September 19, 2015; Daily Herald (Chicago, IL)

Yesterday, NPQ published a newswire on the profiteering happening in pharmaceutical pricing. For us, this serves as an entry into a set of complex issues that nonprofits are often in some way involved in, either as complicit partners or in dealing with the outcomes. In this case, many nonprofits dealing with community health, substance abuse, and general community well-being will have taken part to some extent in the development of a community response to opioid abuse.

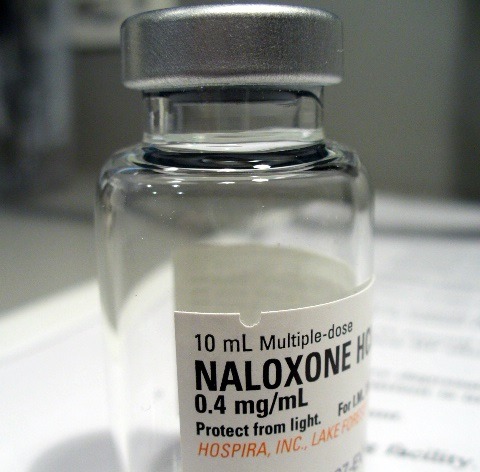

More and more first responders around the United States are already carrying naloxone, or Narcan, a medication that has been credited with preventing many deaths by restarting the breathing of overdose victims. Baltimore, in fact, has extended naloxone training to drug users themselves and to their families and friends. Approximately 4400 people have been trained, which is fourfold the number trained in 2014. But as the use of naloxone has increased, the price has not gone down, but up—from $10 to $20 a dose in February to as much as $40 in July. The pricing is also not consistent from place to place, with some locales reporting prices per dose that are far higher.

Amphastar Pharmaceuticals makes the most widely used version of naloxone because it can be administered intranasally. Maryland Rep. Elijah Cummings, ranking member of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, faults the company for its pricing. “When drug companies increase their prices and charge exorbitant rates, they decrease the access to the drug,” Cummings said this summer. “There’s something awfully wrong with that picture.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As with many other medications whose prices have skyrocketed recently, naloxone isn’t a new drug, having first been approved by the FDA 44 years ago. As recently as ten years ago, the price per dose was $10. Back then, the market was much smaller, confined to hospital settings for the most part. Now, there are 40 states and counting attempting to use it more broadly to curtain the wave of opioid overdoses that has been plaguing many communities. In Illinois, for instance, the legislature has just cleared the way for school nurses to make use of it. Schools in Pennsylvania and New York are stocking it, too.

In Massachusetts, where 1200 people died of heroin overdoses this past year, Attorney General Maura Healey recently announced an agreement with Amphastar requiring it to pay $325,000 to help offset the costs of the drug, which varied across the state. “We purchased 900 doses of naloxone to provide to all of our police and fire departments in March of 2014, and we paid roughly $22 a dose,” Norfolk County District Attorney Michael W. Morrissey said. “Some of our municipalities were using those doses very quickly. When we offered grants to help replenish those supplies, we saw that the prices were inconsistent and rising, with Walpole paying $37.50 per dose, Randolph paying $39 per dose, and then Needham and Wrentham paying $66.89 for the same dose. We knew something was wrong with this picture.”

Competitors are entering the Naloxone market, but they are now waiting for FDA approval—and even after, that they may decide to join the rapidly expanding market as-is rather than compete on price. Is the answer to the crisis individual, state-by-state negotiations, or is there a larger fix needed that incorporates unreasonable price increases in drugs more generally?

Some presidential candidates are already proposing new approaches to the problem, We will talk about those in an upcoming newswire.—Ruth McCambridge