental and economic changes that you’re working on?

Diversity Spreading Across the Country

I live in downtown Los Angeles, so I see the future of the country every time I walk down the street. Hard-hatted Central American construction workers and pony-tailed blonde matrons walk alongside Korean grandmothers and Mexican American teens wearing parochial school uniforms. Young Black mothers bouncing babies on their knees sit beside tattooed Armenian American hipsters at my neighborhood Starbucks.

These of you who live and work in areas of the country where the demographic complexion is still largely white may be thinking, “Racial diversity may be the wave of the future, but it’s not going to affect where I am for a long time.” You might soon be surprised by the swiftness with which your community, region and state changes.

Rapidly growing racial and ethnic diversity is not just manifesting in more cosmopolitan cities and states—it’s spreading to almost every region of the country

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

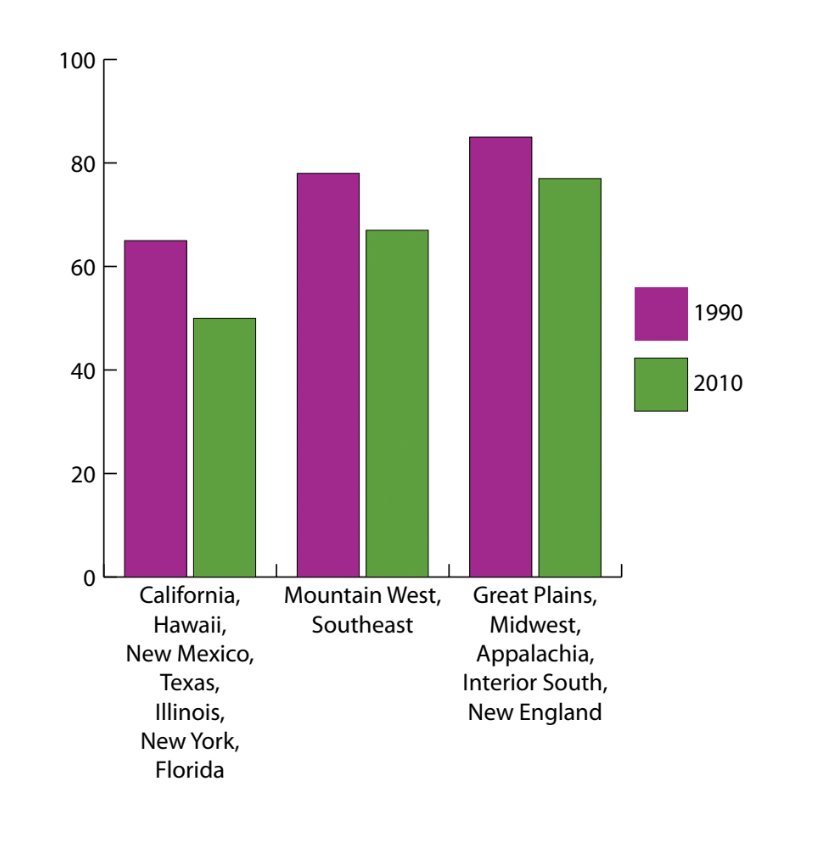

In the 1990s, the most racially diverse states (California, Hawaii, New Mexico, Texas, Illinois, New York, and Florida) were 65 percent white. By 2010, whites constituted 50 percent (or less) of people in those states. Similarly, in 1990, 78 percent of people in the Mountain West and Southeast were white; in 2010, that figure dropped to 67 percent. And in the Great Plains, Midwest, Appalachia, interior South and New England, 85 percent of the population was white in 1990, but in 2010, that figure dropped to 77 percent.9

Rapidly growing Latinx, Asian and multiracial populations are moving from the most diverse areas of the U.S. to almost all parts of the nation. Historically, Latinxs have concentrated in California, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Miami and New York City. Between 2000 and 2010, however, Latinxs settled throughout the country, with significant growth (at least 86 percent) throughout the South, Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states.

Keep in mind that “Latinx” is an umbrella term covering people of different national origins, with varied histories in the U.S. and uneven dispersal in the country. Two-thirds of Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants (who constitute about two thirds of Latinxs in the U.S.), for example, live in California, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado.10 Puerto Ricans are largely concentrated in the New York City metro area. Rapidly growing Salvadoran and Guatemalan populations are more evenly spread between the East and West Coasts.

Like Latinxs, Asian Americans are people of different national origins, immigration histories, and geographic distribution. Since the beginning of Asian immigration to the U.S. in the 19th century, most Asians have lived in metropolitan areas on the West Coast and in Hawai’i. Nearly half of Asian Americans lived in West Coast states, Hawai’i, New York, and Illinois between 2000 and 2010, but Asian populations rapidly grew (at least by 70 percent) in Southern, Midwestern and Northeastern states.11 Growth of the South Asian American population is noteworthy in areas of the country where Asians historically have not lived in large numbers, like Atlanta, Georgia and Raleigh, North Carolina.

In 1900, 90 percent of African Americans lived in the South. But during the early 20th Century, Blacks moved in vast numbers to Northern and Western states as part of the “Great Migration.” By 1970, a little more than half of African Americans lived in Southern states. But during the last four decades, Blacks have been migrating to the South in significant numbers. Since the 1990s, Southern states have been gaining African American migrants from all other regions of the country, most significantly from New York, Illinois, Michigan and California, in part because of rising housing costs and displacement due to gentrification. In fact, the 2010 census revealed that for the first time, these states reflected absolute losses in African Americans.12

This movement to the South consists of mainly younger, college-educated and Baby Boomer-age African Americans. Black college graduates have settled mainly in Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina. And demographers project that a surge of African American retirees will settle in the South during the coming two decades. The beginning of that wave is already evident by increases of African Americans 55 and older in Georgia, Texas and North Carolina.13

Although large areas of the South are becoming much more multiracial, African Americans will remain the largest “minority” group due to the migration of Blacks to Southern states.14

The majority of people of color (67 percent of Latinxs, 79 percent of Asians, and 64 percent of African Americans) still reside in major metropolitan areas with more than one million residents.15 But that doesn’t mean that most people of color concentrate in inner cities. Suburbs, which historically have been largely white, are becoming much more polychromatic. More people of color in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas now live in the suburbs than in the core city.16 In 2010, more African Americans lived in suburbs than in the inner cities of the biggest metropolitan areas.

Despite all of these dynamic changes, diversity is manifesting more slowly in some regions. In 2010, nearly half of the nation’s rural and small metropolitan counties were still more than 90 percent white, even though many rural counties are losing white residents and gaining people of color.

Millennials Support Social Justice Issues

In recent years, a wealth of research has focused on the Millennial generation. The Millennial Impact Project, an ongoing multi-year research project centered on this generation’s involvement with causes, for instance, has issued a series of reports on Millennials as donors and volunteers. The Project found that in 2010, 93 percent of Millennials contributed to nonprofits.17

Research on Millennials reveals both encouragement and challenges for social justice nonprofit fundraisers. On the positive side, Millennials have been the most liberal of any living generation, and the only one in which liberals are not significantly outnumbered by conservatives.18 In a 2014 survey, 31 percent of Millennials say their political views are liberal, 39 percent are moderate, and 26 percent are conservative.19

Millennial’s political perspectives, however, vary significantly across racial and ethnic lines. Although the percentage of Millennials who identify as Independent is fairly consistent across race, nearly twice as many Millennials of color identify as Democrats than white Millennials. And the opposite is true on the Republican side. More than twice as many white Millennials identify as Republicans than do Millennials of color

Millennials are at the forefront of support for same-sex marriage and the legalization of marijuana, and they hold more progressive positions than older generations on immigration reform. And they are far more likely than older age cohorts to support an expanded role for government.20

So the positive sign for progressive organizations is that, at least in a broad sense, Millennials (and Millennials of color in particular) are likely to be sympathetic to if not in agreement with their social justice missions.

Another positive sign for nonprofit fundraising is that older Millennials (those born between 1980-1988) are the best-educated sub-generational group in U.S. history; one-third hold at least a four-year college degree. This is significant because now more than ever in U.S. history higher education is vital to economic stability and success.21 Millennials are projected to comprise 50 percent of the U.S. workforce by 2020. That percentage will only increase as Baby Boomers retire.22

Education and volume in the labor force, however, do not necessarily translate into economic stability for Millennials. College graduates carry record levels of student debt: Two-thirds of recent graduates have outstanding loans, and the average amount they owe is $27,000. Twenty years ago, only half of graduates had to repay loans, and their average debt was $15,000.23

Many Millennials entered the job market during the Great Recession (2007-2009) and are establishing their careers during the longest period of economic sluggishness in modern American history. During this same period, income and wealth gaps have widened dramatically. Millennials have lower levels of wealth and personal income than their two immediate predecessor generations (Gen Xers and Boomers) had at the same stage of their lives. 24

So, although Millennials may believe in the change that social justice organizations are trying to achieve, they may not yet be in a position to replace the generosity of the aging Baby Boom and senior generations.

What Now?

People of color becoming a majority and the rise of the Millennial generation do not translate into equitable distribution of wealth, income and resources. Social justice advocates know all too well the gargantuan income and wealth gaps in the U.S.

On average, about half of total annual giving by individuals comes from households with an annual income of more than $200,000 or assets greater than $1 million. In some years, this figure could be as much as two-thirds. 25 How many families of color and Millennials are in that group?

A recent study concluded that if average Black family wealth continues to grow at the same pace it has over the past three decades, it would take Black families 228 years to amass the same amount of wealth white families have today. For the average Latinx family, it would take 84 years to generate the same amount of wealth white families have today.26

More research and analysis are needed to examine the intersection of racial/ethnic demographic changes and income/wealth inequality.

As I indicated at the beginning of this article, my intention is to encourage thought about how demographic changes will impact your organization’s fundraising efforts and what you can do now to plan for those changes.

Here are some questions to guide discussions with your colleagues:

Do we know the demographic profile of our donor base?

If you don’t, now is a good time to try to get that information through donor surveys and other means. That information will provide a baseline to determine how your organization’s donor base is representative, if at all, of the people impacted by the issues your organization addresses. (See “Using Surveys to Strengthen Donor Relationships” by Stephanie Roth in the Journal archive, May-June 2013, v32 n3.)

If we know the racial and age demographics of our donors, do they reflect the geographic region in which our organization operates or the communities impacted by our work?

Most of the nation is quickly becoming more racially diverse, with large metropolitan areas leading the way. Organizations in metro areas should be thinking sooner rather than later about diversifying their donor bases compared to those located in rural or smaller metropolitan areas. And organizations in the South should be building, if they haven’t already, a base of African American donors.

How many of our donors are Millennials?

Millennials will soon be the majority of American workers. While Millennials may not yet be able to give significant annual gift, over time they will be a dominant force in U.S. culture, if only by sheer force of numbers. Are you reaching members of this generation with compelling reasons why they should support your cause? See the Millennial Impact Project (themillennialimpact.com) for guidance on how to best reach and engage Millennial donors, such as providing specific stories and statistics on how their donations are creating change.

Are we involving our donors in movement-building opportunities beyond donating?

Research shows that Millennials are not necessarily interested in supporting specific organizations as much as advancing a specific cause. They also consider volunteering an important way to contribute to a cause. Are you providing meaningful non-monetary opportunities for people to participate in your organization’s work? Are those efforts clearly linked to advancing larger movements?

Are we digital?

Millennials are the first generation of digital natives. They’re accustomed to accessing information through their phones and other portable devices. Is your website mobile-friendly? Is it easy for first-time visitors to quickly determine your organization’s mission and program and why they’re compelling? Is it simple for someone to make a donation on a cell phone?

Are we encouraging planned gift?

The senior population will grow by 81 percent in the next 15 years. Now is the time to let donors know about the impact that planned gift can have on your organization. Donors of all generations can remember your organization in their estate plans. Planned gift are usually the biggest contributions individuals will make.

Moving Forward

For nonprofit fundraisers, the next two decades will involve building and deepening relationships with multiple generations, including younger and more racially diverse supporters. That work will be even more pressing for social justice fundraisers, since many of our organizations address issues of particular importance to the coming majority of people of color.

As people of color become more numerous, if not the majority, in increasing parts of the country, it is politically and financially vital that social justice organizations involve a diverse spectrum of supporters. Thoughtful planning today can ground your organization for success decades from now. Giving strategic thought now to how you can diversify your individual donor base can set up your organization to ride the swelling wave of diversity, rather than scrambling in its wake.

1 Frey, William H. Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographic Are Remaking America. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2015. 58-59.

2 Frey, 32

3 Frey, 25

4 Frey, 21

5 Frey, 241, based on U.S. Census Bureau Population Projections 6 Frey, 240

7 Frey, 34

8 Giving USA 2016: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2015 (2016). Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 73.

9 Frey, 50

10 Frey, 80

11 Frey, 99

12 Frey, 119

13 Frey, 122

14 Frey, 128

15 Frey, 142-43

16 Frey, 166

17 The Millennial Project’s findings are based on surveys and focus group interviews with more than 75,000 Millennials. The Project, however, does not include any racial/ethnic overlay. So it is unclear

if the Project’s sample is representative of this most racially diverse generation in American history,

18 Younger generations are almost always more liberal, so time will tell whether Millennials will maintain this liberal bent.

19 Millennials in Adulthood: Detached from Institutions. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, 2014. 22

20 Pew Center, 31-33

21 Pew Center, 9

22 2014 Millennial Impact Report. “Inspiring the Next Generation Workforce, 1

23 Pew Center, 9

24 Pew Center, 8

25 The Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, as cited in Giving USA 2016: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2015 (2016). Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 74.

26 The Ever Growing Gap: Without Change African American and Latino Families Won’t Match White Wealth for Centuries. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Policy Studies & CFED, 2016. 5.