July 26, 2020; National Public Radio and Artnet News

The government in Washington has ground to a halt while trying to figure out how to help people survive the economic downturn that COVID-19 pandemic has brought. Millions of people face the loss of the increased unemployment benefits that had been part of the recent stimulus package. Whole industries have been shut down to prevent the spread of the disease, leaving workers without income. In the face of this bad news, to find the support they need, people are turning to a model of social service programming that dates back hundreds of years: mutual aid funds.

Two recent reports have highlighted this movement. Elizabeth Lawrence, writing for NPR, describes the mutual aid funds and programs that are springing up in New York City, ones that are neighborhood-based and offer support to people who are elderly, ill, or out of work. Meanwhile, Sarah Cascone reporting for Artnet News, describes how museum workers have rallied to create mutual aid funds to help colleagues who have lost their jobs.

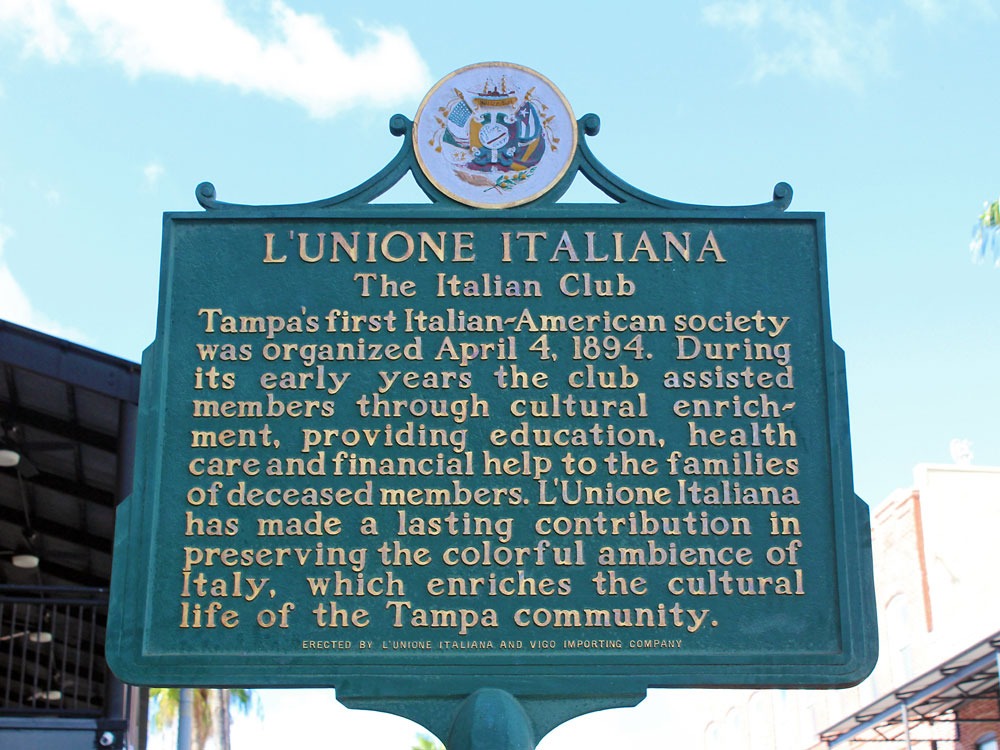

Mutual aid societies or funds are nothing new in America. They date to the 1700s, when they were formed by groups that did not have access to mainstream resources. The goal was to come together and deliver financial or social service benefits to their membership. For example, the Free African Society was created in 1787 to provide aid to newly freed Black folks. Later, immigrant groups coming to America would form mutual aid societies like the Società di Mutuo Soccorso for Italians and the Sociedades Mutualistas created to support Mexican immigrants.

Although many of the benefits mutual aid societies used to offer are now embedded in insurance companies and social service agencies, the economic downturn has led once again to many people being unable to access what they need. So, as they did hundreds of years ago, people are coming together and finding ways to share resources and money with their neighbors to help them through the hard times.

For example, Bed-Stuy Strong was created to help people in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn. One woman who contracted COVID-19 in March of this year had to quarantine herself from the rest of her family; Bed-Stuy Strong helped by bringing cooked food to her apartment. In her recovery, she is now helping deliver food to others in her neighborhood.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

An ancillary benefit of these neighborhood-based mutual aid societies Lawrence describes is that people now feel more connected to their community. The volunteers meet people they would otherwise never talk to. It’s giving rise to a feeling of strength and solidarity in neighborhoods that are experiencing gentrification.

The model Cascone reports on is based not in a neighborhood, but in a professional field. In New York City alone, more than 15,000 people who worked at arts nonprofits are now out of work. Their colleagues are gathering together, creating mutual aid funds, and generating support. In some cases, employees at a specific institution are raising funds to help their former colleagues who are now out of work, such as the Tenement Museum Union in New York. The newly unionized workers suddenly found that more than 70 people were being let go as the museum shut down during quarantining. Some of the remaining workers immediately created the mutual aid fund and started a GoFundMe project. Within 24 hours, they had raised more than $25,000.

It seems they are not alone. There are also projects like the Black Resilience Fund in Portland to provide immediate financial relief to Black Portlanders. Launched on June 1, 2020, the fund has generated more than $1 million. Then, there is the COVID-19 Mutual Aid Fund for LGBTQI + BIPOC folks in California. This fund targets LGBTQ+ people of color who are often self-employed and are often living with disabilities and/or compromised immune systems. The fund has raised $253,000 since its inception in March of this year.

Lawrence points to a website called Mutual Aid Hub, which reports that as many as 59 mutual aid groups are now active in New York City. Cascone notes that funds are popping up for former workers at specific museums and also for the whole industry in the Museum Workers Relief Fund.

Sometimes, you gotta love people. When the chips are down, they turn to each other and find a way to help out.—Rob Meiksins