July 20, 2018; CBS Moneywatch

In what may be the biggest US coordinated enforcement of charity standards ever, last week, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the National Association of State Charity Officials (NASCO), and law enforcement officials and charity regulators from 70 agencies in every state, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, and Puerto Rico announced they took or would take more than 100 legal actions against 85 fraudulent organizations promising to help veterans and service members. This action is a welcome crackdown on a longstanding problem that has cost veterans and the charitable sector dearly over the years.

“Americans are grateful for the sacrifices made by those who serve in the U.S. armed forces,” said FTC Chairman Joe Simons in a prepared statement released on Thursday. “Sadly, some con artists prey on that gratitude, using lies and deception to line their own pockets. In the process, they harm not only well-meaning donors, but also the many legitimate charities that actually do great work on behalf of veterans and service members.

NPQ has long identified this subsector of charities as a playground for fraudsters. In many cases, the fraud entails the use of telemarketers who make calls appealing to the public for support for veterans and then plow the large majority of that back into fundraising and the salaries of a few organizers. At the end, in too many cases, little to nothing is left for veterans.

But there are many variations on this theme. In a 36-page list, enforcement actions are detailed. California lists 11 all on its own and Georgia lists seven. Enforcements target nonprofits, such as Help the Vets, and private fundraisers which fraudulently seek donations online and through telemarketing, direct mail, and personal contact, whether door-to-door or at retail stores. Appeals falsely promise to help homeless and disabled veterans; to provide veterans with employment counseling, mental health counseling, or other assistance; and to send care packages to deployed military personnel.

Some counterfeit charities falsely claimed that donations would be tax deductible; others used deceptive prize solicitations. Some legal actions were against charities engaged in flagrant self-dealing benefiting those running the charity; others focused on private enterprises that made misrepresentations on behalf of veteran charities or stole money solicited for the benefit of veterans and military personnel.

This initiative reflects a new enforcement model, reported on in the summer 2016 edition of Nonprofit Quarterly, that relies on state charity offices, sometimes in league with the FTC, coordinating action—even across state lines—at a scale capable of taking down the malefactors running charity scams or providing telemarketing services to those that do. Scams like these tend to occur in agencies that say they’re serving a highly sympathetic population, whether it’s cancer patients or first responders.

NPQ started reporting on what became the coordinated action of the Cancer Charities Fraud case in 2013. It took until 2016 before it was finally resolved, but the enforcement model used then is being employed here, at a higher level. As you may notice, the IRS is absent from the array of collaborators for now.

So why veteran’s charities? Scoundrels love the military. NPQ has reported on too many such cases (including here, here, and here):

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Help the Vets, for example, took in more than $20 million with claims that it would use the money to assist veterans with grants, medical care, suicide prevention programs and therapeutic retreats. In reality, these programs were fabricated. The money went to the organization’s founder and paid fundraisers, the federal agency said.

Likewise, a group of related organizations including Veterans of America, Vehicles for Veterans, Saving our Soldiers, Act of Valor and Medal of Honor were all operated by a Utah man named Travis Deloy Peterson. According to a government complaint, Peterson used robocalls to encourage individuals to donate their cars, boats, real estate and timeshares, which Peterson sold at auction. Although Peterson’s robocalls assured donors that their gifts were tax-deductible, none of Peterson’s companies were tax-exempt nonprofits.

Whether or not they are officially exempt organizations, they are charities in name only, almost always names that mimic legitimate nonprofits. It’s a particularly ugly crime that steals tens of millions of dollars from genuine causes. What is so pernicious about scams likes these is that the altruistic element that makes them so disgraceful is what makes them so effective—people do care.

Taking flagrant advantage of such worthy causes is likely to continue as tools and elaborate data systems used to target donors become ever more sophisticated and effective. Our sector needs to stay vigilant and work with state and federal regulators to safeguard the public trust in work.

Peter O’Rourke, acting secretary for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, said the real tragedy of these bogus veterans’ groups is they not only steal donor’s money, they steal their trust.

“They discourage contributors from donating to real veterans’ charities,” he said.

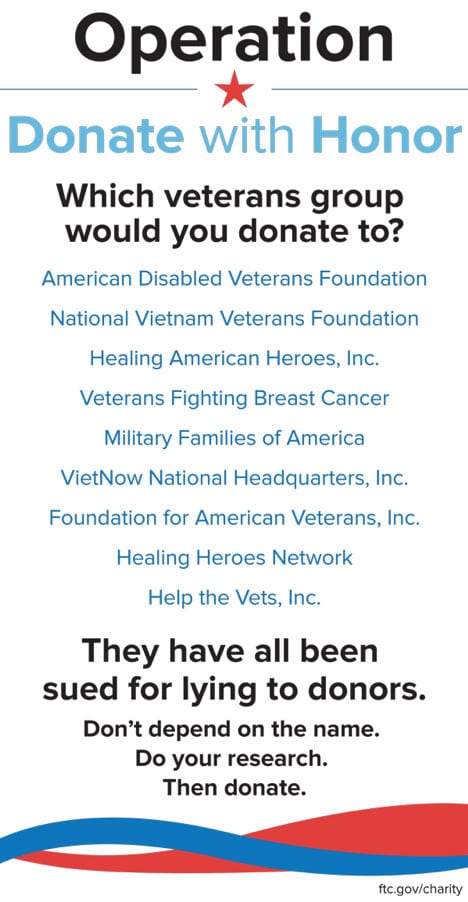

The FTC has also initiated a consumer education initiative called Operation Donate with Honor (including this video) to help consumers distinguish between charitable solicitation fraud and legitimate appeals for support. Here is one sample of what that will look like:

The shame of all of this, of course, is that legitimate veterans’ charities may be faced with skepticism by the public when they request funds. On the other hand, one hopes they’ll face less competition from those who seek to dupe the public in the name of people who have earned that public’s care and attention.—Jim Schaffer and Ruth McCambridge