July 20, 2018; Washington Post, Forbes, and Inside Higher Ed

As NPQ covered a month ago, a proposal by the nonprofit College Board to lop off 9,000 years from the world history curriculum was not well received by many history teachers and their students. At the time, Trevor Packer, senior vice president of Advanced Placement and instruction at the College Board, hinted that some kind of adjustment was in the work.

“Constructive feedback,” said Packer, “has suggested a path forward that will enable us to achieve several priorities that I believe we share and can agree on.”

What was that constructive feedback? Apparently, it was to only lop off 8,750 years. Problem solved.

As Valerie Strauss writes in the Washington Post, “Responding to an outcry over proposed changes, the College Board has agreed to restore 250 years to its AP World History course to ensure that students learn how civilizations outside Europe influenced the modern era. The course will start at the year 1200 rather than the previously announced shift to 1450.”

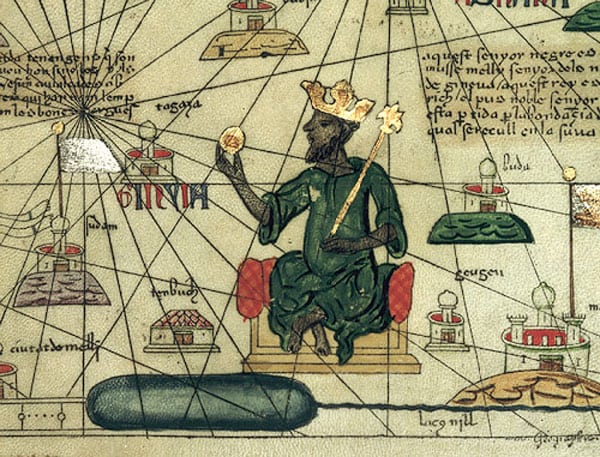

This change is an improvement over 1450, in that more non-Western history is likely to be included. A course beginning in 1200 might cover the Inca and the Aztecs in the Americas—hopefully, with an eye to understanding their rise before the Spanish conquistadores arrived—Mansa Musa and the Mali Empire in Africa, and the Mongol Empire in Asia.

Colleen Flaherty, writing for Inside Higher Ed, adds that according to the College Board, “Essential content for the 1200-1450 period includes global trade networks; state building in the Americas and Africa; how religion shaped Africa, Asia and Europe; and the intellectual, scientific and technological innovations and transfers across states and empires.” Some historians, such as Mary Beth Norton, president of the American Historical Association, have expressed relief that a more inclusive history is being preserved.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Still, a few things in human history did occur before 1200. Strauss mentions “the Neolithic/Agricultural Revolution; the creation of the first civilizations; the migration of humans across Earth; and the development of classical empires such as Rome, Greece and China.” One might add that most of the world’s major religions were founded well before 1200. And of course, this also leaves out a range of cultures and civilizations far too lengthy to name.

Writing in Forbes, Virginia Tech medievalist Matthew Gabriele notes that his colleague Monica Green, a medievalist at Arizona State, “said that the choice of the year 1200 CE seemed a bit odd.” According to Green, where you begin a story “depends on what kind of story you want to tell. If the AP wants to tell the story of the history of nation-states, then maybe ca. 1200 is the ‘correct’ place for them to do so…[But] I want to tell stories about how humans have dispersed and innovated and reconnected repeatedly. I trained as a Europeanist and a Medievalist. For many historical questions…you need a viewpoint with a larger perspective.”

The sad part of all of this is that it is precisely this question of what stories should be told in world history that the College Board has studiously avoided.

“Currently,” writes Flaherty, “the single AP World History exam covers about 10,000 years. While some teachers like the scope of the exam, others say that it is simply too sweeping and that real learning suffers as a result.”

But this is hogwash. Certainly, as NPQ noted, “learning 10,000 years of history does require more than a year.” But truth be told, the same holds for 550 years (or, now, 800 years). Still, it is possible to create a course that can be manageably taught in a year for advanced placement high school students that includes the classical period. The problem is not one of having to cover too many years, but rather a failure to settle on key themes that make for a coherent curriculum.

In the end, however, the College Board has found it easier to lop off years rather than do the admittedly complicated work to build a consensus in the field as to what are the essential themes of world history high school students should learn. This “post-Renaissance plus selected non-Western history” approach may appease some, but, as Green notes, it leaves out a lot of “world history that everyone should know. We are all inheritors of the global human experience.”—Steve Dubb