Across the United States, significant achievement gaps persist between White and non-White students, particularly Black and Latinx students.

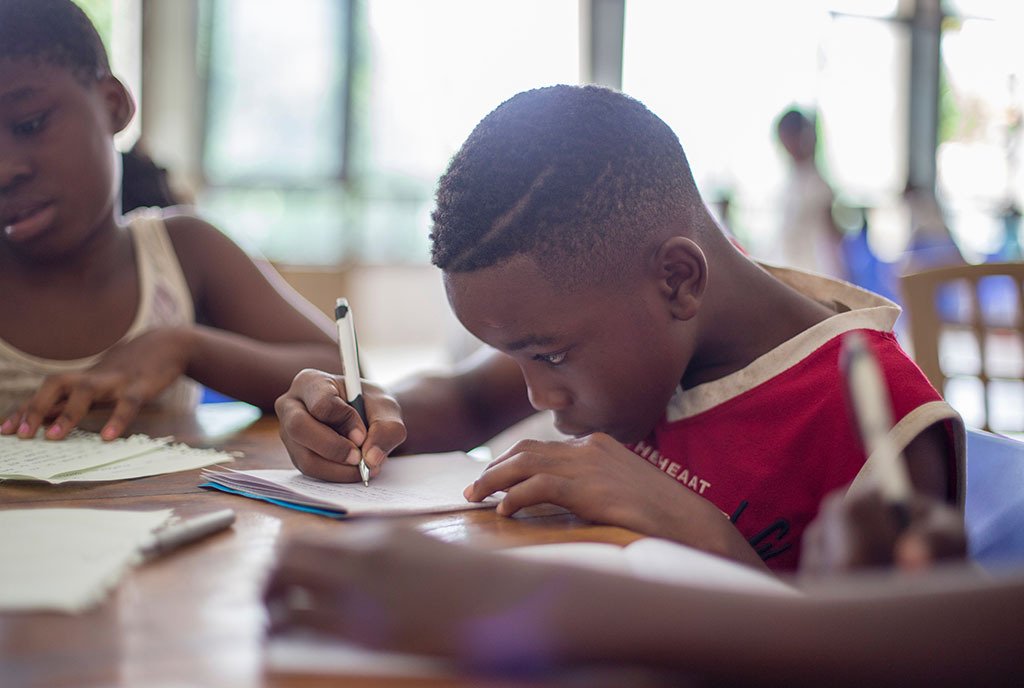

The goal of the program is to increase the educational performance of students of color.

A relatively new—and, at least in some corners, highly controversial—model seeks to diminish that imbalance by allowing students of color to participate in what at least one district is calling “affinity classes,” specially comprised of students of color and often taught by non-White teachers.

For several years, Evanston Township High School (ETHS), a public school in Evanston, IL, has run such a program, with some 200 Black and Latinx students signed up this year for math classes and a writing seminar intended to be populated by peers of the same race.

The goal of the program is to increase the educational performance of students of color and, more specifically, to see them participate and succeed at higher rates in Advanced Placement, or AP, classes in which students of color have been enrolled in persistently low numbers, school officials have said.

“Our Black students are, for lack of a better word…at the bottom, consistently still. And they are being outperformed consistently,” Monique Parsons, vice president of ETHS’s board of education told the Wall Street Journal this November.

According to the WSJ, district Superintendent Marcus Campbell told the ETHS student newspaper that the affinity classes were intended to create “a different, more familiar setting to kids who feel really anxious about being in an AP class.”

Whether the move will in fact result in better academic performance among Black and Latinx students is an open question—but the initiative and a handful of others like it around the country have already drawn criticism, including the ire of conservatives who accuse these school districts of, essentially, allowing and indeed promoting “segregation” in public schools.

“Our Black students are, for lack of a better word…at the bottom, consistently.”As one headline in the arch-conservative Washington Examiner ran: “Segregation is back, now pushed by the ‘woke.’”

Experiments with Affinity Classes

The idea of affinity classes is not entirely new.

In 2010, the Oakland Unified School District in Oakland, CA, created an experimental program for Black boys called the African American Male Achievement Initiative, in which several Oakland schools offered extra classes taught by Black men and intended for Black boys.

The program was introduced as an implementation of, or answer to, the My Brother’s Keeper Challenge, which was created by President Barack Obama’s administration to support community-led initiatives designed to improve the educational attainment of young men of color.

A 2019 study by Stanford’s Center for Education and Policy Analysis found that the program was successful in substantially reducing the dropout rate for Black boys in several Oakland schools.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The school district of Minneapolis, MN, has also experimented with similar programs.

The legacy of school segregation hangs heavily over the push for such affinity classes.

But while such models have existed in various forms and in various places for decades, the movement behind such models has come under new fire in recent months, with conservative groups openly invoking the “S-word” and others in educational academia voicing less aggressive concern over such programs.

The recent Wall Street Journal piece quotes Max Eden, an education researcher at the conservative American Enterprise Institute criticizing such models as working against what he describes as the inherent virtues of “integration.”

“Integration is a positive social good,” Eden told the WSJ. “We want students to be colorblind and to treat each other only on the basis of who they are as human beings.”

Tenuous Legal Ground

The legacy of school segregation—not to mention racial segregation writ large—hangs heavily over the push for such affinity classes, which walk a sometimes tenuous line between laws barring segregation and racial discrimination on the one hand and the drive by educators to implement models that benefit minority students on the other.

An attempt by the school district of Wellesley, MA, to create race-based “affinity groups” within its schools was met by a federal lawsuit filed by an out-of-state conservative group, Parents Defending Education, that claimed the groups violated federal laws barring racial segregation.

As reported by Boston.com, the group argued that “because racial affinity groups divide children by race, these groups foster racial division.”

The town of Wellesley settled that lawsuit, agreeing to make clear that the affinity groups were open to all students.

Federal guidance, meanwhile, remains vague on the subject. On its website, the US Department of Education states, “School districts may not segregate students on the basis of race, color, or national origin in assigning students to schools,” but contains no overt language on the formation of the kind of affinity classes being piloted in schools like Evanston Township High School.

And so the future of such affinity classes remains uncertain. To proponents, such models offer at least the potential to finally bridge long-standing achievement gaps that have seen Black, Latinx, and other students of color consistently behind their White peers.

To opponents, especially in this time of partisan and cultural divide, they offer something else: a target.