August 28, 2018; Dollars and Sense and Next City

Los Angeles, like most US urban centers, is home to great wealth inequality, marked by a growing number of low-wage and gig economy jobs that undermine economic security, as well as rising housing costs propelled by gentrification. To counter these trends, entrepreneurs like Kateri Gutierrez and business partner Jonathon Robles are looking to worker cooperatives.

Gutierrez, who studied business at the University of California, Berkeley, and worked for Disneyland, left corporate life to return to her hometown of Lynwood in Southeast Los Angeles County. It is a working-class area that is marred by pollution from old railroad yards and manufacturing plants, but with vibrant immigrant communities.

Gutierrez saw an opportunity to spur economic change in her community through community-minded business development “in which workers shared management and ownership”—i.e., through starting worker cooperatives. With Robles, she started Collective Avenue Coffee, a pop-up coffee shop that has spurred a mini-movement of cooperatives in the area.

Collective Avenue Coffee is moving from pop-up to brick and mortar business as part of COOP LA, a 10-person collective venture of four co-located cooperative businesses. Along with the coffee shop, COOP LA includes De La Luna Catering, Salazar Landscaping, and Semillas Wellness. According to Next City, COOP LA is the first commercial space in California comprised entirely of worker cooperatives.

“We’re going to revamp small business development, not from outsiders but by strengthening existing communities,” Gutierrez says. “We’re not keeping the community separate…we’re including them as part of the process.”

Los Angeles lags behind other major cities in cooperative development, according to a survey from the Democracy at Work Institute (DAWI), but an ecosystem to support cooperative development is emerging in the Southern California region. Partially to highlight this growth, the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives and DAWI will be holding their biennial national conference in Los Angeles next month.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In an article for Dollars and Sense, Antioch University professor Jane Paul describes the emerging worker-ownership network as a “polycentric system: a vibrant support network of cooperative developers, supports in the labor movement, worker- and community-based organizations, time banks, and legal and financial advisors.” Paul explains that the Los Angeles network “uses connections to peers in the social justice and economic development to create a space where people can grow and learn from one another. It is grounded in personal relationships, relies on volunteers and is anchored by established nonprofits.”

Among the key players in this eco-system is the LA Co-op Lab, a collective that provides training and support to build capacity for worker ownership in the region. The collective identifies worker-ownership as “one way to push back against inequality, gentrification, and the gig economy by helping people who are often excluded from good jobs to collectively create their own and meet community needs.” Other ecosystem partners include the labor movement and immigrant worker centers, both of which see cooperatives as an opportunity to address poverty, strengthen workers voices, and provide people with better job opportunities.

It takes a village to spur cooperative growth. The number of worker cooperatives—about 360—has grown slowly over the years. But there are signs of change. New York City saw a recent surge in new cooperatives as a result of a $2 million public investment. In 2017 alone, 36 new cooperatives were launched.

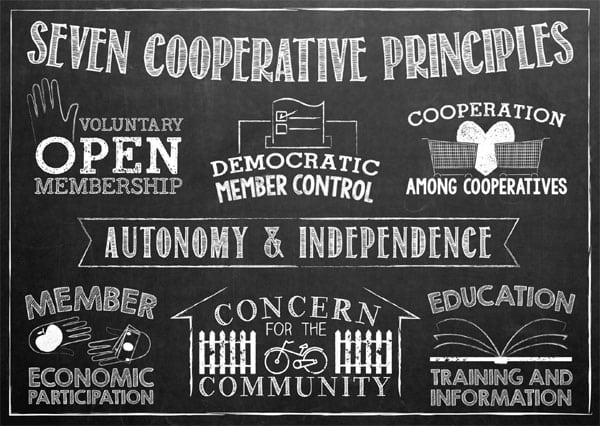

Worker-owned cooperatives provide the opportunity for workers not only to share in business profits, but to share in decision-making, to feel that they are contributing to their business and to their local economy. It’s empowering—very unlike being a cog in the wheel of a megacorporation.

Erik Rodas, the chef at De La Luna Catering, one of the COOP LA businesses, told Next City that he wanted to start a business “that would give opportunity to other people.”

COOP LA, he says, is “an active way to resist gentrification.” He notes, “there are a lot of anti-gentrification movements, but…they don’t provide any alternatives. We just see this as an opportunity to hold space.”— Karen Kahn