August 2, 2018; Crux

Xavier University of Louisiana and its Institute for Black Catholic Studies (IBCS) announced a new initiative to unite groups working on the promotion of Black canonization causes. (This is not the first time NPQ has shone a light on “The Lessons of Black Catholics for Modern Civil Rights.”)

The groups are presently gathering scholarly research necessary to elevate the following five candidates from the 18th through 20th centuries to sainthood: Venerable Pierre Toussaint, Venerable Henriette Delille S.S.F., Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, O.S.P., Father Augustus Tolton, and Julia Greeley. Auxiliary Bishop Joseph Perry of Chicago is spearheading the project. Other stories of potential saints will be added in the future, as new causes open.

The Catholic Church has canonized many African saints, but, among US Catholics, there are no Black saints. Canonization is the act by which the Church declares that a deceased person is a saint. Over time, rules were developed in ever-greater complexity to manage this process. It can take decades, or even centuries, and involves four official stages. These stages are Servant of God; Venerable; Blessed (the Congregation for the Causes of Saints investigates a miracle attributed to the candidate); and finally, Sainthood, when at least one more miracle is observed and investigated. The Holy See then makes the decision. Advocacy for Toussaint began in the 1970s.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Xavier University of Louisiana is the only historically Black and Catholic university, established 1925 by Saint Katharine Drexel and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. Xavier’s IBCS, founded in 1980, offers training for Catholic ministry. IBCS will construct a special center in which will be exhibited scholarly works about the lives of the Blacks in the US whose sainthood causes are open.

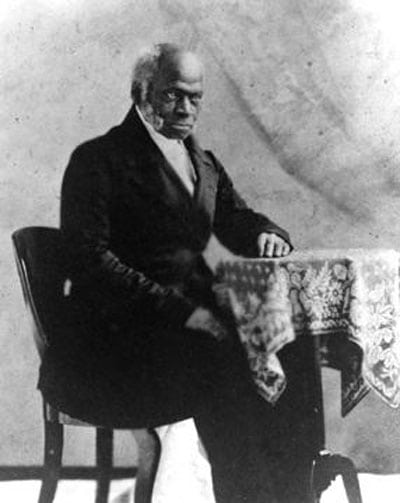

- Venerable Pierre Toussaint (1766–1853), a former slave in what is now Haiti, was brought to New York City and became a wealthy hairdresser. He purchased his freedom with the earnings from his trade. He was known for offering financial aid to those in need, as well as caring for the sick and orphans. He opened up the first Catholic orphanage in the city, which became the first school for black children in the country. Toussaint stayed in New York City during a cholera epidemic to care for those who were afflicted, eventually establishing what came to be known as Catholic Charities.

- Venerable Henriette Delille (1813–1862), the daughter of a white man and mixed-race woman who lived in a common-law relationship, founded the Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans, and she and these women attended to the needs of slaves and poor free Blacks.

- Servant of God Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange (ca. 1794–1882), a former slave from Cuba, founded and served as the first superior general of the Oblate Sisters of Providence in Baltimore. She founded the order so that Black women would have a means by which to enter religious life and to educate Black children.

- Servant of God Father Augustus Tolton (1854–1897) was the first Black US priest. He studied in Rome because no US seminary would admit him. His ministry in Quincy, Illinois drew congregants from the nearby white parish. He eventually moved to Chicago, where he founded the city’s first Black parish.

- Servant of God Julia Greeley, born into slavery, was known for collecting food and other goods for the poor, and was revered as “Denver’s Angel of Charity,” despite her own poverty. A slave master, in the course of beating her mother, caught Julia’s right eye with his whip and destroyed it. Freed by Missouri’s Emancipation Act in 1865, Julia served white families but spent everything she had assisting poor families. Julia entered the Church in 1880 and joined the Secular Franciscan Order in 1901.

These five candidates’ lives were made all the more difficult because in addition to the trauma of racism, they faced religious exclusion; Catholics of all ethnicities were initially a feared and despised immigrant population in the United States. This changed after World War II.

Symbolically, the culmination of “Americanization” among US white Catholics occurred when John F. Kennedy became president in 1960. But the history of Black Catholics involves a more complicated tale that’s similar to those of Catholics of Latin American and Asian descent. This initiative to recognize Black Catholic leaders who helped to transform what it meant to be both Black and Catholic is praiseworthy, regardless how long it takes to attain the title of saint.—Jim Schaffer