Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during Nov/Dec 2004, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

Over the past 17 years, I’ve been the founder and executive director at two nonprofit organizations. One of the key challenges that I’ve faced at both of these agencies has been creating an effective board structure. Because I was a founder at each organization, the boards tended toward being more “hands-off,” generally deferring to my lead.

While this has had its benefits, I have also been aware that to create a sustainable organization, it is important to develop a structure that affords the board greater opportunities for input, vision, and governance. This article is an attempt to describe our experiment at Sports4Kids with an alternative structure that we have named the Seasonal Board.

Sports4Kids is a grassroots nonprofit organization bringing structured sports and recreation programming to more than 20,000 children in 65 low-income, underperforming Bay Area elementary schools. Founded in 1996, Sports4Kids gives kids the chance to play in an environment designed to encourage participation and alleviate conflict.

LOOKING FOR ALTERNATIVES

In the fall of 2001, while preparing to teach a college level course on starting a nonprofit organization, I was reading Kim Klein’s book, Fundraising for the Long Haul. Her chapter on creating an effective board and, in particular, the importance of the committee structure, rang true for me. In describing alternative board structures, Klein writes of the ad hoc committee structure:

Molly spoke of the frustration of being a part of a board

that felt like a rubber stamp, alternating with feeling guilty

for not being able to do more.

In this alternative, the board can be small or very large, but the work of the organization is done by a number of committees made up of board and non-board members, possibly including staff. Each committee has a lot of autonomy abilities. They come together to complete a task and then they dissolve into another committee. The full board meets no more than quarterly to decide what committees will exist for the next period of time and who will be on them. Once a year, the board and staff, in a one or two-day retreat, prepare an extensive work plan for the year.

Generally, this structure calls for some kind of oversight committee, which would traditionally be the executive committee. These ad hoc committees should not be limited to the traditional committee names and functions, such as Nominating, Personnel, Finance and so on. You can have Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall committees, with five to seven people taking full board responsibility for one quarter of the year. The rest of the board participates as needed. This works well for the very busy people we tend to attract to our boards — they will carve out the time for a short period but aren’t able to sustain that level of commitment for a whole year.

A month later I was having breakfast with one of my board members, Molly. Molly wanted to discuss her concerns around her involvement on the board and to let me know that she was considering stepping down. She started by acknowledging the contradictory nature of her concerns, and yet it came down to a complaint that I had heard in various forms throughout the year — a combination of “I’d really like my involvement on the board to be more substantive, more meaningful” and “I really don’t have the time to make the kind of commitment that I’d like.” Molly spoke of the frustration of being a part of a board that felt like a rubber stamp, alternating with feeling guilty for not being able to do more.

My conversation with Molly and other board members reinforced for me the value of Kim’s suggestion about ad hoc, quarterly committees stepping into more involved activities for a short period of time. The structure that evolved for Sports4Kids was four seasonal committees — literally Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall.

HOW IT WORKS

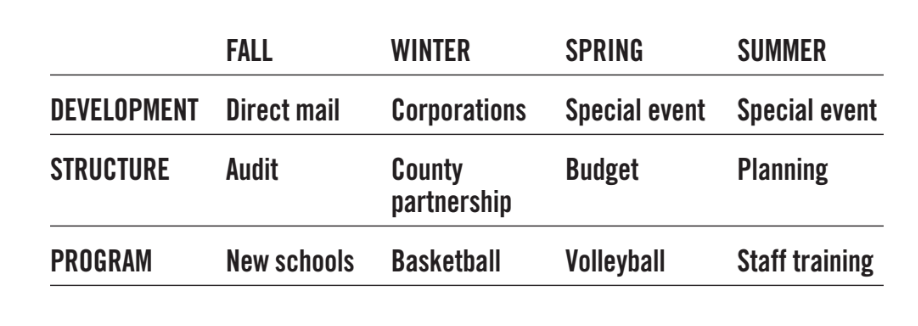

Each committee takes on three issues or areas to pay close attention to during its term: a development issue, a governance or structure issue, and a program area. In the realm of program, the work of the board was to become more familiar with an aspect of the agency so they could be more informed when representing the agency in the larger world. From the outset it was explicit that the board’s involvement in program was to inform governance and development issues, not to micro-manage operating decisions. We’ve had good results: board members have invariably reported being inspired by their program visits and left with a more tangible grasp on our mission. The first year’s meeting themes broke down as follows:

The amount and type of work that each committee put into each area varied with the subject and the participants. For example, the Winter team that focused on establishing county partnerships worked with me to schedule meetings with the department heads of assorted county agencies — Health, the County Office of Education and Probation, among others — and attended those meetings with me to familiarize county staff with our efforts and explore opportunities for collaboration.

In addressing corporations, the Winter team created a list of contacts at local businesses and made contacts with corporations to identify corporate sponsors for our golf tournament. Ultimately the corporate committee recommended creating a new signature event because the golf tournament market is so saturated. As a result, we created the Sports4Kids Corporate Kickball Tournament, with ten corporations fielding teams of 10 grown-ups playing in a day-long tournament on Treasure Island.

The amount of leadership assumed in each area seemed to reflect both board member personalities and comfort with the topic. For example, our treasurer worked easily with our auditor and independently of me set up meetings and discussed their findings. Similarly, the committee that worked on the Special Event — a wine tasting — did virtually all the work without asking anything of staff until the day of the event.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In the direct mail project, Fall committee members contacted all of the board members to gather individual mailing lists and then assisted with the actual mailing — handwriting notes, and so forth.

On the other hand, encouraging the board to observe programs in action has always required a high degree of staff cajoling and going through the budget so that the board has a strong understanding; this requires a lot of staff involvement. While the need for cajoling continues under the new system, the focus of each season lends a structure that has allowed the board to take more responsibility for its own course of action.

COMMITTEE COMPOSITION

Since the board has between 10 and 15 members, we decided to have three board members on each seasonal committee, enhanced by one to three non-board members. We use the non-board committee slots both to beef up the work the committee can accomplish and as a reciprocal vetting process for new board members: potential board members get a sense of us and we of them.

On their side, non-board committee members tend to be involved either because they bring some expertise to an issue or task or because they want a “board-lite” experience. For example, in the season when the board looked at the implications of becoming an AmeriCorps program, we invited a former AmeriCorps program director to serve on the committee to assist with understanding and planning. Others often become involved to work on a specific fundraising event, such as the wine tasting or our corporate kickball tournament.

GREATER ENTHUSIASM ALL AROUND

In transitioning the entire board from monthly to quarterly meetings, we decided to keep the Fall, Winter, and Spring meetings at two hours but to change the Summer meeting to a longer (5-hour), retreat-like format.

With the switch to the quarterly meetings, I found that my enthusiasm for creating more engaging meetings — bringing in guest speakers, better food, and more forethought in creating opportunities for input — increased markedly. Moreover, the seasonal committee members took a more active role in setting agendas and presenting information. For example, the Spring committee, which reviews the proposed budget, now leads the budget discussion at the Spring meeting, fielding questions about specific line items and encouraging a more significant level of understanding and ownership.

Board meeting attendance at the quarterly meetings also improved dramatically and the level of dialogue has stepped up. There are probably two reasons for this: the greater involvement of board members at the committee level, and the presence of non-board members at the meetings. Because the non-board committee members are invited to the board meetings both before and after the season in which they serve, there are between two and six non-voting community members participating in discussions and generally increasing the sense of enthusiasm and possibility.

REASONS FOR SUCCESS

In many ways, the new board structure has invigorated our board and been quite successful. There seem to be a number of reasons for this success. On one level, the very new-ness of the structure engaged folks. More important, though, board members feel that the new structure has brought more meaty tasks to the board — more concrete opportunities for them to think big thoughts and have meaningful input in the direction of the agency. This is probably a result, too, of the expectation that board members will work hard for a finite period of time, then take a back seat for the other quarters of the year.

Board members feel that the new structure has brought more meaty

tasks to the board — more concrete opportunities for them to think big

thoughts and have meaningful input in the direction of the agency.

Even with this new enthusiasm, the board is still hesitant in initiating some tasks; this may be a lingering result of the natural relationship between founders and boards combined with the need for staff to nurture leadership in the board.

CHALLENGES

The transition hasn’t been without challenges. There have been seasons that, for an assortment of reasons — scheduling, inadequate staff support, poor theme selection — board work just never happened. But the board has responded creatively, taking more leadership in determining the topics for the current year at our annual retreat and committing in advance to different seasons based on topic interest. The board has also shown greater leadership in identifying and recruiting outside committee members.

It has become clear that the board also needs a standing executive committee that can act quickly and with a higher degree of authority. We established such a committee, made up of the Board Chair, Treasurer and Secretary, last year, the third year of our seasonal structure.

At this year’s annual retreat, the board agreed unanimously to continue with the Seasonal Committee structure. The board continues to wrestle with the issue of assuming leadership for its own direction and the struggle around fundraising continues, though the addition of a staff person dedicated to corporate and individual giving with an emphasis on events planning has created a better structure for plugging in board members.

WORTH A TRY

The Seasonal Committee structure has been an effective approach for Sports4Kids because it shook things up and compelled us to look at how the volunteers serving on the board might best contribute to the organization. Moreover, trying a new model opened up the process of involvement for both staff and board members and allowed us to bring some creativity to an aspect of our agency that hadn’t been functioning effectively.

Finally, it seems that being part of something new has the potential to inspire greater thoughtfulness and leadership — two hallmarks of an effective board. Based on our experience, I would encourage others to take a fresh look at the way your boards function and encourage board members to consider alternative structures to give greater meaning to their contributions of time and effort.