Vital Energies

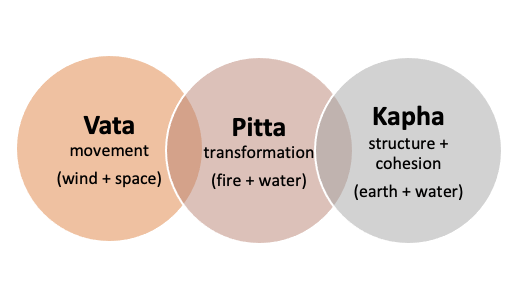

In Ayurveda, one of the world’s oldest healing systems, the word doshas refers to the vital energies that animate life. These energies consist of specific combinations of the five basic elements: space, wind, fire, water, and earth. Vata is the energy of movement, made of wind and space. Pitta is the energy of transformation, made of fire and water, and kapha is the energy of structure and cohesion, made of earth and water. I share my story here as an unfolding of these energies, followed by an inquiry into how we might use this ancestral knowledge to build healthier organizational and movement cultures. I focus on expanding our views on fire, which brings so many of us into justice work but can also wreak havoc and turn us against each other. Ayurveda helps us become more masterful at the interplay of energies surrounding fire, giving us a vision for healthy and vibrant ways of moving toward liberation.

Fire

I’m a hothead. In my family, I was known as the quiet one, the one who never spoke, the invisible person in the corner . . . until I was not. Even though they all were more boisterous in the day-to-day, it was me who they were afraid of because I would explode—out of nowhere. Fire stirred in me. It caught me by surprise, taking over when I least expected. Maybe it was because I was the third child in a noisy house. Maybe it was because I moved to a white school in a white place in third grade, where my own teachers would ask me what tribe I was from, and my most common yearbook greeting was, “You’re okay for an Indian.” Maybe because of the way men were centered in my house and women worked until their spines broke. Maybe it was because I got terrible acne that made me withdraw from my body. Or maybe it was because that was just my nature, the stuff I was made of. I didn’t know, but when I erupted out of my quiet girl mode, it was on. I would run out of the house with no shoes on, crying and screaming until I realized my runaway plan was not that solid. I threw things sometimes, punched walls (once so hard I made a hole in the bathroom door), all while getting the “Most Kind” award at school. Fire was my secret life.

I wondered, can an Indian girl who can’t ride a bike like the white kids, with a face full of acne, even get mad? Did I have a right to the anger that burned inside me? Somewhere along the way, I learned the answer was an unequivocal “no.” I was praised for my quiet and compliant nature, making my eruptions an even greater betrayal. I imagined my aunties thinking: “What took over this good Indian girl? Was it American culture teaching her bad values? What a shame. I guess this is the cost of life in this god-awful place. Karma. What can you do?” There was never any investigation into my rumblings. If I could have willed my fire away, I would have, but I didn’t know how. Nor did I see any good examples of what you do with fire. My dad chose escapism; my mom suppression. My brother, sister, and I would fight constantly. Yet, in some implicit way, fire was allowed in my family even when we had no idea how to handle it, and this subtle permission opened a crack for expression.

Over time, my secret life began to make public appearances. When my 5th grade teacher, who knew nothing about me, gave me a bad grade for not speaking loudly enough in what was the most terrifying act of public speaking I had ever done, I got pissed. Because I didn’t have much of a voice, I decided to create chaos through the alarm on my watch. I set it to beep just as class ended and recess began, when everyone was moving around. No one knew where the annoying, loud noise came from. They never suspected me. It drove them crazy, and a sinister laugh bubbled through my being. It was SO satisfying . . . a moment of life in a sea of dullness.

Another time, a bully in the girls’ locker room told us to shut up because she wanted quiet. I moved out of her sight and slammed my locker shut as loud as I could. She exploded with anger, and I ran out without her knowing the culprit was me. When my white evangelical high school teacher made us read the Bible in English class then scolded me for trying to interpret it—insisting the Bible was “just literal and nothing else”—I started cheating on tests. My fire fought back as I tried to keep my good Indian girl act going. It had wisdom that I did not, like a headless monster searching for the truth.

Wind and Space

When I got to college, I finally got some direction for the burning in me. My first day, my professors asked us to read Jorge Luis Borges’s La Biblioteca de Babel, a literary piece of magical realism that riffs off the Tower of Babel, the same part of the Bible that my high school teacher said had no deeper meaning than was on the page. My just-out-of-high-school mind had no clue what Borges was saying. Half of the other students must have felt the same because they dropped the class at break. But for me, this was a moment of victory. Damn them, I knew there was more. My fire gave me courage to remain in the unknown, to risk failing in pursuit of a deeper truth that until now I did not know I had ached for. That day, Borges opened the door for me to enter a different universe, a library of knowledge filled with chaos and order that transformed me and gave space and wind to my fire.

College ignited my mind and gave me words to understand and describe my experiences. The wheels clicked when I finally understood that systems of oppression shape individual experiences in patterned ways. Instead of being pushed around by my fire, I began to use it. I fought for an Asian American Student Union to replace a club led by a white man and Indian woman called ASIA (Any Student Interested in Asia), where white folks shared slide shows of their trips through Nepal. My first moves in this new dance with fire were sloppy. I wanted to join MECHA (Movimiento Estudantil Chicano de Atzlan), which was more my political vibe, until my Chicana friends, who led the group, reminded me I was Indian.

I got angrier and refined my analysis as my emotions burst forth. Activism healed me, gave me purpose and community, and yanked my voice out from inside me. I still fought, punched, and screamed, but now through words and tactics. I battled professors, checked my own family, and little by little, removed all the white people from my life. For the first time, I cared about and exceled at school instead of just being the “dumb of the smart.” My mind became bright but dangerous.

Sometimes, my critique would go on overdrive. I remember, when I was studying Franz Fanon in an African politics class, a discussion with my white professor, with whom I kept going back and forth until he said, “That’s just a verbal game.” I responded, “Isn’t that all there is?” and he said, “No, people die.” Checked, I knew there was something to that, but I went on with my education in deconstruction and post-modernism until I lost sight of how to construct something. I was so good at breaking things down—it was satisfying to burn things—that I no longer could build.

I graduated, with what Indian immigrant parents consider a completely useless degree in comparative literature. Following prudent advice from an eccentric philosophy professor, whom I adored, to “live a little” instead of diving straight into graduate studies, I moved home and got a job, entering “the real world.”

Earth and Water

I worked as an English as a Second Language teacher for a year then went to California for further education. After accumulating more debt and graduating with my master’s degree, I worked one year at an educational software company, then moved to San Francisco, where I couldn’t find a job. “Underqualified and overeducated,” with no connections in the city, I was not an appealing candidate. I wanted to do social justice work but couldn’t figure out how to break in. I was also filled with doubt and self-critique because of my well-trained deconstructing mind. My fire met earth, and my first steps into the real world were humbling.

My roommate worked at Cesar Chavez School, down the block from our house in the Mission District. She said they had an opening for a Healthy Start Coordinator funded by a federal grant, no benefits and full time. Perfect, I thought. I was not the school’s first choice, but other applicants turned down the job, and I was in. Chavez was the first radical community I was part of. There, I saw how fiery people could come together around politics, love, and a shared vision not to engage in verbal battles, but to, as Amilcar Cabral said, “[fight] to win material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives go forward, to guarantee the future of their children.” I coordinated the school’s support services (afterschool program, parent center, health screenings, etc.). In the process, I was trained in community organizing by movement folks.

Pilar Mejia was the principal, my mentor, and a long-term organizer in the community. She told me stories of how they buried arms under Dolores Park back in the day to support Indigenous revolution, and she led our school like the radical newspaper, Tecolote, that she had come from—with a collective leadership structure that distributed power and a system of consensus-based decision making. Our public school in “the hood” had a Spanish-bilingual, Cantonese-bilingual, and African-centered program, and the only deaf program in the city. We ran our meetings in four languages and built power across diverse communities to advocate for our predominantly working-class families who were facing gentrification. We were fighting Prop 209 and 227, food policies that led to the terrible state of our school food, anti-Black suspension and expulsion practices, the school-to-prison pipeline, and much more. A pulsing community hub, the school was open day and night.

Many of us were (and still are) friends and movement partners, not just colleagues and co-workers. We partied to salsa, bhangra, and world music. We did libations at each staff meeting. When in conflict, we used the same mediation process that we asked the kids to use, with a commitment to living our values. There was so much love and connection across communities usually fragmented into tiny categories defined by the politics of oppression. The school wasn’t perfect, and like any community, we had our drama and chisme, but it was special both in its ambition and structure.

Earth brought two things to my fire. First, it diminished my hubris. White supremacy teaches us to value the mind over all else, especially in the Ivory Tower. But the mind without experience is unanchored and unwise. While wind moves fire, earth grounds it. Second, it brought structure to my fire. There were many thoughtful ways of doing and being at Chavez, carefully built to reflect our values, from how we ran our meetings and made decisions to how we responded to conflict.

This thoughtfulness turned what was once Hawthorne School, an ordinary, run-down school in a working-class, Latinx neighborhood, into Cesar Chavez School, with the brightest mural and most bustling energy on the block. The other part of the equation of Chavez School was community, connectivity, and love: water. Our relationships were as important as our work, and we spent time cultivating them, embracing diversity and moving beyond tokenized gestures of inclusion. This brought cohesion to the flames of our collective fire.

Lately, I have been watching superhero movies with my son, Asim, and have learned that every hero has an origin story that’s key to understanding who they are and their powers. Chavez was my origin story in justice work and shaped the next decades of my life as a builder of radical communities. It’s where all five elements came together for me, setting a path for my future: fire, wind, space, earth, and water. And it’s where I gained a vision for what is possible when those elements find balance.

The Nature of Fire

Over the years, I have worked to build many radical communities in which we found ways to balance the doshas of movement, transformation, and structure to breathe life into new ways of being and new possibilities for our world. And life has also presented me with lessons on imbalance: when these energies don’t line up, when there is too much of one or too little of another, and things don’t work in our favor.

This is what I see so much of in organizational and movement culture—vital energies out of whack, especially the pitta energy of fire. I’m not the only hothead I know in this work, and I love my fiery peers. However, I believe that the combination of too much fire and too much headiness contributes to the toxic cultures of many workplaces devoted to justice. “Burnout” and “meltdowns” are common in the best of groups these days. So much in our world needs disrupting, breaking down, and destroying that we turn to fire over and over. Abolition work requires it. But fire is a tricky energy that can wreak havoc and turn inward, especially if unbalanced by other energies. In fact, the literal translation of the word dosha is “fault,” “problem,” or something easily “disturbed.” Our ancestors built a warning right into its name.

Adding to the heat, a lot of head—disembodied white-supremacist habits of mind sharpened in academia—makes matters worse. The result is a culture of unbearable, endless critique. Destruction on overdrive. Our work as organizers is to expand the universe of people who care about each other and the issues that face us, not to win intellectual battles at the cost of relationships. Both fire and mind are fast-moving, sharp, penetrating forces in Ayurveda. In partnership and unchecked by other energies, these forces can tear at our unity and the larger community we need to win.

The other day, I was on a call during which two like-minded, long-term organizers met for the first time. By the second sentence, one had decided that the other’s use of the phrase, “pick your brain,” was reason for not continuing the relationship. A younger organizer, on a separate occasion, showed me a tweet that “canceled” her; the tweeter claimed she was posing as a member of a marginalized community, trashing her in front of thousands of followers. I have participated in takedowns, when we called out abuses of power by leadership through e-mail message after e-mail message that allowed for no other narrative to form. Flames erupted. People got hurt, and our efforts crumbled, often never to re-emerge, resulting in big losses for our movement. In all these examples, we were all BIPOC and had experienced oppression that sparked our commitment to justice. We were all on the same side. Fire brought us to this sacred work, and fire took us out.

The other day, I was on a call during which two like-minded, long-term organizers met for the first time. By the second sentence, one had decided that the other’s use of the phrase, “pick your brain,” was reason for not continuing the relationship. A younger organizer, on a separate occasion, showed me a tweet that “canceled” her; the tweeter claimed she was posing as a member of a marginalized community, trashing her in front of thousands of followers. I have participated in takedowns, when we called out abuses of power by leadership through e-mail message after e-mail message that allowed for no other narrative to form. Flames erupted. People got hurt, and our efforts crumbled, often never to re-emerge, resulting in big losses for our movement. In all these examples, we were all BIPOC and had experienced oppression that sparked our commitment to justice. We were all on the same side. Fire brought us to this sacred work, and fire took us out.

Agnidev, the god of fire, is one of the oldest Vedic gods.1 There are more hymns to him than to any other god in the pantheon. He is depicted with two heads that represent two aspects of fire: creation and destruction, both necessary for life. His three legs represent the physical body, the mind, and consciousness. Agnidev is known as the mouth of the gods, the bridge from the lower to higher self, and the transformative energy that gets us there.2

But this god of fire can easily get out of control. In one well-known story, the god is cursed by a sage to “swallow everything in his path.” Upset by this curse, he goes into hiding until the gods placate him by complementing his curse of total destruction with the power to purify everything that passes through him.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As we seek transformation, we play with fire, but do we know how to worship it? I have seen, in myself and others, a kind of recklessness with fire. It feels good to destroy in a world full of hate, but this easily gets out of control. “Pick your brain” is white- supremacist, patriarchal language that should be uprooted. But if we use fire to publicly shame our like-minded peers toward this outcome, are we really winning? Without a relationship that can hold this fiery critique, isn’t such outing just another type of transactional brain work?

I am not writing off cancel culture entirely. It has its place. But more often than not, such cancelling is more of a trauma response than a path to transformation, a kind of disembodied scream into the darkness and anonymity of a digital world. It feels good to light fires when we are in pain, but is this strategic? Coordinated? Or just individual acts of arson that do more damage than good? A curse of Agnidev?

When we burn down organizations because of abuses in leadership, do we have alternative structures to offer? Or are we destroying without creating? Are we verbally deconstructing, or are we constructing new material ways of being? The destructive work of Agnidev rightly demands much time and attention. Yet, the creative aspect also need attention.

As the abolitionist and Afro-futurist radical imagination tells us, we have to create a vision for what comes next. “Swallowing everything in our path” is a curse, not a blessing, and fire jumps out from where we least expect it. At best, it’s a doorway to higher ways of being. At worst, it’s a headless, insatiable monster that consumes everything it encounters. How do we tend to it? How do we seek its blessing in body, mind, and spirit?

Ayurveda: Toward Healing and Balance

Ayurveda offers guidance. A new love of mine, it is an old science of my people. A few years back, when my friend and colleague, spring opara, designed a leadership program called “Self-Care for Black Women in Leadership,” with an emphasis on returning to ancestral wisdom, I thought maybe I should explore my own inheritance. Outlawed in India under colonial rule, Ayurveda is making a resurgence on the heels of a commercialized yoga movement. For my parents’ families, it was common sense, passed down through the generations for millennia, even when forced underground. Like all knowledge, however, it’s important to understand how colonialism and capitalism influence its expression, especially given that the Hindu Right has co-opted these traditions as proof of Hindu supremacy and justification for violence against other, marginalized groups. Despite this problematic context, at its core, Ayurveda is rich and ancient indigenous wisdom.

What blows my mind about Ayurveda (in addition to the fact that it explains why we ate ghee in my house and why my great grandmother left rice in the moonlight before cooking it) is its expansiveness and range. One of its first lessons is the origin of the universe and Sankhya philosophy, followed shortly thereafter by, “and therefore, this is what you should eat.” It breaks down the reductive binaries that white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy rely on to keep us isolated from each other and fragmented in our thinking. Science is also poetry and spirituality. Mind is body, and body is mind. All of us are manifestations of consciousness (purusha) and matter (prakriti). Not all of what is written in the Ayurvedic texts is “progressive” in the modern sense, as they are also products of time and culture, but the more I immerse myself in this pre-capitalist, pre-colonial worldview, the more I expand my thinking beyond oppression’s training.

Three Energies, Not Just Fire and Transformation

So, how has oppression trained us to think about and use fire, and how might Ayurveda see it differently? First of all, oppression has fragmented our thinking. Many ancient traditions agree on the power of opposites and the goal of balance: the sun and the moon, thinking and feeling, individual and community, and so on. Yet, greed-driven systems of power favor and overvalue one side of the equation over the other: sun over moon, thinking over feeling, individual over community. Suddenly, there is a better and worse, a rich and poor, a good and bad—how convenient to what bell hooks refers to as the “imperialist, white supremacist, heteropatriarchy.” Reductive binaries create conditions for claiming false superiority (eg, “men are superior because they are rational thinkers” while women are relegated to the “inferior world of emotion.”)

So, we are exposed to only half of the story. But the other half doesn’t disappear; it goes underground. Here, the missing part of the story is fire’s relationship to the other vital energies, the ones devalued in our society because they don’t align with ego and greed. In Ayurveda, pitta energy at the level of the mind is associated with goal setting, decisiveness, problem-solving, intelligence, courage, and boldness—all of which are assigned high value in our current male-dominated, authoritarian systems of oppression. On the other hand, vata, the energy of movement made of wind and space, is associated with creativity, intuition, communication, inspiration, and adaptability—concepts that are gendered as feminine, made invisible, and undervalued. Kapha, the energy of structure and cohesion made from earth and water, is associated in the body with fat and other building blocks we need. Kapha brings strength, stamina, compassion, memory, and connectivity to the mind and body. It also represents love. In fact, it is a carrier of pitta because without kapha, the flames would be too intense to perform their functions (eg, stomach acids would burn up the lining if no liquid was present). Without love, there is no transformation.

What distinguishes good fire from bad fire in Ayurveda is their relationship with these other energies. When pitta dominates, it diminishes kapha, emptying our storehouses of energy and resulting in burnout. If kapha dominates, it can snuff out our pitta, leading to dullness, inertia, and lethargy. Vata is often the main instigator of disease—too much movement and change can throw everything off. All this happens at the level of mind and body, and since these are part of a continuum, when one is affected, the others go off balance. Below is a chart which shows what pitta energy looks like when balanced and imbalanced by the other doshas in body and mind.3

Pitta: The Energy of Transformation

| Mind | Body | ||

| Balanced | Imbalanced | Balanced | Imbalanced |

| Goal-setting inclinations | A tendency to be hostile, angry, and controlling | Strong powers of digestion | Excessive body heat |

| Good problem-solving skills | Impatience | Vitality | Digestive problems |

| Keen powers of intelligence | A tendency to exert excessive effort to achieve goals | A bright complexion | Vision difficulties |

| Decisive/focused | Passion or emotion blurs powers of intellectual discernment | Oily skin | Inflammation |

| Boldness and courage | Judgmental | Easily gains or loses weight | Diarrhea |

| Confident | Jealous | Medium body frame/weight | Ulcers and GI disorders |

| Strong memory | Arrogant/egotistical | Moderate pulse rate | Excessive thirst |

| Organized | Overly competitive | Moderate sleep | Skin disorders (rashes, acne, etc.) |

| Joyful | Needs attention/loud and extroverted | Fine hair, bald | Hepatitis and liver disorders |

| Strong leadership abilities | |||

| Easily grasp new ideas and concepts | |||

How do we heal and reach balance? The first step is to unlearn the fragmented thinking that forces our gaze on fire alone and make visible the value and work of vata and kapha. As the feminist movement teaches us, social and emotional labor are the backbones of our movements. These are part of the domain of vata and kapha. To see fire but not see its connections to wind, space, earth, and water is reckless. It reinforces the dominant notion that change only happens through battle. This is not to diminish the role of fire, but to put it in its proper place.

Next is to gain greater awareness of our own personal make up of these energies, or prakriti, as a starting point for self-care. Each individual has a unique mix of vata, pitta, and kapha. Most of us are dominant in one or two of these energies and need to use this as a reference point for the lifestyle choices we make. I am predominantly pitta and vata. Unprocessed thoughts and feelings stemming from my experiences with power and oppression combined with lifestyle and food choices led to an imbalanced fire, which caused my anger and acne issues. This imbalanced state is called vikriti. Metabolizing my early experiences through study, combined with more solid daily routines and healthy, balanced eating, has made a huge difference. My healing came from the introduction of opposite energies (eg, cooling foods for an overheated body, more space when there is too much mental clutter). Since we are always in a state of change, Ayurveda is a constant dance of finding dynamic balance of the doshas to move from vikriti to prakriti, or imbalance to balance.

At the group level, we need to appreciate and understand each person’s unique nature and how our collective energies can bring health and vitality as opposed to competition and distrust. A common leadership development activity is a styles assessment during which people decide whether they are more of a visionary, implementer, or counselor. The activity does not address power or oppression, but it almost always leads to big aha’s. The most impactful part of this activity is when participants tell a person of another leadership style what drives them crazy, revealing the tension that is natural between opposites, the narcissism we have about our own styles, the ways we have been trained to value some but not others, and the gifts we need from each leadership style to achieve balance. When I discovered Ayurveda, I finally understood the indigenous roots from which these kinds of activities are stolen. In our organizations and movements, we need not just fire, but a dynamic balance of vital energies and the gifts that come from opposing forces.

We also need to cultivate an understanding of how each of these energies look and feel in our work for change. For example, I spend a lot of time in the nonprofit industrial complex (NPIC) playing the funding game—packaging ideas and visions for sale so we can do the work we want. I have also long participated in South Asian activist work as a more direct connection to grassroots change. I am an organizer for the Bay Area Solidarity Summer (BASS), a political camp for South Asian youth that we put on each year as part of a base-building effort. The inspiring political vision of this work—building solidarity among young Indians, Pakistanis, Nepalis, Bangladeshis, and other Desis from the diaspora across class, caste, religion, and gender differences and exporting this solidarity back to the homeland to confront the politics of hate exported by the Hindu Right—reminds me of what is possible when the creative energy of vata breathes outside the NPIC. It helps me see that our fire energy is often pushed into a tailspin by the whims of funders, who make us lose track of what we are about. When we lose sight of our inspiration and plod along a set of deliverables and timeline, we more easily turn against each other. Maybe we need to introduce more vata energy through creative, uncensored conversations about our vision, giving more direction to our fire? The antidote is the introduction of other energies.

With kapha, we need to examine our connective tissue—especially in these isolating times of the pandemic. What holds us together? One of the relational practices I have used in many organizations is a coaching tool called Designing Alliance. It is essentially a menu of questions about partnership. How do we want to be in conflict with one another? How do we want to hold each other accountable? How do we want to champion each other? And so on. These are one on one conversations that happen monthly or quarterly and help participants understand each other and design new ways of being instead of defaulting to dominant culture. This practice has gone viral almost every place I’ve used it, building cultures that hold fire and community simultaneously. It’s a kapha practice—facilitating structure and cohesion.

For pitta, one of the most important aspects of care is paying attention to digestion of food, as well as thoughts and emotions. This is a key function of fire in Ayurveda. When our fire is imbalanced, it can lead to toxicity or ama, undigested elements that clog up our channels and cause disease. I see so many unprocessed thoughts, feelings, and trauma in “toxic” work cultures. The quantity and pace of oppression leave little room to process and digest, and people end up dumping unresolved tensions on each other. We need to build the capacity of our digestive fire, individually and collectively, precisely because of the speed at which our world moves. In Ayurveda, healthy fire is one of the main sources of life.

Volumes of ancient texts are dedicated to the concepts of agni and ama—two of the most fundamental concepts of health in Ayurveda. One text describes the one-third rule. To digest properly, you need one third food, one third liquid, and one third space. As a facilitator, I think the same is true in how we convene, build relationships, plan, and strategize. We need one third content, one third connection and cohesion, and one third empty space for digestion. Instead of just plodding through agenda items at a mile per minute, can we select two or three juicy topics and focus on building our ability to share deeply, make meaning, and engage in generative conflict? Can we build a strong, stable, and efficient digestive fire through which even the most difficult of issues can lead to deep insight and strategic direction? In Ayurveda, you are not what you eat, but what you digest. The quality of food is less important than the power of your digestive fire. To remove toxicity from our cultures, we don’t need to change every negative thing that we ingest, but rather improve our ability to transform what we ingest into nourishment.

Last Thoughts

In my early years, I wondered where my fire came from. Now I know it came from painful experiences that I couldn’t digest. It came from the stuff I am made of, my prakriti. It came from what I ate, which aggravated my pitta. Later, I understood that I can’t just use my head to give direction to my fire. I need to use my heart and body. I’m still fiery but have more ways of understanding this fire and honoring and balancing it. I wish the same for our movements. I want to reframe the dialogue on toxicity in our work cultures through engagement with Indigenous knowledge. Ayurveda is just one source of such knowledge. I hope we will draw from a deeper well of knowledge to build unity and confront our times. Let us build compassion for ourselves as changemakers and become masterful in the art of fire.

Notes

- https://hindupad.com/agni-namavali/.

- Lad, Vasant. Textbook of Ayurveda, Vol. 1: Fundamental Principles of Ayurveda. (Albuquerque, NM: The Ayurvedic Press, 2001) 82.

- https://vibrationalayurveda.com/pitta