Editors’ note: The Grassroots Fundraising Journal (GFJ), in publication from 1984 through 2020, is now being archived on the Nonprofit Quarterly’s website. The 600+ articles that comprise The Grassroots Fundraising Journal are used widely by fundraising professionals and volunteers, professors in university courses on nonprofit management, seasoned practitioners, and people brand new to the ideas and concepts presented there. This article as it appears here is from the winter 2020 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly magazine, with edits. (It was first published in print in December 2000, was published online by the Nonprofit Quarterly on May 5, 2020, with some updates.)

Three True Stories Told to Me by Recent Clients

- Last year, the board member of a large social services agency serving teens decided to ask all her neighbors for a donation. She wrote a letter in which she made an eloquent case for the agency, already well known in the community, and asked each family to give $10. She had hand-delivered 200 of these letters, with a return envelope. The letter raised $1,200 from eighteen households. Two neighbors gave $250 each, and two others gave $100. Only one person gave $10. The rest gave $35 or $50. Five people replied that they were not giving because they gave elsewhere or were unable to give right now. This board member plans to do exactly the same thing this year—hand deliver two hundred letters asking for $10.

- A program advocating for the rights of prisoners held an open house, at which the development director met a woman who said she would like to make a “significant donation” to the work of this group. This woman had not contributed before and said she had only recently learned of this group and was very impressed with their work. The development director arranged to meet her for coffee the following week. In the meantime, the development director found out that this woman gives thousands of dollars to a variety of social justice groups and is the “biggest donor” to a large public interest law firm. The development director decides to ask her for $500.

- A dentist learned that one of his patients had donated $10,000 to a land conservation effort in his state. Although the patient has been using this dentist for a long time, the two know very little about each other. The dentist is on the board of a struggling repertory theater and decides to ask his patient for $10,000 for the theater. He assumes the patient gives to the land conservancy because he is community minded, and that he would therefore also be interested in the theater.

Good Idea, Wrong Request

All three stories describe good fundraisers. They are thinking about their group and who might give. They are willing to do the work required to get the gift. Many organizations would rightly be thrilled to have any of these people as board members.

However, without seeming unduly harsh, I would say that in each of these cases, the decision made by the solicitor was wrong, wrong, wrong. Their problems are not unusual; determining exactly who is a prospect and how much to ask them for has waylaid many a solicitation. Fortunately, there are some simple guidelines that can make the process a lot easier. By discussing what approach each solicitor in the stories should have taken, we can illustrate these guidelines.

In the first story, the board member’s first effort—hand delivering 200 letters to her neighbors—is a great idea, and one that almost anyone could do. It is especially a good idea when the organization being solicited for is not very controversial and is fairly well known in the community. The board member’s decision to ask for $10 the first time is fine, although the response shows that if she uses this method again, she can start with a higher amount, such as $25, without losing anyone. She gets an almost 10 percent response from her letter—which is excellent, compared to direct mail, for example, where we would expect a one percent response, and almost as good as a door-to-door canvass, from which we would expect a 12 to 15 percent response. The neighbors who respond demonstrate that they like her, and they seem to like this organization—particularly those who give $100 and $250.

The board member tells me that her decision to go back to the same group with the same request is predicated on not wanting to make people feel like they have to give a big gift again, and to see if some of the neighbors who didn’t give might change their minds and give this year. I explain to her that the people who gave larger gifts will be surprised to receive such a letter again, and some may even be hurt if she does not acknowledge their previous gift and ask them to repeat it. If she asks for $10 from a $250 donor, without meaning to she is telling that person, “I want $10, try to get that straight this year.”

After speaking with me, she decides to write personal letters to her eighteen donors, asking for renewals. She will follow up with phone calls or visits, depending on her relationships with these people. She will again take a letter around to the rest of the neighborhood, this time requesting $15 to $35. She is prepared for a much lower response this time but wants to keep the organization in her neighbors’ minds. All eighteen of her donors renew. One person who had given $100 gives $200, and the rest give what they had given previously. Ten neighbors who had not given last year give a total of $300, including gifts from two who had not been able to give the year before.

In the second story, a donor who gives gifts in the $1,000 to $10,000 range says she wishes to make a “significant gift” to an organization. The development director does not want to alienate this person by asking for too much. I explain that having said “significant gift,” the prospect cannot really be shocked by being asked for a large amount, even an amount that may be more than she had in mind. The development director knows that this prospect is comfortable with giving large gifts. Of course, we don’t know what she means by “significant,” but she probably means more than $500. The development director decides to show her the organization’s gift range chart, which calls for a lead gift of $15,000, three gifts at $10,000, four gifts at $5,000, and so on. The purpose of sharing this information will be to establish a giving range for this donor to this group. I suggest asking the prospect if she can give in the “$2,500 to $5,000 range.” Skeptical but willing, the development director does just that, and receives a pledge of $5,000.

The third story is about an enthusiastic but not terribly sensible board member. I ask him if he knows anything about this patient besides his dental history and his gift to the land conservancy. He knows he has two children and is a partner in a small business, but he does not know the nature of the business. To his knowledge, this prospect has never come to his theater. “You can’t start by asking him for a gift that is the same size as his biggest gift to his favorite charity,” I explain. “You have no evidence that he believes in supporting the arts or has interest in theater.”

I suggest starting with a conversation about theater and the dentist’s role in the theater. If the patient shows interest, the dentist should offer him two free tickets to a play. If the patient takes them, the dentist should try to find out if he actually goes to the show. Only after a few more indications of interest will it be appropriate to ask for a gift, and even then, starting with a small request by mail may be more appropriate.

When the dentist next sees this patient, he skips having a conversation about the theater and just offers him two free tickets. The prospect seems touched and thanks him, but says, “Don’t waste these on me. I am not a theater person. I never even go to the movies or watch TV.” The dentist reports to me that he was relieved that he pursued his patient less directly than he had originally planned.

Who Is a Prospect? Three Guidelines

Although each of these stories is different, they raise many of the same issues. To begin with, it is important to be clear on who is and who is not a prospect. This is the first guideline to follow.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A prospect is someone who we know gives money—and have an idea of how much money they give and what kinds of causes they support. We know these things because we know the individual personally. Certainly, we can approach someone without having all this information, but our chances of getting a gift are diminished, and we can sometimes do damage to a relationship by not paying attention to what we don’t know.

If you hand deliver a letter to all your neighbors asking for money, you need to know that some of them won’t respond, because they don’t give away money at all (about 30 percent of adults don’t make any charitable contributions). Another group won’t give because they already have a set list of organizations that they support and aren’t going to add more. Another cross-section won’t give because they don’t believe in or care about the cause. Finally, some people won’t give because they don’t respond to mail appeals, no matter how personally they arrive.

In our first story, the board member probably got a 50 percent response from the people in her neighborhood who were truly prospects. Out of her 200 neighbors, sixty (30 percent) are not givers. Upward of 30 percent more either don’t give by mail or have already decided which groups they support and won’t add more. Even though the group she represents is popular and well respected, at least 10 percent of her neighbors either don’t care about it or think that because it is popular it doesn’t need their money. This leaves about sixty households that may be prospects; after two appeals, she has gifts—some of them large—from twenty-eight of them. As readers of the Journal will recall, a 50 percent rate of “yes” is what we expect from a personal solicitation.

A second guideline in approaching prospects is one that we don’t talk about nearly enough: the solicitor needs to be on a level playing field with the prospect. For example, it is not good to solicit people who work for you. No matter how friendly everybody is, there is an unequal relationship between supervisor and worker, and a good employer will never want an employee to feel coerced into giving. The same is true for using confidential information as a background for soliciting people. This makes it difficult for accountants to solicit clients, for example. They know which clients give away money, how much, and often to what. But they learned that in a setting that the client has reason to believe is confidential. If a client asks for advice about what kind of charities to support, certainly an accountant could then talk about his or her favorite group. Lawyers, therapists, financial planners, and the like are in similar positions with their clients. Medical professionals are in a more fuzzy area here, but the relationship is often one in which the patient feels vulnerable or exposed in some way, and medical professionals should be careful. Again, unless you are also a friend of your clients, you will want to think carefully before soliciting your client list.

I have, however, seen instances in which people solicited clients very successfully. For example, the owner of a garden store that specializes in native plants, organic fertilizer, alternatives to pesticides, and so on, is on the board of a local environmental organization. In a letter to his mailing list, he wrote that he knew his customers shared his values and would want to know about this group if they didn’t already. He is on a level playing field with the customers that have signed up to be on his mailing list: he knows little or nothing about them from his professional dealings, except that they shop at his store. His letter was very successful, raising almost $3,000 from seventy people from a mailing list of five hundred, and many customers thanked him for introducing them to the organization. He is, of course, as in the previous example, writing to some people who are not givers and to some who have already established commitments.

Third, once we know that a person supports certain kinds of causes, we have to ask ourselves how close our organization is to the cause the person supports. Certainly, many people who support conservation also go to the theater, so our dentist wasn’t wrong to think of his patient as a potential donor, but he needed more direct evidence that this person was also interested in the arts. The patient made it clear that he is not interested in theater, at least as a member of the audience. It is true that some people support community organizations without ever using them, such as parks, libraries, museums, and theaters, to say nothing of service projects such as shelters or food banks, but the dentist has no information that his patient falls into that category either. He does not even know why this person supports the land conservancy. Besides the patient’s dental history, the dentist doesn’t know much more about him than he might find in the newspaper. He does not have a relationship with this person that will allow him to pursue any kind of gift at this time.

How Much to Ask For

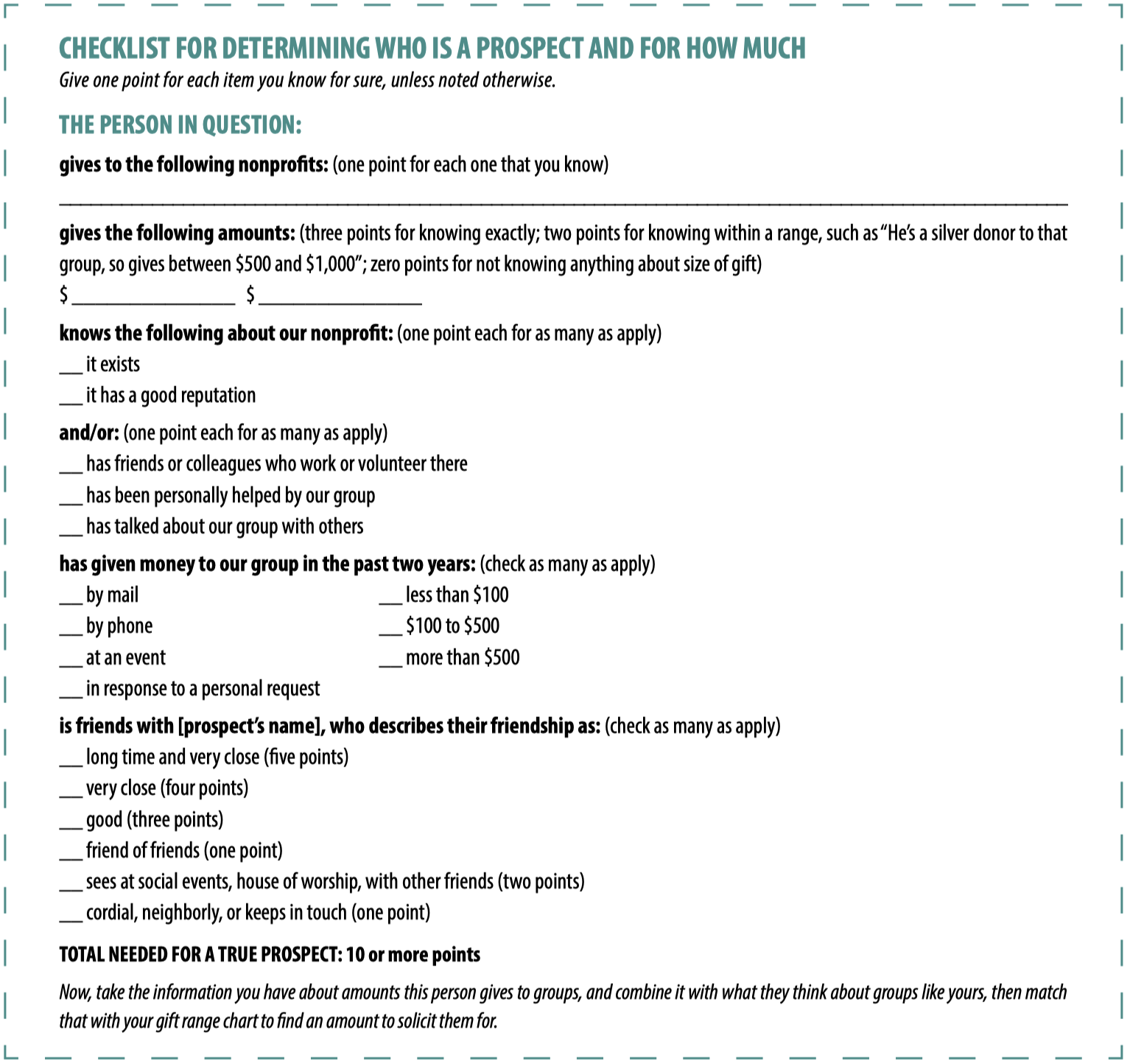

Once we have established that the people we want to approach are, in fact, prospects—they have the ability to make a gift, they believe in the cause, and we know them, like them, and they like us—then we have to ask, “What size gift shall we request?”

Here we examine where the prospect is in relation to our group. A long-time donor is asked for a different amount than a first-time donor. If the person has a long history of giving to organizations similar to yours, you will probably start with a different amount than for someone who has only recently become interested in your issue. And, of course, we take a clue from the prospect: if she says, “I want to make a significant gift,” we feel freer to ask for a large amount than if we are the ones initiating the conversation. Finally, we look at our fundraising goals and our gift range chart, so that we can justify the amount we are asking for as being one of the many gifts we need.

Donors should not be asked for a certain size gift just because that is the same size gift that they gave somewhere else or because we heard that they “have money.” Once a person has made a gift of any size, we have a place from which to start negotiating for another gift. “Can you give again?,” “Can you double this gift?,” “Would you consider giving this much every month?,” and so on, depending on our relationship with the donor.

In the end, you don’t know how much someone can give—and even if you knew everything about their financial situation, you still wouldn’t know how much they might give, because that number will depend on their mood, on how generous they feel, on what other experiences with money they have had that day. Your job is to be as accurate and as respectful as you can. Their job is to say yes, no, or maybe.