This article was first published by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and Mother Jones, with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, and is reprinted with permission.

Renee Taylor was busy when I spoke with her. She was making 500 meals, following the day’s menu—“tamales, tacos, rice, pico”—accompanied by the background clamor of clattering metal serving trays.

Following her release in 2013 after 25 years in various Chicago-area prisons, the 52-year-old Taylor has been prepping and delivering meals for the food service company ChiFresh Kitchen. This isn’t any old restaurant gig: Taylor owns a piece of her workplace. ChiFresh belongs to its five worker-owners, all of whom have also done time.

At worker cooperatives, workers both own and run the business. Sometimes they must buy in to become owners, and they may also have representation on a board of directors. Worker-owners tend to benefit far more directly from their co-op’s economic success, as the proceeds and the control stay with them. While co-ops make up a small portion of US small businesses, the pandemic and its aftermath have helped popularize the model. According to Mo Manklang, policy director of the nonprofit US Federation of Worker Cooperatives, there are now 465 verified worker-owned coops in the country, up 36 percent since 2013, and about 450 more are in their start-up phase.

Given today’s epic income inequality and tremendous corporate consolidation and union-busting, with the work that is actually available increasingly unstable and episodic, it’s no wonder that the people are drawn to a model that gives them back some power. The interest in co-ops marks a return to what Emily Kawano, the co-director of the co-op development organization Wellspring Cooperative Corporation, calls making a “livelihood” rather than just earning a paycheck.

Taylor, who had previously bounced between various retail jobs, was nervous at first about becoming a worker-owner, but she quickly warmed up to an unusual opportunity that included free classes in business fundamentals like bookkeeping that ChiFresh sponsors. “I really want to learn everything about the business,” she says. “I want to make it grow.”

In May 2021, three New York City drivers rolled out The Drivers Cooperative, a ride-hailing company and app owned and operated by cab drivers fed up with what they see as Uber’s exploitation of their work. They say they are now the largest worker cooperative in the country, with 3,500 members. The Drivers Cooperative co-founder Erik Forman, an organizer and a teacher with a taxi license, said he was inspired to create the co-op when frustrated drivers “kept coming to me to ask why we don’t start our own app.” At the beginning of their efforts, the driver-owners did emergency food delivery for the city during the pandemic, and also drove their first customers to early voting at the behest of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“Working class desire is for more control and even to own the place you work,” says Forman. While Uber and Lyft can take 25 percent off each of the drivers’ rides, the Drivers Cooperative plans to take only a commission of 15 percent while also giving the drivers any additional profits as dividends. As he was organizing the co-op, Forman ran online classes and got drivers to talk about their experiences on Zoom with the hope of building relationships among the drivers, leading to “consciousness raising,” as he puts it. New York City’s for-hire drivers are 91 percent immigrant and often also BIPOC. The co-op, Forman says, can be a model for “rethinking ownership as a way of rethinking racial justice.”

The new interest in worker co-ops can also be read as a reaction to the experience of our federal and local governments letting people down during the COVID-era. According to the Harvard University-based the Economic Tracker, there were 37.5 percent fewer small businesses open in June 2021 as there were in January 2020, before the pandemic. Partly as a result, millions of people have been laid off. “During the downturn, people turned to worker cooperatives,” says Manklang. “It’s typical of what people do when their government is unable to meet the moment.”

Worker co-ops expanded in the United States in another such moment, the 1880s, many of them founded by Black people after the Civil War. “When we were freed after slavery, and went to work, we got the worst jobs and the worst pay and the least disposable income,” says Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, author of Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. “Cooperatives were the way to get around” the exclusion from traditional businesses and even banks. At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, freed Blacks started mutual aid societies. They pooled members’ dues and monthly fees to pay for burials, and then additional stipends for widows and orphans, and shared money and work to buy and run farms.

The New Deal era also encouraged this cooperative work ethos, with the well-named Self-Help Cooperative Movement, which started in 1932 when unemployed people in the Compton neighborhood of Los Angeles contacted farmers outside of the city to set up a barter system: labor for food. (The co-ops back then made more than just food—the worker-owned Cooperative Industries of Washington, DC, for instance, manufactured barrels.) And these cooperatives didn’t die off in the Great Depression. In the 1960s and ’70s, there were also hundreds such enterprises.

“Things are going to happen, natural disasters. What better way to do it than collectively owned?”

And as the 2020 pandemic took hold, the worker co-op paradigm, with its labor-centered approach to business, held renewed appeal. Camille Kerr, the community organizer who conceived of ChiFresh, saw the co-op as an employment opportunity for formerly incarcerated women and a way to push ideas like non-hierarchical ownership, with each owner-worker sharing in the decision-making about, say, weekly menus. “The pandemic lifted up the need for us to focus on meeting each other’s needs, and to have infrastructure to meet each other’s needs,” says Kerr. “Things are going to happen, natural disasters. What better way to do it than collectively owned?”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Worker-ownership also often leads to better pay: Worker-owners earn an average of $19.67 per hour, according to the Democracy at Work Institute—more than seven dollars higher than employees of standard businesses. ChiFresh worker-owners pay themselves $18 per hour and are guaranteed 40-hour work weeks. And according to Manklang, worker co-ops also have a lower failure rate.

Earlier this year, California Rep. Ro Khanna remarked at a town hall at Santa Clara University: “Worker cooperatives can be part of the solution in building the working class and the middle class in this country.”

That’s not to say creating or running a worker cooperative is always easy. In Manklang’s view, banks and other funders also tend to act as barriers to co-ops in a way they don’t to traditional businesses. “The normal business model is ownership by one or two people, with people that work for them below,” she says. Since a business loan for a company tends to go to only one or two people, not a dozen, co-ops often find it tricky to access financing. The government tends to leave co-ops out in the cold as well: Federal grants may have sustained small businesses during the pandemic but didn’t do so for most worker cooperatives as most were not deemed eligible, according to reporting by ProPublica.

For the worker-owners I spoke with, these risks were all worth it, perhaps most of all for the sense of personal agency that being an owner confers upon a person. “We set our own wages and have meetings on a regular basis,” says Taylor, of her and ChiFresh’s other worker-owners. “I want to make the company work for me.”

“I want to make the company work for me.”

The Economic Hardship Reporting Project and Mother Jones sent six photographers to document co-ops in six regions of the country. The question underlying the assignment was both practical and utopian: What does it look like when ordinary people are their own bosses?

The Local Cooperative

If someone in Selma, Alabama, mentions the Local Cooperative, they’re really talking about two food-related co-ops that sustain each other: the Local Farm Cooperative and the Local Restaurant Cooperative. Both were established in 2018, two years after community members set a goal of building local solidarity. All members of the Local Farm Cooperative are on their way to becoming worker-owners, and many, like Alfonza Greer, have personal roots in Alabama agriculture. “I think I can grow as good as any farm could grow if I had the land to work with,” says Greer, a third-generation farmer. “I like the peace and quiet. I like to watch plants grow.”

Opportunity Threads

Opportunity Threads, a worker-owned cut- and-sew factory in Western North Carolina, specializes in customizing patterns and producing small runs of products. The mill belongs to the Industrial Commons, a larger network of worker co-ops launched in 2015 with the goal of building a “new southern working class that erases the inequities of generational poverty and builds an economy and future for all.” Employees are voted in as worker-owners after a 12–18 month vetting process. Most of the mill’s staff descend from Mayans who immigrated to the region from civil-war-ravaged Guatemala.

A Slice of New York

Kirk Vartan and his wife, Marguerite Lee, opened the first location of A Slice of New York in 2006, when Vartan quit a career in tech to open a New York–style pizzeria in Silicon Valley. Vartan and Lee eventually realized they wanted to achieve broader aims with their shops: to be more inclusive and less hierarchical with those working alongside them. The business became a worker-owned cooperative in 2017 and now has two shops, one in San Jose and the other in Sunnyvale.

The pizzerias have 27 workers, 13 of them cooperative members. Membership is open to all employees and is optional. To qualify, employees must work for at least one year or 1,200 hours; commit to working there for two years; pay $3,000, which can be paid in installments; and have their application accepted by 75 percent of members.

The Co-op Service Center

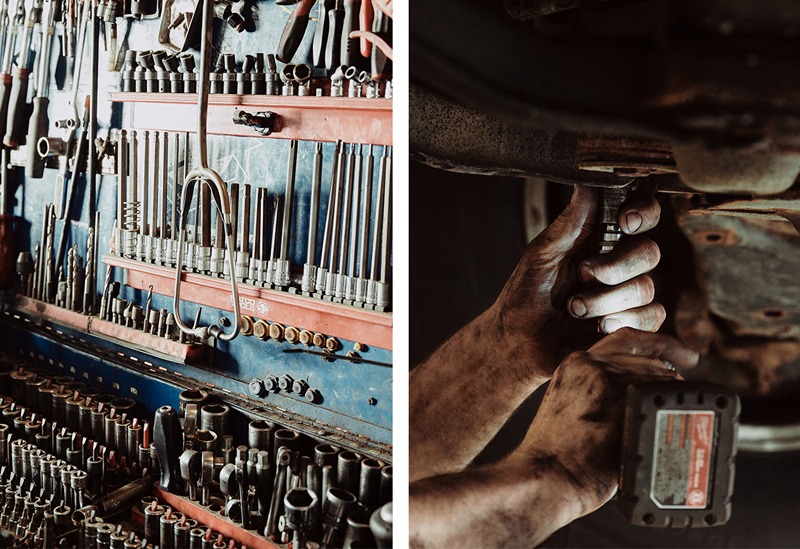

All day, 28-year-old Kegan White completes detailed tasks like fabrication and de-rusting as a technician at this cooperative auto service center in Norwich, Vermont. For his labor, White makes a competitive $23 an hour and receives dental and vision benefits, which he says are practically unheard of in the auto-repair industry.

The Norwich Service Station and its sister outlet, the Hanover Service Station in New Hampshire, are part of a large local cooperative that also includes three grocery stores and a community market and employs roughly 400 people.

This cooperative is different than the others featured in this project: Like thousands of other co-ops in the United States, it is a consumer cooperative, not a worker-owned cooperative. But it shares the communitarian ethos of worker co-ops. The service centers have featured a voucher program called Co-op Car Connections, whereby the mechanics do crucial repairs for car owners unable to pay, from oil changes to fixing a broken seatbelt. As COVID alighted, workers say their cooperative took care of its people. “The grocery stores did really good in the beginning of the pandemic and the company could have just kept all that money,” White says, “but they gave it back to the employees. I’ve never worked for a place that took care of their employees at that level.”

This project is a collaboration with the Economic Hardship Reporting Project with funding from Solutions Journalism Network. The full project can be seen September through December at Brooklyn’s annual Photoville festival. This article has been reprinted with permission, although some of the photo content has been altered.