May 22, 2017; Post Independent (Glenwood Springs, CO)

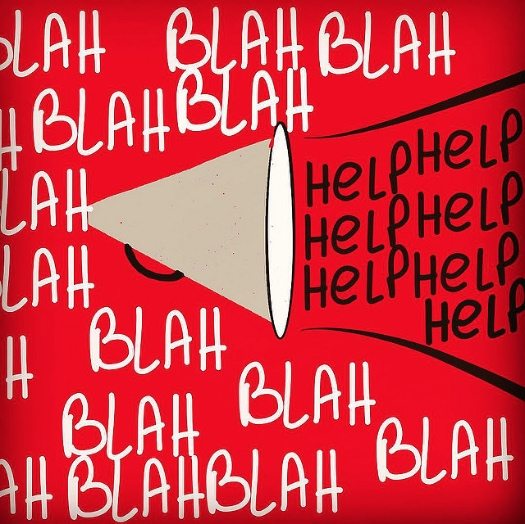

The Glenwood Springs Center for the Arts is broke, and its staff and some of its board members have been trying for years to get someone to pay attention, even long enough to contract for an audit. This is one of those art centers that depend in part on a deal with the city for sustainability. In fact, Christina Brusig, its executive director, was paid by the city. But it also has its own board and financial accounts, and therein lies a problem, because evidently no one has wanted to take responsibility for investigating the multiple complaints made about the financial management of the center or the executive director, who was seen by some as being responsible for its problems over a period of three years.

Now, Glenwood Springs police are involved in an investigation that was finally sparked mere days after Brusig resigned in early April. The city’s funding for the center has been cut, and amid a forensic audit, and the question of closing the center down forever came up.

The Post Independent found that the city was tipped off about the situation repeatedly, starting in 2015, and some of the tips about Brusig came from board members. In one case, when board members asked for an audit, the city simply emailed the request to Brusig herself with a note explaining that the city did not have any administrative capacity to intervene.

Fast-forward a couple of years’ worth of missed paychecks, overdrawn accounts, and money raised for one purpose perhaps being used for another, during which time the board couldn’t see a way to do something. The bookkeeper resigned around September 2015, writing in her resignation to the board,

During my ten years working as bookkeeper for the Center for the Arts, I have never seen the Center for the Arts in such poor financial shape…When I have tried to address these concerns with Christina, she has told me not to worry. But I do worry. And it’s been keeping me up at night for quite some time. I simply cannot afford to continue to have this level of stress in my life.

Still nothing.

A former ballet instructor at the art center, Dana Peterson, sent two emails to the city’s human resources director reiterating the same concerns in 2015. Peterson told the Post Independent on Monday that she also had tried to tip off the city’s human resources department twice in 2015 and was turned away.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Then, on April 5th, Brusig resigned. (Brusig since has said her leaving was by mutual agreement with the board and that she had been working too many hours with inadequate support.) The next day, the board sent this note to City Manager Debra Figueroa: “Thanks for meeting with us today. It really has been a rough day; particularly regarding staff upset about the disruption to their lives and their checks bouncing. One employee was upset as her rent was due today, and I didn’t really know what to tell her. You’d better believe I’m hearing about it!”

The city agreed to pay a $20,000 advance to get staff paid.

On April 10, McRaith wrote to Figueroa that she was “very disturbed” by what they had learned about the art center’s bookkeeping issues. McRaith said staff had shared suspicious stories “that involve reputable bookkeepers who (stopped) working at the center because they were nervous about what was happening, disappearances, and replaced hard drives on the financial computer.”

Stacey Barnum, the art center board’s treasurer, emailed Figueroa on the same day with a list of recently discovered issues. She reported finding accounts that didn’t show the history of money that they should have, possibly other art center accounts at a different bank, overdrawn accounts, multiple accounts for Summer of Music, an account that had been closed by the bank after too many days of insufficient funds, money that wasn’t there for Dancers Dancing costumes even though parents had been billed for the costumes and costumes that had never been ordered.

Art center staff had also told Barnum “that some information presented at various board meetings concerning grants that had been awarded to the art center, employment of a part time grant writer, and the purchase of a $10,000 grant software program were most likely false,” Barnum wrote. “Many teachers have had their paychecks bounce this week and historically we are discovering that payroll has been spotty,” she wrote. “Some teacher’s checks have bounced more than once.”

Meanwhile, Brusig’s final paycheck included more than 200 hours of vacation time. Apparently, she did not take any vacation from 2015 to 2017—which, by the way, is a red flag for potential financial problems.

As the police investigation started, the two board members who originally sent the city their list of concerns forwarded it to the city again with a note suggesting that the whole meltdown could have been prevented had they just taken their warnings seriously. The city’s April 28th press release, which announced the funding cut to the art center, “continued to emphasize that it has no supervisory responsibility over the art center and its director.”

The city attorney has called the oversight situation at the arts center “awkward” and an arrangement that probably needs to be looked at. That is, if the center survives.—Ruth McCambridge