December 3, 2016; New York Times

An opinion piece in the New York Times Sunday Review reveals the sentiments of a Mr. Bart Somers. Somers is the mayor of Mechelen, a small town in the Flemish region of northern Belgium that lies smack in the middle of the stretch between Brussels and the port city of Antwerp. This stretch is notoriously “responsible for eight percent of all Europeans who have left to fight in Syria and Iraq.” However, the thrice-elected mayor says that despite the Muslim background of 20 percent of his constituents, none of these people came from Mechelen. He credits this to Mechelen’s welcoming refugee initiatives and policies:

There are mayors who said that if people of their city go and fight in Syria, they hope they will die there. I say the opposite. I have to do everything to prevent young people going and throwing away their lives there, because they are kids of my town, they are children of Mechelen.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

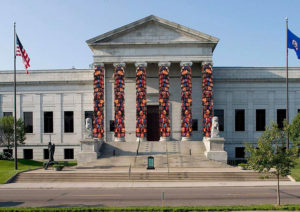

Mechelen is small, about 85,000 people, and described as a “city of cobbled streets, Gothic architecture, and a UNESCO-listed cathedral.” Gazing up at the cathedral’s bell tower is a 20-foot-high inflatable effigy of a refugee created by the Belgian artists’ collective called Schellekens & Peleman. The nameless figure in an orange life vest crouches on a rooftop, embracing his knees tightly in a pose that “reflects the universality of his plight.” That’s said even considering that local Europeans may see the figure more as part of a “nameless mass threatening their way of life,” a sentiment reflective of the way many view the refugees and migrants arriving in their cities. But, as the N.Y. Times puts it, “things are different” in Mechelen.

Somers is looking to bridge differences between the city’s natives and the growing number of arriving refugees. The art piece is described as “one of the more abstract of several initiatives” meant to encourage interaction between locals and the new arrivals. The piece is meant to function as a vehicle for “stripping away the anonymity” of the figure to foster cooperation and understanding. This appears more important than ever; host countries face the threat of terrorist attack and right-wing parties stoke such fears for electoral gain.

European communities are said to be passing the point of addressing the vulnerable population’s immediate needs, “like emergency housing, food and medical care.” They must now address broader challenges of inclusion as these asylum-seekers rebuild their lives in new societies. Such adjustment is never really one-sided. As Gabriella De Francesco, a former teacher who now works with Mechelen’s refugee integration strategy, says, “People are afraid of the unknown.” This is a core focus in Mechelen’s strategies. For instance, Somers hosted an “open day” for the new refugee center he volunteered to open in the city. There, locals could familiarize themselves with the center and learn more about the local scout group’s “buddy” program that “pairs new arrivals with a local.” There were also opportunities to spend a day at the adult learning center that teaches the Dutch language and local cultural norms to the newcomers. A small dual-language-learning labor market project has also been piloted, wherein refugees learn language skills for a few hours over lunch and then return to work with a locally subsidized cleaning company. So as not to neglect the city’s native population, all residents of Mechelen can access such social policies—even the buddy and cultural norm programs.

Other countries may have similar initiatives, but Mechelen’s advocates work to deter more “out of sight, out of mind” approaches and policies that promote barriers to broader access. (For instance, even though many refugees are granted work visas, the reality is that employers will often not hire temporary residents.) Meanwhile, as a 27-year-old mother of two from Afghanistan told a reporter, “In Afghanistan, women can’t go outside, but in Belgium I can go outside. Here my children can go to school. European people, and me, an Afghan—we are all the same.”—Noreen Ohlrich