September 26, 2020; New York Times

When a superstar suggests you take an online course with him, would you be tempted to join in? More than 64,000 people signed up to take “Indigenous Canada,” a free online course, when the Canadian star of Schitt’s Creek, Emmy award-winner Daniel Levy, told his fans he was taking it and they might want to join him. This was more than had completed the free program offered by the University of Alberta in Edmonton in its three-year history.

Why this course? And why now? As Levy explained in his Instagram post, his reason for taking the course was “because if 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that we need to actively relearn history.”

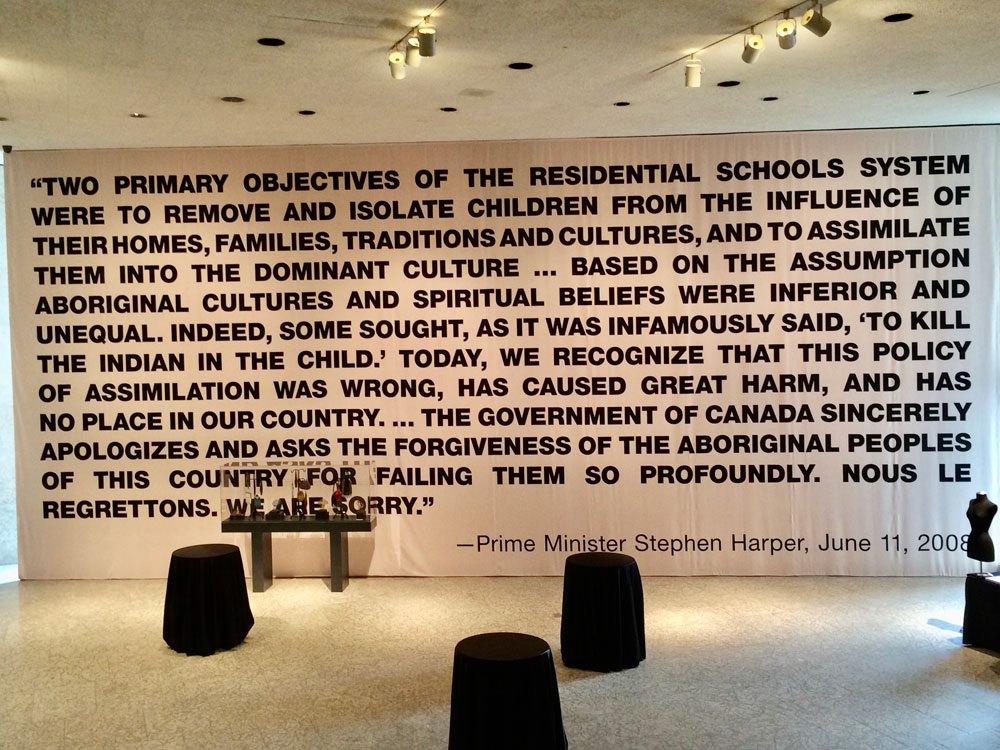

Canada, like the United States, struggles with how to deal with its systemic racism against the country’s Indigenous populations. Many Canadians, prompted in part by their country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, issued five years ago, are searching for ways to rebuild relationships with its First Nations populations.

The 12-week course covers history and contemporary issues of First Nations peoples in Canada and is totally online with no interaction with instructors. This was not enough for Levy, however. He wanted some real-time interaction. He arranged a broadcast study group every Sunday afternoon where he can meet virtually with professors from the university to discuss what was covered that week. This is an opportunity to interact and go deeper into Indigenous stories, perspectives, treaties, and more. And each week, thousands of people watch these sessions.

It was not Levy’s fame that got him this gig; neither of the professors who developed this course knew who he was or had ever watched his show. Tracy Bear, an assistant professor of Native Studies who developed the course, got an email from Levy and shared it with her colleague Paul Gareau, a Métis scholar who runs the online course. (The Métis are people of mixed European and indigenous descent in Canada.)

Bear and Gareau decided to take Levy’s word that he really wanted to reeducate himself and bring others along with him after checking out his social media accounts.

They also saw this as an opportunity. It comes at a time when the university was slashing positions and merging faculties in light of provincial funding cuts. Perhaps this venture might elevate their work.

“We never have this kind of coverage for anything we do,” said Gareau. “People love Dan Levy so much.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As Levy and his followers examine and relearn Canadian history, a similar push is under way to reexamine the history of the United States with an eye to lifting up the experience of Indigenous populations and enslaved people. For example, the 1619 Project in schools looks openly at the horror and long-standing impact of slavery on every aspect of the US. Others are, like Levy in Canada, developing new curricula and materials on Indigenous people and a more accurate history of both Native Americans and Black Americans.

What has come from this effort by a major celebrity to raise his own knowledge level and bring others along with him is recognition that it works.

“If 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that we need to actively relearn history—history that wasn’t taught to us in school—to better understand and contextualize our lives and how we can better support and be of service to each other,” Levy says.

For Bear and Gareau, it has also opened the door for greater interest in expanding their area of study to more students. Bear opens each of the weekly discussion sessions by lighting a piece of sage and passing the smoke over her face, arms, and hair in a “spiritual cleansing.” It opens the sessions with an Indigenous way of knowing and learning as with whatever historical content will be discussed. And each of these sessions is viewed by thousands of students on Zoom, eager to absorb more. As Gareau says, “The Indigenous articulation of knowledge is through experience and visiting.”

“A big part of what I love about this thing we do with Dan,” he adds, “is we are visiting.”

Perhaps this is what it takes to push people to take on a hard subject and deal with something that makes them uncomfortable: someone they admire saying, “I’m going to do this, come with me!” But if that is what is needed, then one might hope that Levy’s example will be replicated by others in Canada, the United States, and elsewhere.

Bear notes that Indigenous history in Canada cannot be fully conveyed in a single course, and she and Gareau hope to create four more online courses about structural racism and stereotypes, from an Indigenous perspective. And this time, they will charge for the courses.

Levy has become their ally. And, as Bear said in an email to the New York Times, “The facts are these: Due to Dan Levy, more people than ever are engaging with this difficult history, learning not only about Indigenous people’s challenges, but our resiliency and strength.”—Carole Levine