September 25, 2019; Hyperallergic

The building of art spaces that are representative of Indigenous communities extends far beyond the gallery walls. An exhibition at Seattle’s King Street Station, called yəhaw̓, was the culminating event of a year-long project that actively engaged with the process of creating and experiencing diverse Indigenous art. The show was co-curated by Tracy Rector (Choctaw/Seminole), Asia Tail (Cherokee), and Satpreet Kahlo.

The name of the exhibit and the year-long project it represents is intertwined with its process. According to its website, “the title of the show is drawn from the Coast Salish story of people from many tribes uniting around a common cause and lifting the sky together. In the spirit of that story, we [the curators] used a decolonized curatorial process, inviting all Indigenous individuals living in the region to participate.”

When the King Street Station was being redeveloped, yəhaw̓’s curators spoke directly with Seattle’s Office of Arts and Culture. With the space secured, they began a year-long project of Native-to-Native mentorship and artist residencies. The groundwork laid before the exhibit culminated in an inclusive and representative display of Indigenous art of all forms this summer.

The exhibit included a notably large number of artists, with 200 featured exhibitors. Of those, over half (130) identified as women and 30 identified as Two Spirit or queer. Young people were also actively welcomed into the artistic process.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

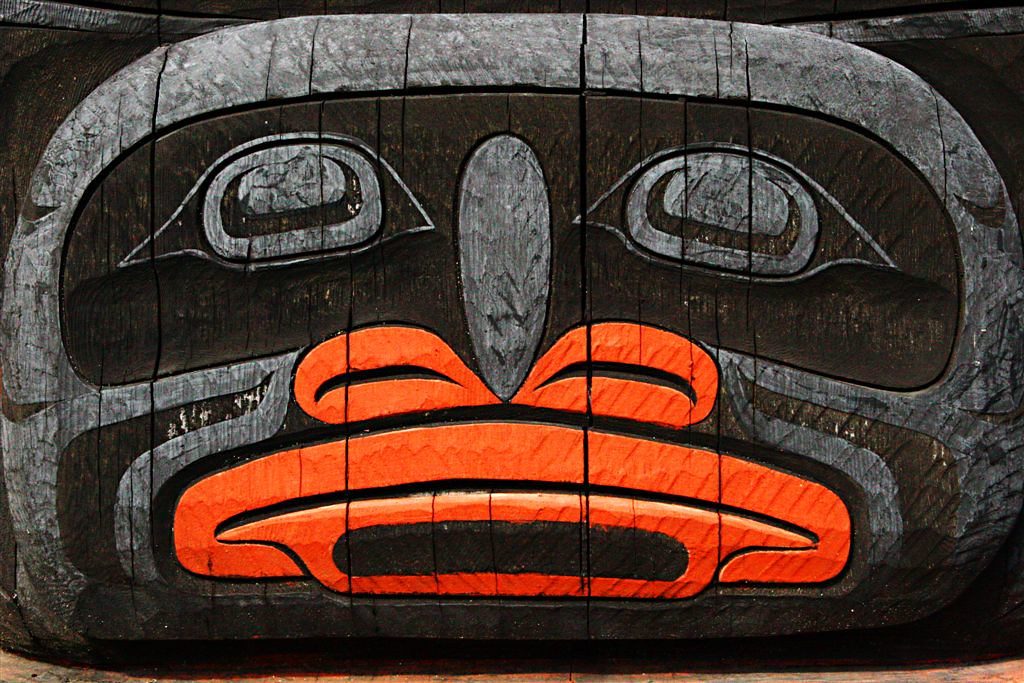

Designed by indigenous people around indigenous narratives and world views, the exhibit seeks to decolonize traditional art narratives and focuses on uncovering the complexity of meaning. Artwork isn’t grouped by tribe affiliation, region, or time period, as is common in museums; instead, curator Asia Tail grouped works she found “visually resonant and conversational,” emphasizing experience and indigenous understanding over standard Western categorization.

In conjunction with the exhibit, the project included “satellite installations, performances, workshops and trainings, artists-in-residence, art markets, a publication, and partner events at more than 25 sites across Coast Salish territories and beyond.”

At a yəhaw̓ Indigenous Teen Art Show associated with the exhibit, teens were accepted to present their art without restrictions, giving them space to express and explore their identities.

“It’s extremely difficult to be indigenous just in general,” Namaka Auwae-Dekker, a teen who shared her poetry during the event shared with the Seattle Globalist. “Having to constantly justify your people and proving that you are still here…indigenous people are often talked about in past tense, or we’re not acknowledged, so it’s very challenging.”

So, what does it take for an art gallery project to actively participate in the development of Indigenous art spaces? In the case of the yəhaw̓ project, it requires not engaging with a colonial voice, but standing defiantly separate from it.—Julie Euber