January 15, 2019; New York Times

Last June, NPQ reported that Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey named eight Sackler family members as defendants in a complaint that accused Purdue Pharma of spinning a “‘web of illegal deceit’ to boost profits.” Now, a 312-page document in state court provides new details regarding how that web was constructed.

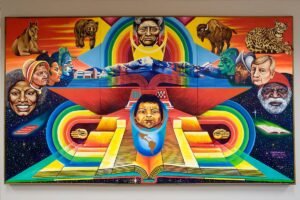

The descendants of Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, the nation’s 19th-wealthiest family, are, as NPQ has noted, major names in arts philanthropy. Last year, photographer Nan Goldin, herself an opioid addiction survivor, led a museum-based protest action to call attention to the connection and call on the family to make amends. In an article published in the Guardian, NPQ staff also pointed out that the Sacklers have been “generous patrons of medical research at the nation’s leading universities, including Columbia, Cornell, Tufts and Yale.”

As the death toll from opioids in the United States has grown to approach 218,000 (as of year-end 2017), hundreds of states, cities, and tribal governments have filed suit. The Massachusetts suit, however, is unique in making the Sacklers themselves defendants.

Now, as Barry Meier writes in the New York Times, Massachusetts is using previously undisclosed documents to argue that the Sacklers were not just beneficiaries of OxyContin profits, but also architects of many of the deceptive practices of Purdue Pharma. As Meier puts it, the state’s claim is that, “Members of the Sackler family, which owns the company that makes OxyContin, directed years of efforts to mislead doctors and patients about the dangers of the powerful opioid painkiller.”

For example, paragraph 8 of the state’s complaint contends that “Defendants Richard Sackler, Beverly Sackler, David Sackler, Ilene Sackler Lefcourt, Jonathan Sackler, Kathe Sackler, Mortimer Sackler, and Theresa Sackler controlled Purdue’s misconduct. Each of them took a seat on the Board of Directors of Purdue Pharma Inc. Together, they always held the controlling majority of the Board, which gave them full power over both Purdue Pharma Inc. and Purdue Pharma LP. They directed deceptive sales and marketing practices deep within Purdue, sending hundreds of orders to executives and line employees. From the money that Purdue collected selling opioids, they paid themselves and their family billions of dollars.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In particular, emails cited in the complaint show members of the Sackler family engaged deeply in company operations. For example, Richard Sackler, Purdue Pharma president at the time, in 2001 wrote an email that advocated that the company push blame onto the people who had become addicted, writing, “We have to hammer on abusers in every way possible. They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”

Other specific allegations in the complaint include:

- “In 1997, Richard Sackler, Kathe Sackler, and other Purdue executives determined—and recorded in secret internal correspondence—that doctors had the crucial misconception that OxyContin was weaker than morphine, which led them to prescribe OxyContin much more often, even as a substitute for Tylenol” and advocated taking advantage of that misperception to increase drug sales.

- In February 2001, when a federal prosecutor reported 59 deaths from OxyContin in a single state, Richard Sackler, who the complaint alleges knew the number was an underestimate, wrote to Purdue executives that, “This is not too bad. It could have been far worse.”

- From 2007 to 2018, the Sacklers maintained tight control, directing “the company to hire hundreds more sales reps to visit doctors thousands more times. They insisted that sales reps repeatedly visit the most prolific prescribers. They directed reps to encourage doctors to prescribe more of the highest doses of opioids. They studied unlawful tactics to keep patients on opioids longer and then ordered staff to use them…They sometimes demanded more detail than anyone else in the entire company, so staff had to create special reports just for them.”

Much of the report details, blow by blow, instances in which different family members followed up on sales numbers and advised staff regarding marketing tactics. One example appears in paragraph 392 of the complaint:

In January 2013, in what was becoming a yearly ritual, Richard Sackler questioned staff about the drop in opioid prescriptions caused by Purdue sales reps taking time off for the holidays. Richard wasn’t satisfied: “Really don’t understand why this happens. What about refills last week? Was our share up or down?” Staff assured Richard that doctors were “sensitive” to sales rep visits and, as soon as the reps got back into action, they would “boost” opioid prescriptions again.

The impact of the Massachusetts case remains to be seen, but the email correspondence uncovered does make it much harder for the Sackler owners at Purdue Pharma to maintain a position of innocence. “For years,” notes Meier, “Purdue Pharma has sought to depict the Sackler family as removed from the day-to-day operations of the company. The Sacklers, whose name adorns museums and medical schools around the world, are one of the richest families in the United States, with much of their wealth derived from sales of OxyContin. Disclosure of the documents is likely to renew calls for institutions to decline their philanthropic gifts.”—Steve Dubb