At this point, Black people must be the most well-researched, well-studied, and well-documented people on Earth. Yet on balance, very little changes regarding their socioeconomic condition. Indeed, as Robert D. Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett document in their recent book The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again, African Americans are worse off today than in 1968 across many socioeconomic measures of well-being. We write report after report documenting the levels of racial, economic, and social inequalities. We march, vote, and protest to incremental effect. But even in the wake of the heinous police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and a too-long list of others, we’ve seen no substantial change.

Even with the concerted, multifaceted national and international civil uprising over the last ten months, Black men and women continue to be gunned down in the streets of America.

Even in the face of a pandemic where the data show Black people are dying from COVID at unprecedented rates, little has changed when it comes to how Black people are treated in our systems.

The problems persist and, in fact, have become deeper and more embedded into the fabric of our community.

In the first two-thirds of the 20th century, Putnam and Garrett observe, “Gains on the part of Black Americans…were due almost entirely to their fleeing the South by the millions during the Great Migration.” The ability of Black Americans to move to industrial jobs enabled many to escape poverty, even in the face of unceasing white resistance to Black gains. But in the past 50 years, they add, white backlash to civil rights laws provoked a “shift away from shared responsibilities” that has led to today’s extreme economic inequality and has “slowed, stopped, and even reversed” movement toward racial equity.

At one time, I believed in the rational argument that if we compiled enough data on African Americans’ social and economic plight, we could win the day. If we could harness enough data, white people would wake up and realize that their ill-gotten privileges created a rigged system. Then, they would relent and change the system to help equalize the playing field in America.

Years and many reports later, I have come to a different conclusion.

The current dilemma facing Black people isn’t about logic or making the best argument. This is not something to be solved using a purely rational approach. It is not just about the disparity data. People of good will have worked for many years to address some of these “wicked” problems of economic and social justice for Black people in America from just that standpoint.

The current dilemma is about shaping our future, our images of what it means to be Black in America. It’s about creating enough social cohesion and building a movement to amass the power necessary to change the system. We need to frame a positive image and a new Black ethos to change our current circumstances.

This is about the complex adaptive systems of human relationships—of belonging and identity.

Putnam and Garrett write that “one lesson of the complex history of race in twentieth-century America is perhaps simply this: ‘We’ can be defined in more inclusive and or exclusive terms, and that inclusiveness can gradually change over time. But a selfish, fragmented ‘I’ society is not a favorable environment for achieving racial equality.”

We need to develop a shared, strength-based narrative and identity so that everyone can see themselves in the picture.

Our Stories Shape Us: A Visit to Standing Rock Nation

My own personal story of discovering my identity and redefining my narratives illustrates how we can transform a broad deficit narrative into a strength-based framework for individual and group deliverance.

A few years back, I had the opportunity to visit the Standing Rock Nation in South Dakota. Little did I know it at the time, but this visit would profoundly impact my life and lead me on a remarkable journey that redefined my personal and group identity.

Standing in the Council chambers, then Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault II introduced himself by reciting his lineage going back seven generations. He then asked each of us to introduce ourselves. I remember, as my turn came, mounting anxiety as I thought about what to say. I did not share the same pride in my family lineage. All I knew about my family heritage was that they were held in bondage and enslaved.

I listened intently as my African American colleague stated that she was the daughter of sharecroppers from Mississippi. While technically correct, her lineage went back to slavery, just like mine. I have noticed many African Americans gloss over the reality that we were enslaved property traded on the market like other commodities. It is a shameful part of US history.

I, too, never publicly acknowledged my ancestors as enslaved people. However, this time was different. When it came time for my introduction, I said, “I am Gary Cunningham. I am an African American, a descendant of enslaved people. My people migrated to Minnesota from Oklahoma and Mississippi to escape Jim Crow laws, the Klan, and sharecropping.” The tribal elders nodded with understanding.

For me, time stood still in that council chamber. It was an awkward moment. This uncomfortable yet pivotal moment propelled me on a journey to learn about my enslaved ancestors. It ignited a determination to know my history and heritage, to shed the intergenerational and collective shame I carried.

Our perception of our self-identities shapes our reality.

On Resentment, Trauma, and Pain

Many forces shape our individual and group identities. An example is the ways in which our ethnic or racial ancestry and personal history tell important stories about how we perceive ourselves and how others perceive us in society.

Black people live, understandably, in a constant state of anxiety and insecurity created by external actors in hostile environments. Slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, discrimination, redlining, welfare policies, police violence, and race-based economic inequalities have undermined Black folks’ basic trust systems. Meanwhile, white people continue to damage their humanity by perpetuating racist systems that violate their own purported social and economic principles.

When individuals or social groups live in a constant state of insecurity created by external actors or hostile environments, basic trust systems become distorted, which in turn distorts their sense of safety. We also know that individuals in hostile situations will often remain in those situations. Some people and groups are attached to their routines, even to their detriment.

In Merge Left, Ian Haney López and his team conducted thousands of interviews and surveys with people of all races on the framing of racial justice. He found that “whites filter narratives about racism against people of color by asking what it means for them as white people.” Lopez also found that many African Americans were skeptical that anything could change to address racism in the US. As one focus group member stated, “You can have rallies and, you know, just do anything to try to make a change for the better, and whoever the powers may be, they’re going to do what they want to do, what they are compelled to do anyway.” Underlying these statements is a lack of essential trust and imagination needed to resolve the dilemma of racism in America.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Groups lock themselves into conflicts where no one wins. It is difficult to change routines, even when they serve as impediments to progress. It can feel safer to hold on to resentment, trauma, and pain.

A Revelation

I vividly remember my maternal grandmother sitting in her living room on the vinyl-covered white couch. Seven grandchildren gathered around her feet as she told us stories about growing up in Oklahoma. I loved to listen to her; she was a great storyteller. It was with my grandmother’s stories that my genealogy quest began.

With my grandmother’s stories to guide me, I traced my maternal family from Oklahoma to Alabama, to my fourth great-grandparents, Jesse and Rose Franklin. At the time, I did not understand how, as slaves, Jesse and Rose had moved from Alabama to Oklahoma in the 1830s. I posted what I knew about Jesse and Rose on various genealogical bulletin boards.

Several days later, a woman emailed me a beautiful note acknowledging that her family had enslaved my ancestors. She sincerely apologized. She went on to explain that she and her family are citizens of the Creek Nation. As a part of the Indian Removal Act, over 100,000 citizens and over 4,000 enslaved people of Five Civilized Tribes were forced to march the Trail of Tears from Alabama to Oklahoma. Over 4,000 people died on the Trail of Tears, including my ancestors.

I was shocked. I had no idea American Indians had enslaved my people.

The Creek Tribal member’s apology to me for my people’s enslavement was like a healing balm. I reexamined my narrative and lifted the shame from my shoulders.

Developing a New, Pro-Black Narrative

Every day, African Americans are bombarded with negative messages about who we are. The depressing statistics of education, health, household income, wealth, and homeownership produced by well-meaning think tanks are reported constantly. African Americans become numb to the drumbeat that Black outcomes are worse than every other group in America, with the possible exception of American Indians.

Unwittingly, many of us reinforce long-held stereotypes. These negative stereotypes impact our psyches. Repeated negative images, reports, and stories create reinforcing feedback loops that strengthen and replicate poor outcomes.

Black people are under continuous threat of being stereotyped. Social psychologists call this “stereotype threat,” meaning a situation in which people are, or feel themselves to be, at risk of conforming to stereotypes about their social group. The stereotype threat theory states that if negative stereotypes are presented to a group, such as African Americans, they are likely to become anxious, which may hinder their performance or their ability to operate at their full potential. With stereotype threat, the individual does not need to subscribe to the stereotype for it to be activated.

Social science research shows that stereotype threats impact academic performance, contributing to long-standing racial gaps. African Americans continue inadvertently to reinforce stereotype threats in both in-group and out-group interactions.

Cross-cultural psychiatrist Dr. Welansa Asrat in an article in The Root states that “Society’s anti-Black bias can be effectively countered with a pro-Black bias. In psychiatry, we talk about risk factors for particular disorders. However, there are also protective factors. Exposure to anti-Black bias is a risk for internalized racism and low self-esteem. However, a pro-Black identity can protect against the risk.”

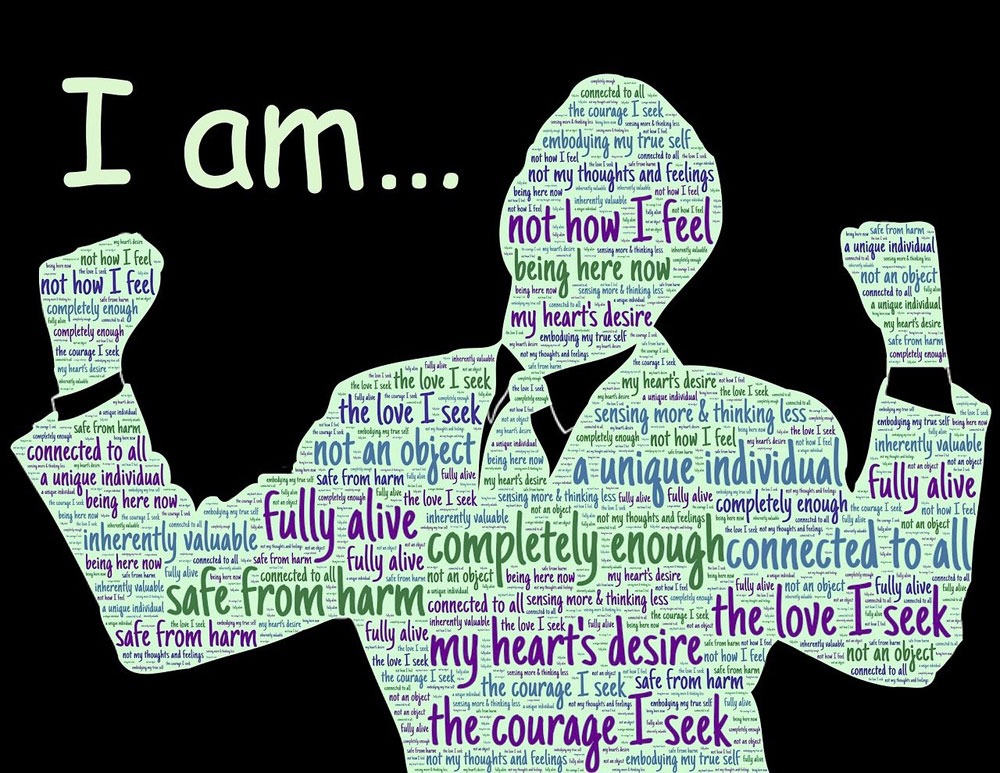

To counter stereotype threat, social psychologists suggest creating a “stereotype boost.” The boost includes self-affirmation, building a positive image and self-esteem, and clarifying why distractions and anxiety do not implicate or invalidate oneself. To change the conditions for African American people, we need to create a stereotype boost by building a strength-based narrative.

The late Professor Emeritus Dr. Joseph White, the father of Black psychology, began to frame a new narrative based on stereotype boost when he formulated the Seven Psychological Strengths of African Americans. These psychological strengths are improvisation, resilience, connectedness to others, spirituality, emotional vitality, gallows humor, and a healthy suspicion of you-know-who.

We need to create this stereotype boost on a massive scale. Positive proactive images, reports, and analyses need to reflect the fantastic contributions African Americans have made to this country. Over the years, Black Pride has been lifted up in our history, heritage, and culture. But too many of these approaches have gone by the wayside.

By building positive reinforcing stereotypes, we will create greater social cohesion within the Black community. Greater cohesion is necessary if we’re going to develop a winning strategy to address the wicked inequalities that persist.

Every public and private institution should have a conscious positive pro-Black message. Instead of simply stating that an organization is antiracist, institutions should frame antiracism through positive affirmations about Black people.

We must tell a different story about who we are, one that comes from a place of stereotype lift rather than stereotype threat. We must develop a new, pro-Black narrative.

Starting from a Place of Strength

As I dug deeper into my genealogical past, I uncovered a book entitled African Creeks by historian Gary Zellar. Dr. Zellar documents the plight of enslaved African people who were members of the Creek Nation. For example, my fourth great-grandfather, Jesse Franklin, fought in the Civil War as a Union cavalry officer. Franklin was one of the West’s famous Buffalo Soldiers. After the war, as a Freedman and Creek citizen, he served as a representative in the Creek House of Warriors (1867–1875). He was the first African American tribal citizen to serve as a Supreme Court Justice for the Creek Nation.

Another surprise was finding out that my second great-grandfather, Jim Taylor, was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. Taylor fought and won a protracted court case for the right to be a full citizen of the Cherokee Nation. My family, of both the Creek and the Cherokee lineages, received land allotments in Oklahoma. Some of this land remains in our family’s hands to this day. Where many African Americans never got the 40 acres and a mule, my family received theirs.

I am now a registered member of the Muskogee Creek Indian Freedmen Band. I am also applying to become a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. Under the 1866 treaty, any Freedman ancestor is a full citizen of the Cherokee and Creek Nations. However, as I write this, the Muskogee Creek Indian Freedmen Band is still fighting for our rights to be full members of the Creek Nation.

I never knew there were so many heroes in my ancestry. It has been a remarkable journey. Now I tell my grandchildren about the heroic journey of their ancestors—including my own quest, a journey which began with an awkward moment at Standing Rock Nation, and, like a version of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, culminated in personal transformation and a new and stronger identity.

The stories we tell ourselves create myths that can transform our reality. To change our trajectory, Black people must start from a place of strength.