This article comes from the spring 2019 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

From the outside, it can look like the nonprofit sector, because it is tax exempt, does not contribute to government tax bases at all. That one-sided view wildly misses how this part of the economy works even at the most basic level.

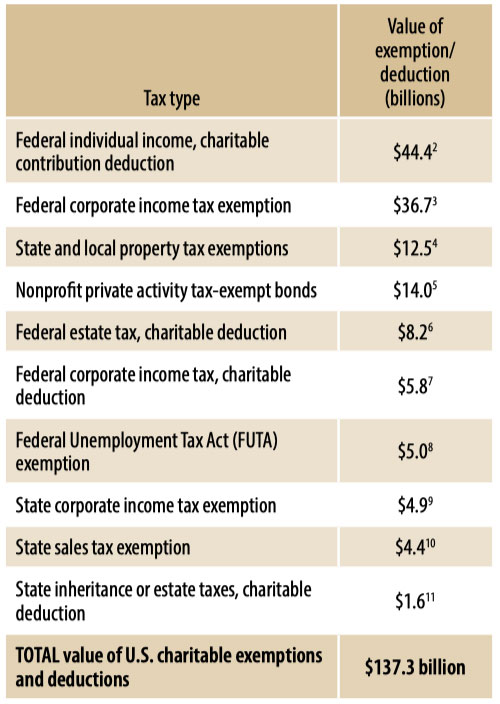

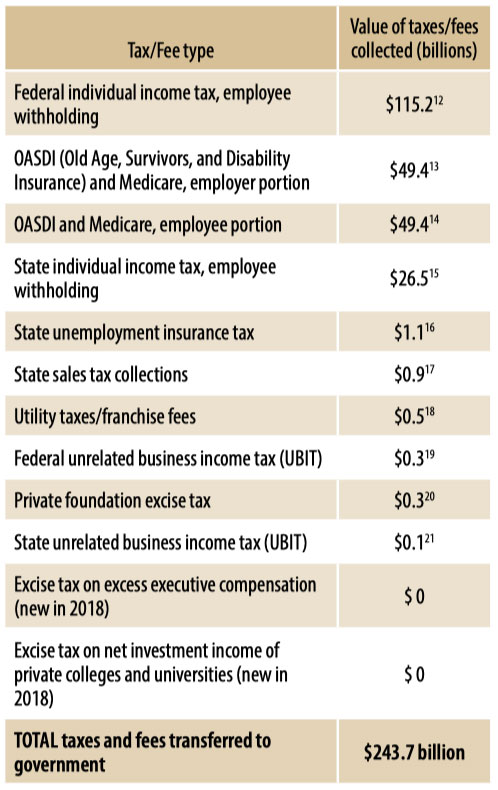

It is true that in 2015, U.S. nonprofit organizations benefited from somewhere in the neighborhood of $137 billion in tax preferences from exemptions and deductions—but at the same time, they sent approximately $243 billion to various government entities in the form of taxes, tax withholding for others, and fees.

In other words, even though they are sometimes considered to be an essentially “tax-free” sector of the economy, nonprofits clearly have deep involvement on both sides of the ledger: as a tax expenditure, in the sense of forgone revenue, and as taxpayers and tax collectors, making substantial contributions to government revenues through tax collection from nonprofit employees and activities. This side of the ledger is not often examined, so this rough estimate is offered as a clarification that nonprofits are by no means tax negative (or even tax neutral).

The two charts below capture nonprofit tax activity in 2015 across a vast array of U.S. jurisdictions—federal, state, and local—in a variety of tax transactions. The IRS reported that charities held over $3.8 trillion in assets and received $2.9 trillion in revenue during that tax year.1 These projections are my initial effort to quantify (in a necessarily gross estimate) the national value of charitable nonprofit benefits and obligations across the various taxing systems.

Charitable organizations’ exemption from federal and state corporate income taxes has been the most visible charitable tax benefit, but the actual value of the corporate income tax exemption is probably less than imagined due to the lower net margins of income over expenses among nonprofits. The projected benefit of this part of the exemption will shrink further, to $20 billion in 2018—with the marginal federal corporate income tax rate reduced by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, from 35 percent to 21 percent.

The economic activity generated by nonprofit organizations results in substantial collections and transfers of taxes and generation of fees. The vast majority of total federal revenues is collected through the individual income tax (49 percent in FY 2019) and Social Security and Medicare taxes (36 percent), compared to the 7 percent share coming from corporation income taxes. At the same time, nonprofit employees tend to receive only ordinarily taxed income as compensation, while for-profit employees may have access to equity participation, capital gains treatment, and other individual income tax preferences, lowering their effective rates.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Nonprofits are actively engaged in collection and transfer of taxes from their employees, an obligation with penalties of fines or imprisonment for failure to pay (including for board members!), and are required to pay a variety of taxes and fees to the federal, state, and local governments that are not subject to exemptions—adding up to $280 billion in 2015:

Further Thoughts on the Nonprofit Place in the Tax World

Nonprofits benefit financially from these tax preferences, so by extension they, as organizations, benefit from the public’s expectation that they must truly benefit the public if they are accorded their special status. This can also translate into preferences for government to contract with nonprofits in certain subject areas, such as human services and child protection. Some of the most interesting qualitative and tax comparisons come from activity areas where nonprofits and for-profits compete for the same customers—hospitals, higher education, child care, nursing homes, home healthcare, student loans, low income housing, and so on.

Tax preferences can have a push and pull effect, encouraging particular types of activities. Nonprofits in English-speaking countries have the greatest tax preferences and also have the largest nonprofit sectors. In these countries, the signaling that these organizations are in large part not taxed can encourage charitable contributions and volunteering.

Like other parts of the economy, nonprofits jealously seek to guard their tax preferences (and who can blame them?), and often find themselves in a tug-of-war with different parts of state and local government that also are seeking revenues, as noted by Tim Delaney in “Nonprofit Tax Policy: A Game of Three-Dimensional Chess” (in this section of the magazine). Each side seeks to make its strongest arguments for its role as essential service in a battle of competing goods when it comes to sales and property tax exemptions. It’s worth noting that units of government don’t pay sales or property taxes either, and no one suggests taxing the police department to pay for the fire department (and no one has been able to make federal buildings pay local property taxes).

Another stress point can be found between for-profit businesses and nonprofits, both over UBIT and over property tax exemptions. Claims of unfair competition have been raised historically by the National Federation of Independent Business, resulting in a few line-drawing changes in UBIT applicability. Nonetheless, concerns over the substantial growth in the economic activity of nonprofits—some of it seen as essentially commercial—have not risen as high on the business lobby agenda as they did in the late 1980s.

A simmering issue underneath the various tax conflicts is the sheer growth of the medical and higher education sectors. For much of the general public, these prosperous institutions do not look like charity cases marked by modest salaries, nondescript buildings, and substantial grassroots fundraising. As the medical field consumes a growing portion of the gross domestic product—and so long as nonprofit hospitals are 99 percent fee driven—other taxpayers could well wonder how that industry rates its special preference. When the property tax exemptions were written into most state constitutions (in the 1800s), the colleges and hospitals were just getting started—usually with religious roots, certainly of modest size. Those contentious funding mechanisms PILOTs (payments in lieu of taxes) may well gather support as a timely and sensible compromise for these large institutions.

Notes

- “Charities and Other Tax-Exempt Organizations, Tax Year 2015,” Internal Revenue Service publication 5331 (Rev. 12-2018), Catalog No. 72046Q. (Comprehensive IRS data on nonprofits after 2015 aren’t available.)

- Projected forgone tax revenue from donors’ tax obligations from 2015 individual income tax charitable contribution deductions. Total charitable deductions of $221.8 billion (IRS SOI [Statistics of Income] Individual Income Tax Returns, Line Item Estimates 2015), with an average effective individual tax rate for itemizing taxpayers of 20 percent. For itemizers, generally the higher the individual’s income, the greater the share of his or her deductions made up of charitable contributions—so the actual average tax rate avoided for charitable contributions may be higher.

- Projected forgone tax revenue from 2015 corporate income tax based on 501(c)(3) net income of $104.9 billion and 35 percent corporate tax rate (IRS SOI Nonprofit Charitable Organization and Domestic Private Foundation Information Returns, and Exempt Organization Business Income Tax Returns: Selected Financial Data, 1985–2015).

- Projected forgone property tax revenue from 2015 state charitable property tax exemptions, extrapolated from total reported charitable property of $1.045 trillion in land, buildings, and equipment (IRS SOI, Table 3, Form 990 Returns of 501(c)(3)-(9) Organizations: Balance Sheet and Income Statement Items, by Code Section, Tax Year 2015). If 80 percent of this $1.045 trillion value is subject to the property tax, and the average commercial property tax rate is 1.5 percent, the forgone property tax would be $12.5 billion.

- Projected forgone income tax revenue in 2015 from holders of $102.4 billion in private activity tax-exempt bonds issued in 2015 by state and local governments for debt financing public benefit private projects, such as private universities, hospitals, affordable rental housing, funding and refinancing student loans, etc., on a tax-exempt basis under federal income tax laws (IRS SOI Tax-Exempt Private-Activity Bonds, Form 8038). (Author’s estimate.)

- Projected forgone tax revenue from donors’ charitable deductions from 2015 federal estate tax, $20.4 billion in charitable bequests made from estates exceeding the 2015 $5,430,000 estate taxable threshold, 40 percent tax rate (IRS SOI, Estate Tax Returns Filed in 2015, Gross Charitable Bequests).

- Projected value of federal corporate income tax, charitable deduction, based on $16.7 billion in charitable contributions, 35 percent tax rate (IRS SOI, 2013 Corporation Source Book of Statistics of Income).

- Projected value of exempted 2015 federal unemployment tax payments (FUTA rate of .06 applies to first $7,000 of an employee’s payroll; 12 billion nonprofit employees) due to nonprofit FUTA exemption.

- Forty-two states and many localities impose a tax on the net percent income of corporations, which may be a single rate or progressive within brackets. Projection applies an average 6 percent state corporate tax rate on net income across all charitable organizations to 501(c)(3) net income of $104.9 billion.

- Forty-five states collect sales taxes on purchases within their state, and local taxes are collected in thirty-eight states, ranging from 4 to 10 percent, with an average combined tax rate of 8 percent (Jared Walczak and Scott Drenkard, “State and Local Sales Tax Rates 2018,” Fiscal Fact No. 572 [Washington, DC: Tax Foundation, February 2018]). Charitable organizations can apply for an exemption from paying the sales tax in most states, but the process and eligibility vary greatly, and are rarely coexistent with 501(c)(3) status. (Author’s estimate, based on reported 990 functional expenses typically subject to sales tax, including portions of meeting expenses, office expenses, and other expenses [IRS SOI Form 990 Returns of 501(c)(3)-(9) Organizations: Total Functional Expenses, by Code Section, Tax Year 2015].)

- Fifteen states and the District of Columbia had estate taxes in 2015, with tax rates ranging from 9.5 percent (Tennessee) to 20 percent (Washington State) at the top end, with most at 16 percent. Projected $1.6 billion forgone tax revenue from estates’ charitable deductions from 2015 state estate taxes, based on $9.9 billion in charitable bequests reported for these sixteen jurisdictions (IRS SOI, Estate Tax Returns Filed in 2015, Gross Charitable Bequests, by State of Residence).

- Projected federal individual income tax employee withholdings for national nonprofit payroll of $661.8 billion (IRS SOI, Salaries and Wages, Compensation of Officers and Other Persons, Table 3, Form 990 Returns of 501(c)(3)-(9) Organizations: Balance Sheet and Income Statement Items, by Code Section, Tax Year 2015); average federal tax withholding in nonprofit compensation ranges of 17.4 percent. (Author’s estimate, based on IRS recommended withholding tables.)

- OASDI and Medicare—employer portion based on payroll of $661.8 billion. Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) requires that employers make contributions to Social Security and Medicare out of every paycheck. The Social Security tax rate for employers in 2015 was 6.2 percent on income up to $118,500 and the Medicare tax rate of 1.45 percent of all income levels. An estimated 3 percent of payroll was for individuals who exceeded the $118,500 maximum taxable earnings. (Author’s estimate.)

- OASDI and Medicare—employee portion is equal to employer portion (6.2 percent on income up to $118,500 plus the Medicare tax rate of 1.45 percent of all income levels).

- Forty-three states have individual income taxes, thirty-three with graduated tax rates; projected total state income tax withholding is based on 4 percent of national nonprofit payroll of $661.8 billion. (Author’s estimate.)

- Nonprofit organizations have the option of becoming direct reimbursers to pay unemployment claims, opting out of paying into state unemployment systems (under IRC §3303(e)), an option taken by most large nonprofit employers. This amount reflects the number of nonprofit employers remaining in state UC systems. (You can find more on this at chooseust.org.)

- When charitable organizations sell tangible goods or services that are subject to sales tax in their state, they are required to collect the tax and forward it to the state in the same way as businesses, unless the item is subject to an exemption. The list of items subject to sales tax varies widely by state, as do the lists of organizations or activities that qualify for charitable exemption. For example, almost every state has exempted Girl Scout cookies from sales tax, while many states allow fundraising events with time limits (such as limited to 30 days or less) to be free from collecting sales taxes.

- A variety of federal, state, and local communications, utility, franchise and access taxes, and fees and charges can be applied to telephone, Internet service, and electrical and gas services, with no provisions for charitable exemptions. (Author’s estimate is based on reported Form 990 functional expenses, including portions of information technology, office, and other expenses—IRS SOI Form 990 Returns of 501(c)(3)-(9) Organizations: Total Functional Expenses, by Code Section, Tax Year 2015.)

- The 2015 unrelated business income tax (UBIT) payments by 501(c)(3) organizations were extrapolated by the author projecting 4 percent growth from 2013 tax payments (IRS Statistics on Income, Unrelated Business Taxable Income [Less Deficit], Unrelated Business Taxable Income, and Total Tax, by Type of Tax-Exempt Organization, Tax Year 2013).

- IRS SOI, Excise Taxes for Year 2015 Reported by Charities, Private Foundations, and Split-Interest Trusts on Form 4720.

- Most states impose a tax on nonprofits’ unrelated business income, reflecting the state’s corporate tax rate, but they can differ in how they apply it and what is covered. Projection applies an average of 6 percent state corporate tax rate on net unrelated business taxable income of $1.9 billion (IRS SOI, Nonprofit Charitable Organization and Domestic Private Foundation Information Returns, and Exempt Organization Business Income Tax Returns: Selected Financial Data, 1985–2015).