This article is from NPQ’s fall 2015 edition, “Making Things Work: Considerations in Nonprofit Strategy.” Subscribe Today

As social entrepreneurs around the world create new organizations to solve emerging public problems, they do so drawing on a broad range of organizational forms, ranging from the traditional nonprofit form to the classic business corporate form—and, most recently, a whole host of hybrid forms located between these poles. Sometimes, the initial institutional auspice works well for the entrepreneur, and constitutes a firm foundation on which to build the organization. Often, however, the question of which form to adopt generates substantial stress inside the organization, because the reasons one form would be preferred over another are not well understood. The complexity of this decision is exacerbated by the continually blurring distinctions between for-profit and nonprofit organizations around the world. For example, more and more nonprofit organizations are integrating earned income models—with sales, revenues, and profits—into their nonprofit activities. At the same time, the socially oriented business attempts to integrate selflessness and social impact into its for-profit activities.

As more nonprofits behave like businesses and more businesses uphold social values, it becomes less obvious why a social entrepreneur would adopt one structure over another. Indeed, the characteristics that have historically described the differences between organizational types—for example, whether they have a community-based board or a board of private owners, or whether they have primarily volunteers or paid staff—are not in themselves causal factors; instead, those differences are secondary consequences of the decision to adopt one organizational type over another. At the same time, even those distinctions between organizations are becoming less absolute. Similarly, as social entrepreneurs seek to enjoy the best of both worlds, more and more are looking toward hybrid models, in which the organization embodies traits of both traditional for-profit and nonprofit organizations. This hybrid zone, now occupying the majority of the social enterprise spectrum, is extremely ambiguous and notoriously difficult for social entrepreneurs to navigate.

As a result, many new organizations experiment with their sectoral type, at various times changing from nonprofit to for-profit or some type of hybrid model. These iterations are a drain on resources, because the changes in organizational type require reworking several items, including financial models, partnership agreements, and operational systems. Consequently, the choice of which organizational form is most appropriate for a given innovation is a critical element for the maximizing of social and financial returns.

A fresh focus on the key drivers of appropriate sector selection would be valuable both as a diagnostic tool for assessing choices made by current entrepreneurs and also as a predictive model that could explain long-term enterprise effectiveness and sustainability. Building on foundation theory and early conceptual models, this article addresses the choice between nonprofit, for-profit, and hybrid forms, and offers a framework for deciding which one best suits the social entrepreneur. Rather than focusing on the factual differences among organizational forms, our model argues that sector selection should depend on three key assessments: the nature of the social value proposition, the environment in which the enterprise will operate, and the personal traits of the entrepreneur—each of which points in part toward a solution to the challenge of appropriate selection of organizational form. The model identifies the possible outcomes as being one of five discrete organizational types: the pure nonprofit, the nonprofit with earned income, the hybrid, the business with a social mission, and the pure for-profit organization. To make this determination, the model employs a line of questioning that cumulatively yields a final recommendation as to which organizational type will be the best fit for the social entrepreneur.

Existing Literature

The challenge of developing a normative theory of sector selection for social entrepreneurs is rooted in an extensive body of literature that cuts across the nature of organizational forms to the drivers of entrepreneurial behavior. For decades, researchers have sought to isolate the defining features of nonprofit organizations while recognizing that the rise of hybrid forms adds complexity to the old binary thinking. At the same time, increasing research has been conducted on the distinctive traits of different kinds of entrepreneurs and the consequent impact of personality type on an organization’s functioning in both the business and nonprofit sector. However, none of these attempts at description and theory building have focused on the precise issue of sector selection by social entrepreneurs.

Descriptive Literature on Nonprofit Form

In the first wave of research on nonprofit organizations, during the 1970s and ’80s, there was a concerted attempt to determine the distinctive and identifying features of nonprofit organizations. This work focused on the functional attributes of nonprofit organizations and then held these up for comparison with for-profit and government sector organizations. The goal of scholars like Lester Salamon, Michael O’Neill, Peter Dobkin Hall, Burton Weisbrod, Henry Hansmann, and others was to isolate the features that constituted the core identity of nonprofit organizations. Often this came down to the nonprofit organization’s nondistribution constraint, private nature, self-governing/ownerless character, and the variety of stakeholders asserting claims over the nonprofits.

Sometimes, the descriptive work related to nonprofit forms was done in a comparative format. The most common approach to this work is a table featuring nonprofit, business, and government on one axis, and key traits and attributes on the other. With a table like that, the differences across sectors become clear. This first wave of descriptive research helped us to understand the attributes of organizations from different sectors, but it provided no guidance on what might lead to choosing one form over another. It therefore failed to contribute substantially to a normative theory of sector selection.

The idea of a social enterprise spectrum represented a major breakthrough in descriptive work about the sectors in that it evolved the traditional sectoral triad into a more flexible continuum of organizational types. As defined by J. Gregory Dees, the social enterprise spectrum runs from organizations that are entirely commercial, for-profit, and market driven to those that are entirely charitable, donative, and voluntary.1 By arguing for a continuum leading from purely philanthropic to entirely commercial—and with a middle ground full of hybrid forms—the spectrum usefully defeated the idea that precise and immutable boundaries separated the world of organizational forms. Entrepreneurs of all kinds will choose activities and organizations that fit somewhere along this spectrum.

When the idea of a social enterprise spectrum was first presented, in 1998, it was a breakthrough concept that challenged our understanding of the nature of sectors and the purity of organizational forms. As the idea has evolved, the worlds of research and practice have learned to appreciate the features of organizations lying on the extremes as well as the center of the spectrum. Over the years, the distinguishing characteristics of nonprofit, for-profit, and hybrid forms have been delineated frequently in tables and grids, often contrasting goals, governance, funding, workforce, culture, and other dimensions. This descriptive work has deepened our understanding of the choices and trade-offs faced by social entrepreneurs, but it has not provided a clear set of decision rules that can drive sector selection.

Theoretical Literature on the Nonprofit Entrepreneur

In the business world, entrepreneurship is an old and trusted idea and practice that has spawned voluminous literature. Entrepreneurship is an appealing idea because it speaks to the desire of many individuals to take control of their lives and financial futures. Still, definitions continue to vary as to what exactly an entrepreneur is. The entrepreneur has variously been defined as a person who pursues opportunity regardless of resources currently controlled;2 brings resources, labor, materials, and other assets into combinations such that their value is greater than before;3 and innovates by developing and applying new technology.4

The importance of innovation to entrepreneurship was the critical insight of Joseph Schumpeter, who defined an entrepreneur as someone who “revolutionizes the pattern of production by exploiting an invention or, more generally, an untried technological possibility for producing a new commodity or producing an old one in a new way.”5 By linking the idea of entrepreneurship to that of innovation, Schumpeter emphasized the creative aspect of enterprise formation. He also recognized that innovation could take many forms, including product innovation, marketing innovation, process innovation, and organizational innovation. The driving force behind innovation is the entrepreneur and his impulses. “First of all, there is the dream and the will to found a private kingdom, usually, though not necessarily, a dynasty.… Then there is the will to conquer, the impulse to fight, to prove oneself superior to others, to succeed for the sake, not of the fruits of success, but of success itself.… Finally, there is the joy of creating, of getting things done, or simply exercising one’s energy and ingenuity.”6 By focusing on the social motivations of economic activity, Schumpeter attempted to move beyond the economist’s usual attraction to explanations based on rational choice and efficiency maximization.

As a behavioral phenomenon, entrepreneurship can quickly become a highly creative and personal process. The entrepreneur has an important role in shaping the new organization, which often reflects his or her priorities and visions. How, then, can we understand the process by which entrepreneurs gravitate to different kinds of undertakings and organizations? The answer is that entrepreneurs are attracted to endeavors that fit their personalities, skills, and expertise. Howard Stevenson has argued that there is a spectrum of entrepreneurial business behavior—one that runs the gamut from the pure promoter who is willing to do anything to achieve the desired result to the trustee who focuses on the effective use of resources currently on hand.7 While in the past the link between personality and entrepreneurial activity centered on different business fields (manufacturing, retail, professional services, etc.), we now think more in terms of entrepreneurship across all three societal sectors. Entrepreneurship is now not only part of the business sector but also a prominent component of the public sector, where policy entrepreneurs drive ideas from conception through legislation. Social entrepreneurship has been equated with the pursuit of important missions and purposes. It is the driving force behind the entry of a new generation of people attracted to doing good.

Entrepreneurship has emerged as a critical mover and shaper of nonprofit ideas and programs. Driving this process has been a generation of nonprofit entrepreneurs who have approached their work with open minds about nonprofit financing and mission definition. Instead of looking at the guidelines of government funders or at the demands of certain constituencies, this new group has started asking questions: What interests me? Where do I best fit? Because theories of entrepreneurship are essentially behavioral ones, there are attempts to develop detailed frameworks and typologies that help us organize the range of possible answers to these kinds of questions.

One of the earliest attempts to develop a theory of social entrepreneurship rests on a typology of personalities within the nonprofit world: Dennis Young’s models of entrepreneurs and nonprofit motivations.8 His models of entrepreneurs are best thought of as “pure types.” (In reality, many people will represent some combination of the various traits and motivations in Young’s pure types.) A first type, the artist, is attracted to nonprofits by the promise of finding a place where his or her own creative energies can be translated into organizational and programmatic reality, and the need to create, nurture, and watch organizations grow can be fulfilled. The professional is more discipline bound and will seek to implement the latest insights and ideas in the field. The believer is an entrepreneur who has a strong commitment to a cause and formulates his or her plans to advance a particular moral, political, or social cause. The searcher is out to prove him- or herself, to find a niche, and to escape his or her current employment in pursuit of recognition and a clearer sense of identity. The independent enters the sector to find autonomy instead of working under others, to be the boss who calls the shots, and to avoid shared decision making. The conserver is a loyalist who is animated by a desire to preserve an organization’s character and heritage. Finally, according to Young, the power seeker is drawn to nonprofit work by the possibility of having authority over other people, sometimes for the sake of simply having control over others, sometimes to reap financial rewards.

To build a theory around these pure types, Young goes on to describe a two-part “screening process,” the first of which filters the various types of entrepreneurs into different fields of nonprofit activity. How does this screening or matching process work? Entrepreneurs will gravitate to various parts of the sector depending on four factors: (1) the intrinsic nature of the services delivered; (2) the degree of professional control; (3) the level of industry concentration; and (4) the social priority of the field.

To understand how this fourfold screening process within the sector might operate, consider two different nonprofit organizations—one a homeless shelter and the other a major performing arts organization. Some individuals will gravitate to shelters because they want to work in a field where services are provided directly to clients, professional standards for service delivery are far from fixed, many small organizations populate the field, and the need for the given services is such that public support for the work is strong. On the other hand, other individuals will be attracted to creating an independent theater company because they like the idea of working in a context where the client is a bit removed from the daily work of the organization, standards of artistic excellence are determined by a small group of opinion makers, only a few organizations dominate the scene, and public support is not a major consideration, because work is directed toward pleasing a small, well-defined elite group. Obviously, the calling to create an effective and compassionate shelter is very different from that of running a professional theater; just as obviously, believers and searchers are more likely to apply their entrepreneurial skills to the delivery of needed social services, whereas artists and independents are better suited to the cultural world.

The goal of behavioral theories of entrepreneurship is to render these broad-brush generalizations more concrete and consistent by elaborating on both the motives of the entrepreneur and the characteristics of the enterprises in which these entrepreneurs pursue their work. Beyond a filtering by field, entrepreneurs will also be screened by the choice of sector they make. Entrepreneurial energies may find expression in public agencies, business firms, or nonprofits. This second part of the selection process is driven, according to Young, by three factors: (1) the desire to realize income; (2) the level of hierarchy and bureaucracy that is acceptable; and (3) orientation toward service. Thus, for example, another type defined by Young, controllers (entrepreneurs who want to maintain control over the enterprise), who seek financial gain, are more likely to gravitate to the business sector, while searchers are more likely to find their way to nonprofits. Because much variation exists across fields within each sector, and because conditions are constantly changing within fields, ironclad predictions cannot be made. A screening theory based on motives and behavior gives us a framework for thinking about the ways in which the matching process of opportunities with interests takes place and how skills and motives come into alignment.

If one accepts the notion that a behavioral theory of social entrepreneurship involves both a typology of motives and a matching or screening process that connects these motives to specific parts of the organizational landscape, the challenge then becomes one of clearly specifying both these critical elements. While Young’s early model moves in the right direction, more work is still needed to define the archetypes of nonprofit motivation and the organizational channels that direct these impulses. In particular, a more fully elaborated cross-sectoral theory of what draws particular types of people to particular types of entrepreneurial ventures is still needed, especially for the critical issue of sector selection. As mentioned earlier, Young’s model is rooted in the traditional three-sector paradigm, but now that boundaries have blurred between nonprofit and for-profit forms, a new theoretical lens is needed.

Dees’s work on sector selection provides a useful starting point for new theory building. Dees has argued that sector selection comes down to four critical considerations: (1) efficiency of structure and the ability to mobilize human and financial capital; (2) economic robustness and how the form will fare in the competitive environment; (3) political viability or the extent to which goodwill is needed; and (4) the values of key stakeholders. The problem with these four drivers is that they leave out the fundamental insight of Young and others that the personality and motivations of the entrepreneur will be critical to understanding the fateful choice of organizational form. Our model simplifies and integrates Young’s ideas with those of Dees, and produces a concise yet comprehensive predictive model.

Instead of looking at what pulls donors, staff, and volunteers into nonprofit and voluntary organizations, we begin to get a picture of what pushes these individuals toward doing good. Some may be attracted to socially oriented businesses (like Levi Strauss or Ben & Jerry’s), while others will be attracted to commercial nonprofits (like hospitals). Still others will seek out community groups that are dedicated to a particular social cause. It is clear that social entrepreneurship can and does occur in all these contexts and many others. Social entrepreneurs will scan the environment and select the causes and organizational forms that best fit their interests and needs. Understanding not just how they make this choice in practice but also how they should make this choice is the challenge of a compelling normative theory of sector selection.

Introduction to the Model

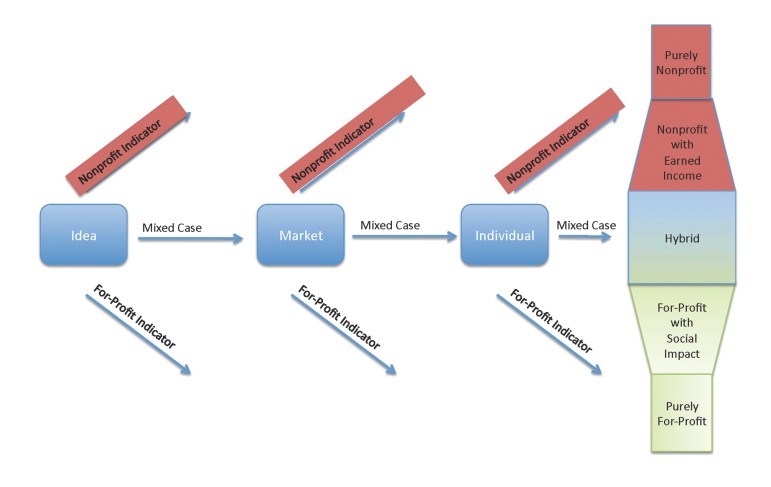

Our normative model for sector selection rests on three key elements that result in a recommendation to the social entrepreneur of one of five organizational types. As you will learn in greater detail shortly, these three elements turn out to be the idea or the nature of the value proposition; the market or the competitive environment; and the personal traits or disposition of the entrepreneur. Each of the three elements in the model rests on a key question that has three possible answers—one that leads to a preference for the for-profit model, another that leads to a preference for the nonprofit model, and a third, mixed case. In the mixed case, the entrepreneur may not conclusively agree with an answer that indicates either the for-profit or the nonprofit model and instead may respond with “neither” or “both.” The three key elements of the model are independent of one another. It is the cumulative result of deliberating over all three elements that yields the final recommendation as to where the organization should lie on the social enterprise spectrum. For the three elements with three possible answers to each underlying question, a total of twenty-nine unique outcomes are possible. However, these outcomes can then be organized into three categories: pure types, dominant types, and inconclusive results. There are two pure types—pure for-profit and pure nonprofit—and two dominant types—a dominant nonprofit with an earned-income component and a dominant for-profit with a social mission. Cumulative results that do not fall into one of these categories are labeled “inconclusive.” Each of these types will be discussed in further detail.

Identifying the Determining Characteristics

In the total possible universe of determining characteristics that could be used to construct a sector selection model, a surprising number of factors are no longer relevant because of the blurring distinction between nonprofit and for-profit organizations. For example, at one point, public trust was reserved predominantly for nonprofit organizations, and as a result, most public-serving institutions, such as schools and hospitals, were nonprofit. Now, new forms of public trust in for-profits, earned by a respect for efficiency and emphasis on results, mean that for-profit models for public-serving institutions are not only possible but also increasingly popular and effective. Likewise, profit generation was once mostly taboo for nonprofit organizations, which in the past may have minimized and compartmentalized revenue-generating activities. Now, earned income is a hallmark of financial diversification, and nonprofits nationwide are building profitable businesses within their nonprofit organizations.

Similarly, several factors that may be influential in leading an entrepreneur toward one organizational type over another are not in themselves unilaterally predictive. Though they may lean toward one organizational type, those factors are more accurately identified as suggestive rather than predictive, because they contain several exceptions in which they could lean toward the opposite organizational type. Because of the complexity of the considerations related to sector selection, we argue that it should come relatively late in the enterprise planning process, after many practical and operational details have been worked out.

Three Key Assessments

As mentioned earlier, the model we propose identifies three key assessments that we consider comprehensive and conclusive: the social value proposition; the competitive environment; and traits of the entrepreneur. Though at first this may appear to be a reductionist approach, each assessment contains specific and detailed questions that can be effectively answered only by an entrepreneur with a deep understanding of his or her idea, a grasp of the market in which he or she will operate, and a sense of his or her priorities and motives.

Social Value Proposition

A first step in sorting the options across the social enterprise spectrum relates to the idea of a social value proposition. In trying to assess the best organizational form through which to pursue value creation, we argue that a critical judgment needs to be made about the kind of equity that will be built. Specifically, this assessment asks: “On what type of equity model is this idea based?” It presents three possible answers: social equity, private equity, or a mixed case. Ideas based on a social equity model are publicly oriented. They usually depend on a public perception of impartiality or substantial contributions of volunteer support for their realization, and often what is created is a public good, such as knowledge or clean air. Furthermore, organizations based on a social equity model are usually more dependent on trust or the amount of goodwill and commitment necessary to make the product or service attractive to clients or customers. Trust is essential when dealing with vulnerable populations or when the product is controversial and untested.

In contrast, ideas based on a private equity model are, as the name suggests, privately oriented. Value is usually concentrated, more easily quantifiable, and convertible into monetary terms. In the private equity model, value accrues to one or more private entities and usually depends on a clearly articulated and defensible asset, such as an intellectual property or patent.

Within this key assessment, ideas that are based on a social equity model are best served by a nonprofit organization, thus yielding a nonprofit result. Likewise, ideas based on a private equity model are best served by a for-profit organization, thus yielding a for-profit result. If the social entrepreneur cannot definitively affirm either equity model, then this assessment is ruled a mixed case. To effectively answer the question of which equity model is in play, the social entrepreneur must first have a clearly articulated concept. Is it a product, service, or program? How will it yield results? What differentiates it from others in the space? The social entrepreneur must understand which key nonfinancial components are critical for success.

Competitive Environment

The second driver of sector selection relates to the nature of the competitive environment. Specifically, it asks: “What are the human and financial resources needed?” The main assessment relates to the presence or absence of paying customers. Fairly assessing who, if anyone, will pay for the product or service being proposed is a critical step toward appropriate sector selection. In cases where a prospective consumer will not be able to afford the service or product being developed, a focus on philanthropic inputs may drive selection of the nonprofit model. In instances where a large group of customers are ready and able to pay for a product or service, the entrepreneur may well be advised to form a for-profit firm. And, of course, there will be mixed cases where some customers will be ready and able to pay while others will not.

This category of assessment presents three possible answers: a direct-payer model, a third-party-payer model, or a mixed case. In the direct-payer model, customers are available who are not only willing but also able to pay for the product or service. As a result, there is a direct flow of funds from the customers to the organization. In the third-party-payer model, there either are no customers or the customers are not able to pay for the program or service. In the latter case, a third-party payer is required to subsidize or fund the product or service provided by the organization. The third-party-payer model is also one that often relies on large numbers of unpaid partners or volunteers for the viability of its financial model.

Direct-payer models are best served by a for-profit organization, and if the market context relies on a direct-payer model, then the answer for this assessment is “for-profit.” In contrast, third-party-payer models are best served by a nonprofit organization, and would yield a nonprofit result. If the model is not clearly direct payer or third-party payer, then the result would be the mixed case. To effectively answer the questions related to this assessment, the social entrepreneur must understand the type of pricing model he or she will deploy, which in turn is usually dependent on a keen understanding of the competitive landscape, including the types of clients and/or customers, their ability to pay, and what other organizations are charging for similar products, services, or programs.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Several suggestive factors related to the market context should be noted for this discussion. Taken alone, these factors are not predictive and therefore are not incorporated in the sector selection model; however, they can be used in a secondary process for refinement of position along the social enterprise spectrum. For example, one set of suggestive factors relates to the amount and type of start-up capital required. If the entrepreneur is pursuing an idea that requires large volumes of highly flexible capital, he or she is most likely best served by a for-profit organization that benefits from a greater variety of and accessibility to capital than nonprofit organizations.

Traits of the Entrepreneur

A final driver comes down to the personal traits of the social entrepreneur. Choosing among nonprofit, hybrid, and for-profit forms depends to a certain extent on the personality of the entrepreneur, who will be doing the bulk of the work—at least at the outset—of translating vision to reality. All social entrepreneurs have deep-seated beliefs and behaviors that affect their success in the context of different organizational models. A key trait of the entrepreneur is his or her inclination toward acquisition versus distribution. This assessment asks whether the entrepreneur prefers a distributive or an acquisitive approach to value creation. To successfully evaluate this category, the social entrepreneur must be clear about how he or she believes value creation through the organization can be maximized. A fundamental personal orientation toward self is different from one that is other-oriented and committed to redistribution.

In the distributive approach, value, power, and wealth are shared among a large number of stakeholders. In the acquisitive approach, value, power, and wealth are centralized among a smaller number of private individuals. The preference for one approach over the other has substantial consequences for ownership, decision making, and personal ambition. For example, in the distributive model, ownership is absent or diffuse—and, as a result, decision making is, too. In the distributive model, the opportunities for the social entrepreneur to accumulate personal wealth are limited. Under an acquisitive model, ownership and decision-making authority are retained along with the possibility of personal wealth accumulation.

Entrepreneurs who are motivated by the distributive model will be best served by a nonprofit organization. Those who are motivated by an acquisitive model will be best served by a for-profit organization. And, those for whom neither choice is a good fit will fall into the mixed case.

Taken together, these three assessments related to the nature of the social value proposition, the conditions in the competitive environment, and the traits of the entrepreneur constitute the foundation of our normative theory of sector selection.

Applying the Model

Because each assessment directs the entrepreneur toward one of the three outcomes, the cumulative result of all three assessments yields the final result. The cumulative answers to the set of three assessments will indicate that the entrepreneur should select one of five possible organizational types. As described earlier, there are two pure types (pure nonprofit and pure for-profit), two dominant types (nonprofit with earned income and for-profit with social mission), and two inconclusive results (the pure hybrid form and a generic inconclusive result). A visual representation of the three assessments and the social enterprise spectrum is presented in the graphic below.

![]()

The methodology used to translate the answers to each assessment into a category recommendation for an organization can be easily understood by ascribing a simple scoring system to the answers. For example, answers pointing to the for-profit result can be signaled with a “1,” those pointing to the nonprofit result, a “–1,” and those pointing to the mixed case, a “0.” Using this scoring system, we can catalog the possible outcomes in sets of three numbers. For example, if the entrepreneur responded to each question with the for-profit answer, then the solution set would be (1, 1, 1). Likewise, if the entrepreneur answered each question with the nonprofit answer, then the solution set would be (–1, –1, –1). Finally, three mixed-case results would yield (0, 0, 0). These three examples illustrate the pure types.

The methodology used to translate the answers to each assessment into a category recommendation for an organization can be easily understood by ascribing a simple scoring system to the answers. For example, answers pointing to the for-profit result can be signaled with a “1,” those pointing to the nonprofit result, a “–1,” and those pointing to the mixed case, a “0.” Using this scoring system, we can catalog the possible outcomes in sets of three numbers. For example, if the entrepreneur responded to each question with the for-profit answer, then the solution set would be (1, 1, 1). Likewise, if the entrepreneur answered each question with the nonprofit answer, then the solution set would be (–1, –1, –1). Finally, three mixed-case results would yield (0, 0, 0). These three examples illustrate the pure types.

The dominant cases are those in which two of the three answers are for one type, such as (1, 1, 0), (1, 1, –1), (–1, 0, –1), and (–1, 1, –1). There are eighteen dominant cases. The nonprofit-dominant cases are interpreted to yield a “nonprofit with earned income” enterprise type, and the for-profit dominant cases are interpreted as a “business with social mission” enterprise type. The dominant mixed cases are interpreted as hybrids.

The third set of cases represents inconclusive results. The (0, 0, 0) result, in which the entrepreneur’s answers are mixed for each assessment, points toward a hybrid model; however, due to the answers’ inherent ambiguity (they could be interpreted as neither or both), the pure mixed case does not clearly point to an organizational type. Instead, the (0, 0, 0) result is inconclusive. Similarly, in six additional inconclusive cases, none of the three factors is the same—(1, 0, –1), (0, –1, 1), and so forth. In these cases, the resulting organization would likely be a hybrid one that is not functioning optimally from the standpoint of either sector.

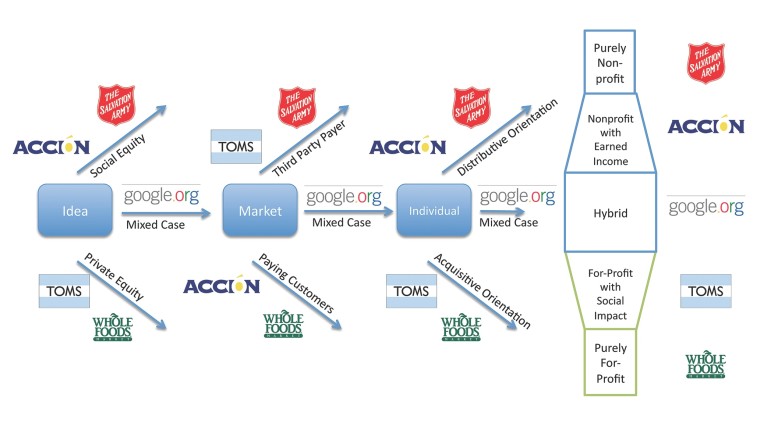

To better understand the implementation of the normative theory, we present case studies for the five main organizational types—pure nonprofit, pure for-profit, dominant nonprofit, dominant for-profit, and hybrid/inconclusive. These case studies illustrate how the answers to each assessment can predict a preferred organizational type.

Pure Types

Pure Nonprofit: Salvation Army

The Salvation Army began in 1865, when its founder, a London minister named William Booth, decided to step out from his pulpit and work in the streets among the poor. Booth’s original intention was to convert the poor to Christianity and encourage them to attend local churches; however, he soon discovered that few of the churches of the day were eager to have the poor share pews with their regular congregants. So Booth founded a church aimed at meeting the needs of the London poor. The Salvation Army now operates churches or citadels in one hundred and twenty-six countries around the world, and links traditional religious services to vast outreach efforts aimed at helping those in need. It has a revenue of $4.3 billion, and works with some thirty million people. Even though the Salvation Army’s worldwide scope is immense, it continues to grow strategically, focusing on a mix of programmatic activities that varies from location to location, depending on local needs. The ability of the Salvation Army to draw from its diverse portfolio of tested programs and initiatives allows it to adapt to the shifting roles it is called to play in locations around the world. Among its distinctive features are its ability to motivate and inspire its workers, its reliance on a hierarchical governance model grounded in ranks, and its reliance on over three million volunteers.

The Salvation Army looks and behaves like a traditional nonprofit because its fundamental mission is the creation of social benefits, particularly for the economically disadvantaged. While it is financially successful, it measures its impact in terms of the amount of good it does in the world. When it comes to the environment in which it operates, the Salvation Army depends heavily on third-party payers, be they government agencies providing contracts for the provision of human services or individuals who drop coins in the holiday kettles. Finally, if one looks back at the motives of the founder, the driving forces were Booth’s desire to help others and to deliver on a vision of social redistribution that focuses on meeting the needs of the poor.

Pure For-Profit: Whole Foods

Formed in 1980 with one small store in Austin, Texas, Whole Foods is now one of the world leaders in natural and organic foods, operating more than 410 stores in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States.9 The main business model centers on providing high-quality natural and organic foods, maintaining high quality standards, and remaining true to the idea of sustainable agriculture. Whole Foods’ mission comes down to three main elements, which became the company’s motto: “Whole Foods, Whole People, Whole Planet.” As described on the website, by “whole foods” the company means engaging in a continuous search for “the highest quality, least processed, most flavorful and natural foods possible because we believe that food in its purest state—unadulterated by artificial additives, sweeteners, colorings and preservatives—is the best tasting and most nutritious food there is.” The second element relates to the quality of the people who are employed by the company: “Our people are our company. They are passionate about healthy food and a healthy planet. They take full advantage of our decentralized, self-directed team culture and create a respectful workplace where people are treated fairly and are highly motivated to succeed.” The final element relates to sustainability and the environment: “We are committed to helping take care of the world around us, and our active support of organic farming and sustainable agriculture helps protect our planet.”

While commendable in its humanistic and environmental goals and thinking, Whole Foods is a for-profit through and through. It competes aggressively with other grocery chains and it generates profits for its shareholders. It also meets all three definitive characteristics of the for-profit type: first, it focuses on building private financial equity for its shareholders; second, the company depends on paying customers to grow and thrive; and third, cofounder and CEO John Mackey’s vision was more acquisitive than redistributive—and, lately, he has come into the public eye as a prominent and articulate defender of the libertarian perspective.

Dominant Types

Dominant Nonprofit: ACCION

As one of the global leaders in the microlending movement, ACCION International gives economically disadvantaged people “the financial tools they need to work their way out of poverty.”10 By providing microloans, business training, and other financial services to economically disadvantaged men and women who start their own businesses, ACCION strives to bring up to date the goal embodied by the proverb, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” ACCION defines itself as pursuing “a vision in which all people have access to a range of high-quality financial services that enhance their economic potential and the quality of their lives.” To do so, it engages in a range of programmatic activities and has reached close to four million people to date. ACCION’s work includes partnerships with twenty-nine microfinance institutions (MFIs), NGOs, and commercial banks across North America, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. ACCION assists its partners in developing and delivering financial services for the disadvantaged. Technical assistance and management services are offered to help these organizations “launch, transform and expand their microfinance programs.” ACCION also offers “training and education on the microfinance process, to build staff capacity and better position MFIs to achieve their social and financial goals.” Because a microfinance program “requires advances in risk management, service delivery to remote areas and technology,” ACCION “pilots new microfinance products and processes in ‘Innovation Labs.’” And, ACCION provides “equity financing and loan guarantees to institutions. These funds enable institutions to invest in resources such as better core-banking systems and more branches to improve services and increase reach.”

While ACCION is a nonprofit organization, it has some of the elements of a for-profit entity. It is focused not on giving money away but rather on supporting programs that lend funds that are repaid with interest. Its metrics are largely social, yet it does measure repayment rates and track returns. Its payers are third-party donors, yet it recirculates funds that its clients pay back into the organization. The main entrepreneurial drive is clearly redistributive. This is likely the factor that tilted ACCION to ultimately select the nonprofit model.

Dominant For-Profit: TOMS Shoes

In 2006, American traveler Blake Mycoskie befriended children in Argentina and saw that they had no shoes to protect their feet. Wanting to help, he created TOMS Shoes—a company that would match every pair of shoes purchased with a pair of new shoes given to a child in need, using a model they call “One for One.” Mycoskie returned to Argentina with a group of family, friends, and staff later that year with ten thousand pairs of shoes, made possible by TOMS customers. His business has thrived ever since. As consumers have embraced TOMS, Mycoskie has been able to convert sales into philanthropic donations via shoe drops organized by the company in Argentina, Ethiopia, and South Africa. To date, TOMS has distributed over thirty-five million pairs of shoes to needy children around the globe. The shoes that Mycoskie sells to consumers are priced from $45 to over $70, though they cost only a fraction of that to make. Still, the shoes make the buyer feel good about helping children around the world, and also represent a sign to others that the wearer has a social conscience.

The equity created by TOMS is both financial and social in nature. The company sells millions of dollars worth of shoes and generates a substantial margin for its owners. At the same time, its promise to give away shoes creates social equity for the poor by providing them with a way to avoid disease and discomfort, thus helping them get to school and live fuller lives. The payer is third party when it comes to the shoes that are distributed, but at the same time there is a direct customer base of affluent young people who find the shoes and message appealing and are willing to pay for that. When it comes to Mycoskie’s own entrepreneurial motives, they, too, are mixed: he has both a strong commitment to redistribution and an acquisitive desire to build a strong, valuable company.

Hybrid/Inconclusive

Google.org

Google.org was formed in 2004 by Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin to pursue Google Inc.’s philanthropic goals. The original mandate was very broad—to address climate change, poverty, and emerging disease—and unlike the Google Foundation, which was formed as a traditional grantmaking entity, Google.org was formed as part of Google Inc., with the intention of making both nonprofit grants and for-profit investments. The sole funding source of Google.org is equity and profits from Google Inc., which pledged 1 percent to Google.org in addition to in-kind contributions of employee time and technology resources. To date, Google.org has deployed more than $100 million in capital to more than fifty projects around the globe.

Over the past six years, Google.org has struggled substantially with its mission and activities as it has sought to better leverage its business assets as well as to more clearly articulate its unique philanthropic purpose. For example, on the Google.org website, a program update reads: “When we reviewed our progress in early 2009, it became clear that while our partners were doing excellent work with our grant funding, we could do more to effectively use Google’s engineering talent by focusing on the technical contributions we could make. We shifted our focus to engage in engineering projects. We continue to manage an existing portfolio of grants and investments and the Google Foundation.” In these struggles, we can begin to see the consequences of an indeterminate organizational type. Though located under the umbrella of the for-profit parent company, the investments made by Google.org do not yield private return and are seen as having primarily social goals. Thus, the answer to the type of equity created is a mixed case. Furthermore, questions related to the market and presence of paying customers and to the dual approach of grantmaking and investments also yield a mixed result. Finally, the motivations of the social entrepreneurs seem to be torn between distributive and acquisitive, leading to a third mixed-case response.

The pathways to organizational form selection for each of the preceding five cases can be depicted as a series of choices across the three critical assessments related to the idea, market, and individual/entrepreneur (as the graphic below demonstrates).

![]()

While these cases represent an application of our model to mature organizations, we believe that new entrepreneurs could use this framework to help answer the question of initial sector selection when a long operational history has not already been defined.

While these cases represent an application of our model to mature organizations, we believe that new entrepreneurs could use this framework to help answer the question of initial sector selection when a long operational history has not already been defined.

…

As the organizational landscape becomes increasingly variegated and filled with organizations that defy easy classification, a theory of sector selection becomes at once more critical and complicated. The model we present has the virtue of bringing together in a succinct and relevant way ideas that have been circulating in isolation for some time. By focusing on the nature of the idea at hand, the competitive landscape surrounding this idea, and the personal disposition and outlook of the entrepreneur, our model melds conceptual, environmental, and psychological considerations. At the same time, by anchoring those aspects in a diagnostic framework, it presents a preliminary tool that can be used by early-stage social entrepreneurs to make an informed decision about organizational type, evolving beyond ambiguous preferences to a theory rooted in critical distinctions and clear advantages of one choice over another.

Notes

- See J. Gregory Dees, Social Enterprise Spectrum: Philanthropy to Commerce, Case #9-396-343 (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996) and J. Gregory Dees, “Enterprising Nonprofits,” in Harvard Business Review on Nonprofits (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1999), 135–166.

- Howard H. Stevenson, Michael J. Roberts, and H. Irving Grousbeck, New Business Ventures and the Entrepreneur (Illinois: Richard D. Irwin Publishing, 1994).

- Karl H. Vesper, New Venture Strategies (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980).

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, Can Capitalism Survive? (New York: Harper & Row, 1952).

- Ibid., 72.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle, trans. Redvers Opie (New York: Harper & Row, 1947), 93.

- Stevenson, Roberts, and Grousbeck, New Business Ventures and the Entrepreneur.

- Dennis R. Young, “Entrepreneurship and the Behavior of Nonprofit Organizations: Elements of a Theory,” in The Economics of Nonprofit Institutions: Studies in Structure and Policy, ed. Susan Rose-Ackerman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 161–184.

- Background information on Whole Foods was taken from the company’s websites.

- Background information on ACCION was taken from the organization’s website and from NGO Portal.

Peter Frumkin is the Mindy and Andrew Heyer Chair in Social Policy, director of the Master’s in Nonprofit Leadership Program, and faculty director of the Center for Social Impact Strategy at the University of Pennsylvania. He is author of On Being Nonprofit: A Conceptual and Policy Primer (Harvard University Press, 2005) and Strategic Giving: The Art and Science of Philanthropy (University of Chicago Press, 2006), among other titles. Suzi Sosa is cofounder and CEO of Verb, an Austin, Texas–based social enterprise that leverages the power of technology and networks to accelerate thousands of early-stage social entrepreneurs through competitions and challenges.