May 10, 2018; Orlando Sun Sentinel

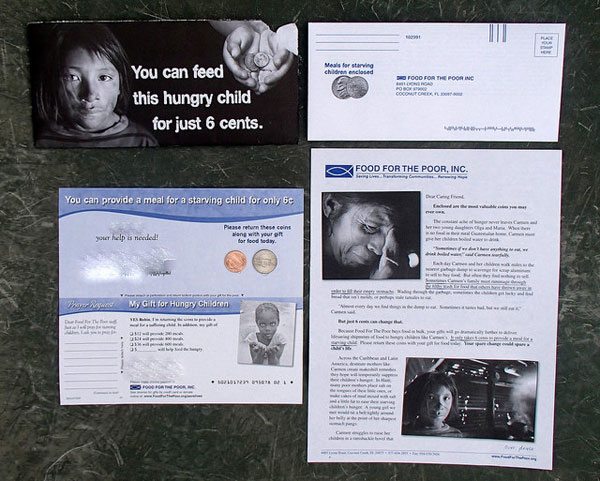

A familiar pattern of “creative” nonprofit accounting was referenced in an article yesterday in the Orlando Sun Sentinel which reported that a Florida organization called Food for the Poor has been ordered to cease and desist by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, who is also looking to have the organization’s registration revoked for overreporting its revenue.

Why would a nonprofit want to do such a thing, you might ask? It makes them look larger and more legitimate, and it makes their overhead ratios look better. The way this is done is by taking in in-kind gifts and overvaluing them. This is a pattern that seems to appear most often in organizations donating abroad, something NPQ and others have been reporting on since 2012.

In Food for the Poor’s case, the in-kind donations are largely pharmaceuticals, which made up 54–71 percent of its revenue over the three-year period between 2012 and 2015. (In 2015, it listed its income at almost $1.6 billion, according to Becerra.) These particular pharmaceuticals were prohibited from being sold in the United States because they are close to their expiration dates; even in the countries to which they were shipped, they would be sold at a fraction of their original price. This, Becerra asserts, means that the value of the donation must be figured according to those foreign market prices rather than the “very high US market prices.”

To illustrate the difference, Becerra cited a shipment of the cholesterol medication Simvastatin to Nicaragua in 2012. It could have been bought there for $5,000, but the charity valued it at $924,671.

“The appropriate international market prices for most of the pharmaceuticals at issue were a fraction of the values Food for the Poor reported,” the order says. “Had Food for the Poor used appropriate international market prices to value its pharmaceutical donations, its reported revenue and program expense figures would have been markedly decreased.”

Why should Becerra care about what this Florida organization was doing? Because, according to the order, “From 2012 through 2015, Food for the Poor conducted substantial charitable solicitation activity in California, collecting over $38,598,000 in over 727,700 donations from California donors.”

Becerra’s order also cites the charity for claiming that it passed along 95 percent of all donations to poor people. This, according to the order, was false, with the real proportion being far less.

The 95 Percent Statement was deceptive because it included both cash and noncash donations. But noncash donations, including Food for the Poor’s overvalued pharmaceuticals, did not pay for any overhead or fundraising; only the cash donations did. The 95 Percent Statement implies that 95 percent of cash and noncash donations will be used for direct aid and only a mere 5 percent of donations will be used for fundraising and salaries. That was false. Food for the Poor used only 66.2 percent of cash donations for direct aid in 2013.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi has not yet commented on the case, though the order was filed on March 28th and Florida appears to be home to too many such endeavors. Remember, if you will, that Florida was home to the very similar story of the bizarre US Navy Veterans Association, which finally ended with the perpetrator’s anonymous arrest in Ohio. But in the state of Florida, charities and nonprofits are, oddly enough, regulated by the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Dedicated NPQ readers may remember a spate of cases like this one gaining publicity in 2012 and 2013 when Forbes did a series on the deceptive practice of overvaluing in kind donations, which is often exacerbated by daisy-chaining the inflated value of donations from one charity to another. This is described here:

Overvaluation is a serious problem in overseas relief, a field in which medications, clothing, and other donated goods are a big part of revenue. Overvaluing gives donors the impression that the organization is both bigger and more efficient than it is. It is often associated with “daisy chaining,” the practice in which donations are transferred from one organization to another in order to make the volume of activity appear larger than it is. This practice can be obscured by the fact that, in many cases, it may legitimately require a number of nonprofits to collect and distribute goods internationally.

These practices are so common that there are serving groups set up to help aid organizations do this. As we reported in 2014:

Located in South Carolina, Charity Services International acts as an intermediary for other nonprofits, accumulating donated goods from medicine to candy, coordinating shipping abroad, and filling out the reports required by a nonprofit’s auditor and the IRS. In 2010 alone, Charity Services coordinated approximately 50 shipments valued at almost $110 million, and most of it went to Guatemala.

Despite their centrality to the practice, Roy Tidwell, the owner and president of Charity Services International, described their facilitation as “logistics” services. “Each charity has the responsibility to assign value to donations,” Tidwell said.

But Charity Services was clear about its intent; according to the Tampa Bay Times, its website from 2010 advertised, “Reduce fundraising percentages by booking large gift values for a low service fee.” (Currently, the Charity Services’ website repeats in several places that it “does not provide any fundraising services or fundraising counsel. No services or information mentioned on this site should be considered fundraising, accounting or legal advice or counsel in any manner.”)

And they did, in fact, ship goods to Guatemala on behalf of its charity clients in 2010, according to customs documents. But apparently no one checks what is in the shipment—“not even the charity that claims credit for the donated goods. They rely on inventory statements provided by Charity Services.”

On the far end of such practices are the cases where the gifts don’t make it to any documentable destination, as in the cases investigated by a combination of the Tampa Bay Times, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and CNN in 2014. Part of the pattern is that the groups using this service also rely on professional solicitors who do the kind of mass solicitations that have themselves so often been called to account by regulators for deceptive practices, practices that eat up the majority of the donated funds and, at times, practices that abusively target elderly givers.—Ruth McCambridge