September 10, 2018; San Francisco Chronicle

A million-dollar lawsuit is underway between the nonprofit Alcor Life Extension Foundation, based in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Kurt Pilgeram, the son of a deceased scientist.

Pilgeram, reports Annie Vainshtein in the San Francisco Chronicle, “filed the suit after he received a package containing the cremated remains of his father, Laurence Pilgeram’s body, save for his head. Pilgeram claims the firm had been mandated to preserve all of his father’s remains.”

Alcor, Vainshtein explains, “charges $200,000 to cryopreserve the entire body and $80,000 just for the head.” According to Olivia Messer of the Daily Beast, Pilgeram “claims that the cremation of the rest of his father’s body was a breach of contract and diminished the hopes” of him being brought back to life. Alcor, in its defense, indicates that the reason the body was not preserved was because the body was “medically unable to be preserved” due to too much time passing between the time of death and when Alcor received the body.

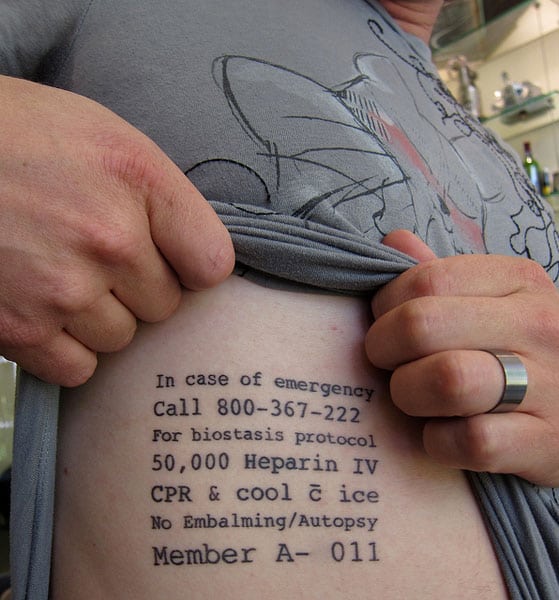

Cryonics uses vats of liquid nitrogen, stored at ultra-low temperatures of roughly -320 °F (-195.5 °C), to preserve humans and animals. “If the timing is right,” Vainshtein explains, “the cooling should suspend the physical decay of the brain, organs, and tissue—making future resuscitation theoretically viable.”

As Cassidy Ward explains for SyFy Wire:

Cryonics hopes to take advantage of the brief time between legal death and the destruction of the inherent biological information contained in the body and the mind brought on by decay. By lowering the temperature of the body (or in some cases, just the head) we can, with current technologies, effectively stop biological time. This puts a stopgap in decay, preserving the information that makes a person who they are, in hopes that future advances in medical technology will restore the deceased to full health.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The plaintiff’s father, Laurence Pilgeram, died at the age of 90 in 2015. He received his doctorate in Biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley in 1953. He specialized in the study of aging and would regularly speak at cryonics conferences during his lifetime. In 1991, he became a “member” of Alcor—that is, he signed a contract with Alcor in which he paid to have his body cryonically preserved upon his death.

As of the end of last month, Alcor, notes Vainshtein, had 161 “patients,” in cryonics lingo. Baseball great Ted Williams, who died in 2002, is probably the nonprofit’s most famous patient—that is, a person who has died and been placed into a deep freeze. “Members”—of which Alcor now has over 1,200—refers to people who have signed contracts to have their brains or their entire bodies undergo cryopreservation upon death.

As for the lawsuit, Vainshtein notes that, “This isn’t the first scandal to strike Alcor. Since its founding in 1972, Alcor has come under fire several times, including for its alleged mishandling of baseball icon Ted Williams’ head.”

Of course, whether any of those 161 patients could ever regain consciousness remains doubtful. Then, there are all of those science-fictional questions about what it would mean if you actually could resuscitate a person who has been in a deep freeze for decades (or longer). Dr. James Bedford, a California psychology professor, was the first to undergo the process. If Bedford, who died in 1967, were one day revived, how well would he do in a society very different than the one he knew?

Odd legal issues could also arise. For instance, many nonprofits receive donations through bequests. But if you plan to come back to life one day, you may want to set up a revival trust so you have a bank account when you regain consciousness. A revival trust, apparently, is “an estate planning niche for clients having their bodies frozen until medical science can restore them to good health,” according to attorney James Dedon. Dedon’s article includes useful advice, such as, “If real property is included in the revival trust, such as a beach house or mountain retreat, consider allowing descendants limited use.” Dedon, however, does not indicate whether the trust might also permit limited use by a beneficiary nonprofit.

According to Vainshtein, a trial on the merits of Pilgeram’s lawsuit is expected to take place in January.—Steve Dubb