Content warning: This podcast discusses sexual violence.

Amy Costello: In May, the US announced it would pull its troops out of Afghanistan. Around that time, Dorcas Erskine got in touch with our producer, Freddie Boswell. Erskine is an expert in gender-based violence and she’s been on our podcast before. She co-founded WeCie, an organization for women of color humanitarians. Its members work to address violence against women and girls in emergency settings across the globe.

Lately, she had been hearing from these women about conflicts across the globe—whether in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, or Burma (also known as Myanmar). Members of Erskine’s network were telling her that these conflicts were having direct impacts on women and girls. The violence and instability were also having direct impacts on these humanitarian professionals, and they told Erksine they felt alone.

Dorcas Erskine: There were three or four women in our networks who found themselves either having to run from the countries in question or feeling abandoned by the rest of the world to some essentially very horrific things that were happening. And these are all women who also, in their day job like me, work in the humanitarian sector. So, I guess we all have—not a naïveté, far from it, but a sense that there are processes and there is an international system that’s being set up to really respond to these kinds of atrocities, and no one was doing anything. There was almost a lethargic sense, or almost a shrug of, well, that’s just the way it is. And there’s a horror in that, I guess, for all humanitarians, but also for women living in these countries who essentially feel abandoned.

Costello: In Afghanistan, Zarqa Yaftali is director of the Women and Children Legal Research Foundation. She’s involved in the country’s peace process, and she told Freddie that when the US announced it would withdraw from her country, she felt abandoned, too.

Zarqa Yaftali: Unfortunately, when the US government announced their withdrawal from Afghanistan, the security threat against women became very high. In the last four months, we lost a large number of women who were civil society activists, women’s rights activists, and women from the media. And it is not finished. We are not living in a secure environment nowadays. It is not clear what will happen tomorrow, or what will happen next week, or what will happen next month in Afghanistan. So, I think, one of the causes that had a direct impact on the situation of women in Afghanistan was the withdrawal of the US government. And I am always emphasizing this: when the US troops came to Afghanistan 20 years ago, it was clear to all of us that they were going to leave Afghanistan one day. But unfortunately, they left Afghanistan without any strategic plan and program, so it has bad side effects on the situation of all people of Afghanistan, especially the women of Afghanistan.

Costello: As we hear directly from women in these countries, Erskine invites listeners in the West to keep one idea in mind. The idea she wants us to ponder is about an absence. A void. Invisibility. Erksine implores, “Think of all the women forgotten in the wars you started.”

Erskine: Yes, think of all the women you forgot in all the wars you started. And just think of what the world would be if they could live their full potential, if they could live lives that were meaningful and were uninterrupted by our mistakes. I mean, the tremendous loss of human potential that has gone on because of all the crises that we have, and then also our lack of commitment to address problems collectively as humanity, and our lack of commitment to keep the international promises and conventions we sign up to. When you sit down and you think of the tsunami of women’s lives that have been affected by our inaction or our careless action around the world, and our lack of responsibility in doing our bit to clean up our mess, it’s quite staggering.

Costello: So today, we want to highlight the struggles of those women in Afghanistan, in Ethiopia, and in Myanmar. But we also want to focus on their strengths. Because the international community might seem to ignore or forget what these women and girls are enduring every day and every night, but often it’s women locally who step in to provide support and even bring about change in their own ways. But Erskine says this significant work that local women provide every day just isn’t taken seriously by the humanitarian hierarchy in the West.

Erskine: One of the biggest gaps we have in our international system that we pay lip service to is that we must involve local people. We must involve women in terms of leadership, in terms of the peace process. But we, in practice, barely do that. And speaking to all of these women, you realize they do show up, they know what they’re doing. They have particular tools around peacebuilding. They have particular things to offer as people living in their countries. I mean, one of the saddest pictures around some of the peace processes around Afghanistan, again, was to see how few women were involved in that process and how their numbers, as the process went on, began to dwindle. No one is actually, really, meaningfully involving the other half of humanity—women—in these discussions. There’s a paralysis around it, almost a depressing silence, almost an eyeroll that these are things we must take care of, but they are “lesser than”—you know, women’s rights are lesser than consideration. Women’s rights activists are a lesser-than consideration than this wider idea in people’s minds, in some people’s minds internationally, who lead these kinds of conversations around what security really means. So women’s security, which is all our security, is sacrificed on the basis of really a masculine idea of security that doesn’t include them in its conception of what real security is for the world or how to bring about a greater peace. And we’re in 2021 and we’re still having that discussion, and that’s pretty, pretty depressing.

Costello: In Afghanistan, Zarqa Yaftali points out that there are only four women on the negotiation team involved in the peace process in Afghanistan. And as a woman involved in peacebuilding herself, she admits that every day she faces threats to her life. She has to be careful planning her route every time she leaves her house. And she stays with this work anyway, because there is nothing else she can imagine doing, and she’s known that since she was a child.

Yaftali: When I was a child, I had a dream that I would work for the women and children of my country, because I was born in conflict, in a country where there is conflict, so violation and violence against women and children is a common issue. And because of this, I decided I will work for the women and children of my country. And when I graduated from the faculty of Law and Political Science of Kabul University, then I started my work for the women and children of my country, and I can raise their voice. I can advocate and lobby for their rights in my country. Also, I got to be part of the decision-making and also a part of the law-drafting committees in Afghanistan.

Costello: That calling to make life better for your fellow women and children is echoed in many women across the globe. Fanaye Solomon is a social worker and women’s rights advocate for women in Tigray, Ethiopia. She’s an Ethiopian herself, living in exile in Australia, and she’s driven by the same impulse that fuels the work of Zarqa Yaftali in Afghanistan. It’s this quiet but persistent call she’s heard most of her life—to go back to Ethiopia one day and do something to make life better there for future generations. But during a visit to Ethiopia, Solomon saw a scene unfolding before her, and it crystalized everything for her.

Fanaye Solomon: The moment the evidence shifted for me was, I saw a mother carrying this heavy, heavy wood on her back and walking, and I’m sure she would be walking for hours before she gets home. And then next to her, her daughter, who was probably maybe six, seven years old, also carrying the wood on her back that she could carry. That’s when I opened my eyes and I said: OK, the mother is carrying wood. The problem for me was her daughter is doing the same thing. We are raising the next generation to have the same struggle. And for me, I would have probably felt a lot better if I saw her walking next to her carrying her books, because she had just picked her up from school. And that’s when I said, we have to do something. We have to do something. The next generation has to be better than the previous one. So, I kind of took it as my responsibility to get involved and to make sure that the next generation coming would have a better life than those before them.

Costello: Solomon decided to help by setting up a one-stop-service center—essentially a safehouse in Tigray where survivors can report and be treated for sexual violence. And things for women and girls have gotten worse since November 2020 when a war erupted in Ethiopia having to do with Tigray’s autonomy. Reports say that at least 10,000 people have died and 230 massacres have been committed. Women have been brutally targeted. Solomon is seeing the results among the women who are walking into the service center she founded.

Solomon: Sexual violence is being used as a weapon in the war in Tigray today. So, the one-stop-service center today serves, maximum, 11 women a day, who would come in there and report sexual violence committed by these soldiers, and if it’s on a good day, and it’s not really a lot of people, it will be six to seven women that will come in and report, and that’s on a daily basis.

Costello: In fact, the UN kind of conservatively estimates that 22,000 survivors of rape in Tigray will need support.

Solomon: There is no safe place for women in Tigray. They are being raped in their own home, on their way to the shop, at the workplace. I mean, your home is meant to be your safe place, but they’re not even safe there. They get abducted from their own home. Things are looking really, really bad. Women are raped and horrific harms are inflicted upon them; the type of harm is unimaginable. When you hear them, when you get the reports, it’s hard to believe that’s actually happening, and people can actually do that. But they’re not only being raped. They are being humiliated, traumatized, but they are also losing their lives, their legs, trying to protect themselves from being raped by these soldiers. They have seen their sons, their husbands, their brothers being killed in front of them, trying to protect them, and therefore, after they’re raped right next to the bodies of their dead husbands and sons and brothers. This is exactly what’s happening in Tigray. And we haven’t even heard most of it. Those that are reporting are those that have the courage to actually come forward, or those that have had severe injuries and need immediate medical support, or fear pregnancy. But then there are also many women that do not have the access, that are scared to report because of the stigma and threat from the soldiers, and actually do not trust that they will be able to get the support, and instead could be killed, or raped again.

Costello: Wow. That’s a lot to take in, isn’t it?

Solomon: It is a lot, but…it is, yeah. It’s hard. It’s hard to believe. It’s heartbreaking. And the fact that, you know, the world is watching and being concerned, but unfortunately, being concerned is not enough and it can’t save or protect these women.

Costello: I want to talk to you for a moment about the strength and power of women in Tigray. Before this war came, talk to me about what you recall about their strength, about their power.

Solomon: The women in Tigray, they are my inspiration. They are the most strong and internally powerful women that I have ever met. You know, they might be disadvantaged in so many ways within our society, but they never lacked the power to stand side-by-side with the men in our society in rebuilding our country, in holding down everything that they need to hold on to be able to rebuild our country. The hard work and the commitment they put in to create a better country for the next generation. And still today, despite all the pain and all the suffering that they are going through in this war…you know, you call home and talk to the aunties and families, and I also talk to other women that are not related to me, but they are facing other issues. Still, you can see that determination, that strength that’s within them. And they will be there, and trying to comfort us that are here about what they are facing there. They always feel like someone else is worse off. Another woman would come and report, and the other one would say, she’s worse off. One woman said, you know, at least they wore a condom when they raped me, so I’m better than the other ones, so please, can you help these other women before me? These are the women in Tigray. And that strength and determination and commitment to their families, to their country and everything, taking responsibility—not only for their husbands and their families, but taking responsibility, and giving and sacrificing their life, even for their country. This is how I would describe the woman in Tigray. And they’re very humble. Very humble.

Costello: Was there a particular moment you remember when you would visit home that kind of exemplifies what you’re talking about? Did you ever kind of gather with a group of women, for instance, or meet a certain woman who you kind of think exemplifies the spirit that you’re talking about?

Solomon: One woman that inspired me so much was a woman who got married when she was 12 years old, and as a result of early pregnancy, she was a victim of fistula. She was unwell for a long, long time, and suffered and had struggled for many years, and throughout her recovery and her journey faced all kinds of challenges a woman could ever face. I met her, and she lives in a village. She doesn’t have much; she has very, very little. But that woman walked for hours to different areas and villages, speaking to young women about early pregnancy and how damaging it can be. But also going from one place to another voluntarily, making sure that if there are young pregnant women, they get the medical treatment to have a healthy pregnancy. And I said to her: why are you doing that? This is voluntary, and you’re walking for days? And she said, “I don’t want any other woman, no other woman in Tigray, to go through what I went through. I don’t want our children, the next generation, to live the life that I lived.” She was taking responsibility and making sure to prevent what happened to her as a child. And there are many women like that in Tigray.

Costello: It’s interesting; when I hear you tell the story of that woman, I hear echoes of you, in Australia, far from your home, kind of shouting from the rooftops—whether it’s on Twitter, whether it’s in media interviews, whether it’s in speaking to me. I see you in a way, walking village to village, telling anybody who will listen about what’s going on in your home. Do you see yourself that way?

Solomon: I never really reflected and looked at it the way you just said it. For me, I think, just like that woman that inspired me, I’m just doing what I feel is my responsibility. And it is making sure that the voice of the women in Tigray is heard, because they don’t have a voice at the moment. It’s my duty. And unlike those women in Tigray, I have the privilege to have a voice and to speak up, even to be heard. So, I wouldn’t compare myself to the woman that I talked to you about, because she does all that despite all the struggles that she’s facing and that she’s going through. But for me, no matter how much pain I’m in because of what’s happening in Tigray, I’m still here, in my comfort zone, and I have the opportunity and the right to actually go to different platforms and speak about what’s happening in Tigray.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Costello: On the other side of the world, women have also been trying to draw attention to the situation in Burma, or Myanmar. In April 2021, the military seized control from Nobel Peace Prize-winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s ruling party and declared a yearlong state of emergency. The country has seen some of its largest protests in response. Twenty-nine-year-old Thinzar Shunlei Yi is a youth advocate and activist. And despite the personal risks she faces, she is completely determined to take to the streets, continuing to demand change. She knows Myanmar has seen violence before. This is not the first time.

Thinzar Shunlei Yi: This is not the first time, but this should be the last time. And that’s why we are so determined to invest everything we have, even our own lives. For myself personally, the driving force to keep going forward is the principle and the values I believe in. I’m standing on firm ground that is not shakable and not stoppable. That’s how I think I keep on going. And there’s no other option but just to keep moving forward. Obviously, the work I’m doing is so painful and so mentally draining every day by just monitoring what’s happening. But I think our generations have to be strong and resilient in that matter because we don’t want to pass these experiences to our younger generations, to our daughters, nieces, brothers, and sisters. Being born in Myanmar, we have no option.

Costello: Well, I guess your option could be to stay quiet and stay home. I mean, I’m sure there are many, many women who do stay home, who stay quiet, who don’t want to draw attention to themselves. I mean, in some ways, you are making a choice.

Shunlei Yi: Yes, that’s true, that’s true. I think other women might have a choice, but for myself? Personally, I was born as a Burmese Buddhist, in the majority, with all its privileges. And also, I was born in a military unit. So, all my life, until I was 16 or 17 years old, I was in a military unit, and I didn’t know anything that was happening on the ground to the ethnic minorities. So when I learned about the atrocities committed by people of my own background, that shocked me. And since that time, I have devoted and committed myself to work harder than others, risking my life, picking unpopular topics to shake the ground, to challenge the status quo so that we have a better future. And I think I’m doing that as a full purpose of my life, and that’s meaningful to me.

Costello: So, you were born into the ethnic majority Burmese population and in a military family, and now you’re advocating for the rights of everyone in your country, including the ethnic minorities. How has your family responded to that?

Shunlei Yi: My family did not support me in the first place because they knew it could be risky, not just to me, but also to them as well. And in this situation, they can get arrested at any time, just because of my activism, and they could be kicked out of the house that we live in, for example. But I believe I was raised to be independent and to find the true meaning of life.

Costello: As Thinzar Shunlei Yi lives out that true meaning, over 50 women have been killed in protests in Myanmar so far, and around 1,000 women have been arrested. The Burmese military is known to be brutal, patriarchal, and misogynistic, and women continue to face sexual violence, harassment, abuse, and threats from the junta, who have not appointed any women leaders. But Thinzar Shunlei Yi recognizes that women—and especially young women—are leading what she now calls a revolution.

Shunlei Yi: As we look forward to forming a new, federal democratic nation in our future, we are also looking at a new society to step in. And that’s how we, the young, and young feminists, step in to change the narrative, because feminism is also growing. It’s changing every year from a different perspective. It’s trying to be more equal and respects all different sorts of gender or sexual orientations. And so I believe the role of the younger feminists, the younger women in Myanmar, also plays a huge role. So when we talk about women, we all have to look at the important role and challenges that younger women are facing in society.

Costello: I’ve been reading about the way that women are using traditional clothing and sometimes feminine hygiene products to protest on the streets. Can you talk to me a little bit, describe how women are using their own clothing to kind of hang over the streets as a form of protest?

Shunlei Yi: Women’s clothes and sarongs, for example, and menstrual hygiene products, in this misogynist society, are seen as a threat to their superpowers. It’s a sort of a power that they believe in based on traditional religious norms. So, when the women hang their sarongs on the streets, soldiers and policemen who believe they have bigger power, or supremist power, do not feel they can cross them. Women and women’s groups are using our products as a way to defend ourselves, because these military, evil people, terrorists, are afraid to touch these women’s things. And since that time, we are seeing a rise in the movement of young progressive men who don’t have those kinds of beliefs, and they easily wrap the women’s sarongs on their heads, so that also shows us that our younger generations have progressive thoughts on the women’s products. So we see this revolution, what’s happening in Myanmar, is not just a political revolution. It’s more than that. It’s a cultural, ideological revolution that includes smashing the patriarchy in society. And that’s how I feel change is inevitable in the revolution, and that’s how we see our future as feminists.

Costello: Under Taliban rule, Afghan women faced harsh, sometimes public punishment for living their lives independently. Twenty years since the war with the US, Zarqa Yaftali has seen a change and confidence in the women she works with to live more freely, but she’s aware that those early days of spreading freedom and feminism, well, have largely been forgotten by the American public.

Yaftali: They don’t have the attention that they had 20 years ago for the people of Afghanistan and the women of Afghanistan. But for us, this time is very important. We want solidarity, and also the support from the international community for the people of Afghanistan, and especially the women of Afghanistan. Because 20 years ago, when they came to Afghanistan, at that time, there wasn’t any need for them to come, but now there is lots of need for them.

Costello: That’s because, Yaftali says, 20 years ago in Afghanistan, there weren’t that many people familiar with issues like women’s rights, democracy, and freedom of speech.

Yaftali: But now, these issues hold important value for us, so it is important that we have their support and solidarity at this critical time. But unfortunately, nowadays, as we are seeing, they take the position of silence. They should support the women of Afghanistan in this critical time to protect our achievement, to develop and design a brighter future for our children. Because nowadays, there’s a lot of concern that Afghanistan will go back to the years of 1996 and 2001. At that time, there wasn’t any chance and any opportunity for women to work, to continue their education, and also to be part of society. We had very bad experiences at that time. And now we’re concerned that those days will come again to Afghanistan, and history will repeat itself. Because of this, I am calling on the international community to please abandon your silence and stand in support of the achievements that we have made in the past two decades.

Costello: Fanaye Solomon also feels silence from the international community over what is happening in Tigray. She fears it’s like the Rwandan genocide, and how that was made possible because of international inaction.

Solomon: I don’t feel like the world is watching. I don’t think the world really understands how severe and to what extent things are actually happening in Tigray. I think they’re looking at it like, there’s a conflict, which is the usual thing, the common thing in Africa. There are conflicts and people die. I mean, they’re hearing our screams, but I don’t think they are listening. I don’t think they really understand what’s happening there. And I guess like everywhere else, in Rwanda and everywhere else in the world, probably, when so much damage has been done, so many people have died, and then they realize that it was a little bit too late for them to do anything and that they wish that they had acted sooner. So, this is pretty much what I’m expecting from them, because, what is happening in Tigray, I believe they will eventually have to come forward and apologize to us and to the world that they didn’t actually take action in time.

Costello: So, Dorcas Erskine wants people to really tune in to what is happening. Hear that energy and bravery in Thinzar Shunlei Yi’s voice when she talks about why she confronts the military on the streets of Myanmar. Erskine wants us to recall the pride Fanaye Solomon has for her fellow Ethiopian women. She challenges us to be moved by the dedication Zarqa Yaftali demonstrates to peace every day in Afghanistan. Each woman represents a bright spot for us to focus on, to get behind. Yes, Dorcas Erskine wants us to “think of all the women forgotten in the wars we started,” and she also wants us to remember their power and their potential.

Erskine: I don’t want to end on a note of depression. I think this podcast will make for some hard listening, and often when you hear things that are hard and difficult, you do get a sense of fatigue and weariness. And I just don’t think that’s what these women embody for me. And I hope that people listening hear the energy of these women, their dedication, and their passion. And if they could imagine a world in which this wasn’t their lives, what kind of lives these amazing women would have. If their life’s work wasn’t basically “don’t kill us, don’t hurt us, don’t rape us,” what could they do? I think the potential of what people could do would be staggering. And that excites me, and I hope it excites people who are listening to your podcast and moves them to ask their governments to do better. And, if there are any politicians listening, to make them pause and feel they can do something, their options aren’t limited. They should be brave, and we would support them in that.

Costello: And Zarqa Yaftali says, for her three kids, she wants them to grow up with the same opportunities as kids anywhere else in the world.

Yaftali: I love that they are growing up in Afghanistan, and I hope that the security situation becomes stable and becomes good, and we find the opportunity to live in our country without any concerns or difficulties. So, I really love that my children grow up here in Afghanistan, and hope that one day they’ll do lots of things for their country and for their people.

This web version of the broadcast has been lightly edited for clarity.

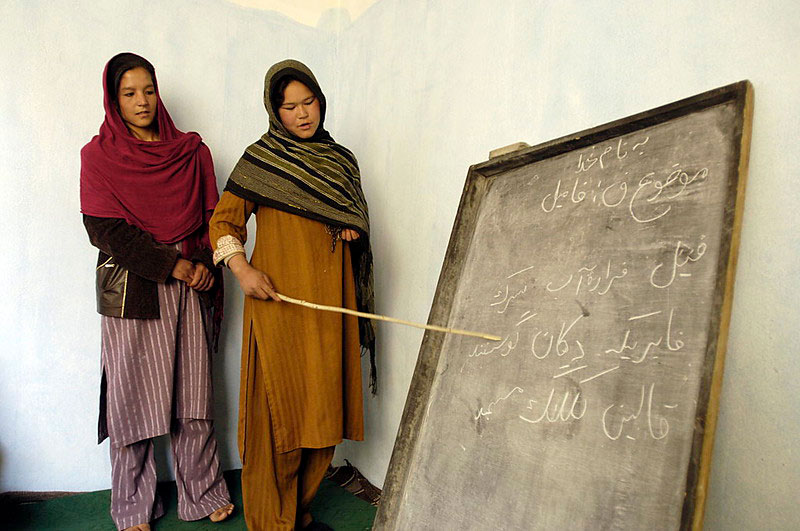

Cover Photo: “Afghan Women in Literacy Class,” United Nations Photo

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Emma Graham-Harrison, Akhtar Mohammad Makoii, “After the retreat: what now for Afghanistan?” The Observer, July 4, 2021.

Lynsey Addario, Rachel Hartigan, “A grave humanitarian crisis is unfolding in Ethiopia. ‘I never saw hell before, but now I have,’” National Geographic, May 28, 2021.

Michelle Onello, Akila Radhakrishnan, “Myanmar’s Coup Is Devastating for Women,” Foreign Policy, March 23, 2021.

Ei Hlaing, “Myanmar’s anti-coup protesters defy rigid gender roles—and subvert stereotypes about women to their advantage,” The Conversation, May 12, 2021.

On Twitter: Thinzar Shunlei Yi, Fanaye Solomon, and Zarqa Yaftali