“It’s not going to help me—I’m through mining,” retired West Virginia coal miner James Bounds told the AP. “But we don’t want these young kids breathing like we do.”

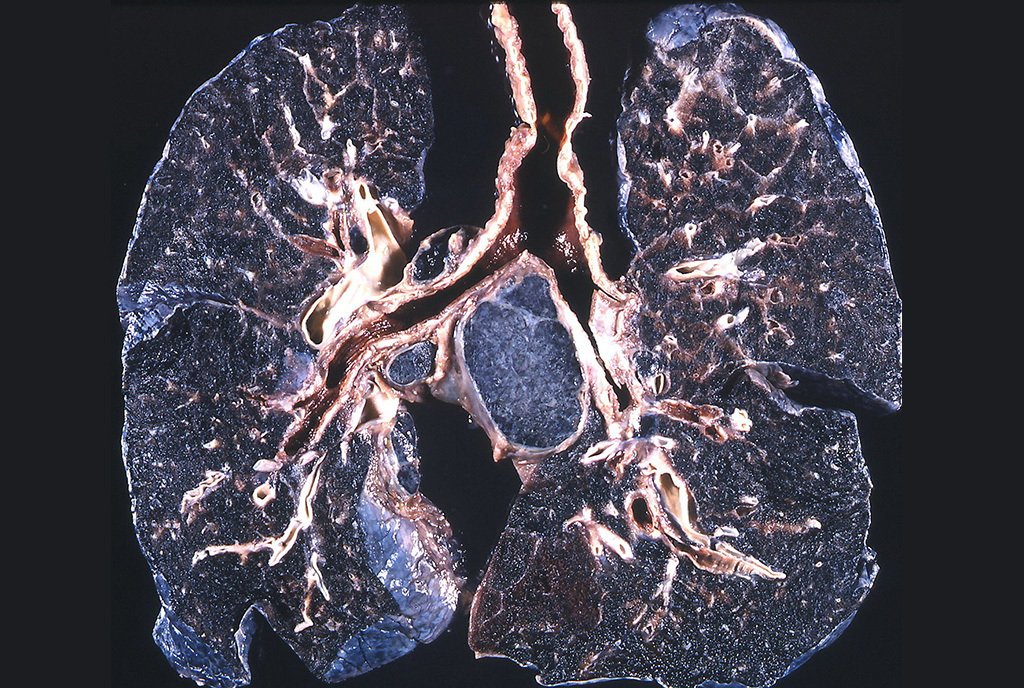

Bounds is 75 and uses supplemental oxygen to breathe. He was 37 when he was first diagnosed with pneumoconiosis, commonly known as black lung. Pneumoconiosis scars lung tissue, which in turn impairs breathing. Early symptoms of black lung are coughing, including coughing up black mucus, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. No treatment can reverse the damage inflicted by inhaling coal dust. It’s a devastating illness that can be fatal or lead to serious complications such as lung cancer and heart failure.

And it’s making a comeback.

What’s behind the return of black lung, why it is striking miners at younger ages than ever before, and what are the policy responses to curb the disease’s spread? This time more than coal is to blame for the deadly illness.

Digging Down Deeper

Black lung had been in decline since the 1970s, hitting a record low in the 1990s as a result of safety regulations. The 1969 Coal Act, limiting the amount of coal dust to which miners could be exposed, is attributed to the decline.

He said breathing felt like “a clamp around his chest.”But in 2005, cases of black lung began to rise again sharply. As the University of Illinois wrote in 2022, “Subsequent investigations have reported that black lung cases have tripled and that tenured miners in central Appalachia, the epicenter of the disease, have experienced a tenfold increase in severe black lung disease.”

In 2018, an investigation by NPR and Frontline “found evidence of an outbreak of a severe form of black lung disease called progressive massive fibrosis—in numbers far more extensive than federal monitors had reported.” Dust collection data, information that had been acquired over decades, showed that miners had been exposed to toxic dust “thousands of times.”

That toxic dust is silica, which is created when cutting into sandstone. Sharp particles are generated when the stone is cut, and the particles are embedded in the lungs when breathed in.

The Wall Street Journal reported that experts linked the rise in black lung cases to these “higher levels of toxic silica dust as miners grind up more rock to retrieve coal from thinner seams—sometimes no more than 30 inches high.” They interviewed one former miner, Kevin Weikle, whose career ended at age 34 due to progressive massive fibrosis and diminished lung capacity. Weikle described cutting into sandstone for one whole shift. He said breathing felt like “a clamp around his chest.”

Why are miners being exposed to silica in the first place? As Kirsten Almberg, a research assistant professor of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago, wrote in 2022: “Much of the ‘easy’, or thin-seamed, coal has been mined out.” And as Public Health Watch reported a year later, “After more than two centuries of mining coal in Central Appalachia, there are few large, thick coal seams left in the region. Now, workers in Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia grind through more rock filled with quartz to reach the coal.”

The odds of a miner dying of a respiratory disease are four times higher now than a century ago.

As miners dig down deeper to reach less readily available coal, grinding into those rocks to mine coal from even thinner seams, the silica dust—which is 20 times more toxic than coal dust—is generated. High levels of silica have been increasingly found in mines since 1986.

More miners than ever before are being exposed to the hazard, with problems showing up much sooner. Miners are now being diagnosed with black lung in their 30s and having severe problems by their 40s. Some, like Weikle, must retire decades early due to declining health. One West Virginia physician interviewed by the AP described the cases of black lung in his area as “skyrocketing.”

According to the Wall Street Journal, the odds of a miner dying of a respiratory disease are four times higher now than a century ago. Miners diagnosed with black lung are also dying earlier, likely due to the increased severity of the disease.

Halving Silica Dust Exposure

How is the industry responding to black lung’s resurgence?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This year, the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration proposed a rule halving the amount of silica dust miners can be exposed to during their shifts. Currently, miners on an eight-hour shift can be exposed to 100 micrograms of silica dust per cubic meter, which as journalist and activist Kim Kelly pointed out in a previous interview with NPQ, is “double the legal amount of every other occupational health standard.” The new rule would make it 50.

While halving silica exposure seems promising, Kelly reflected on the new limits: “This new rule is just a start…[50 micrograms] still sounds like too much, but I suppose it’s baby steps when it comes to federal regulations.”

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) actually recommended the lower level of exposure back in 1974. But as NPR and Frontline reported in 2018, their joint investigation uncovered “decades of regulatory inaction.”

However, preventing black lung is completely dependent on regulatory intervention and political will. As Kelly stated, “No one needs to get this disease. It’s completely preventable, at least according to the various experts I spoke to, including veteran coal miners, mine safety experts, and health experts.” Professor Almberg echoed this point, “Coal mine dust lung disease has one cause—over-exposure to coal mine dust. We know the causes, we know the public health implications, so the question becomes, why does this persist?”

With the introduction of the new rule, political momentum seems to be shifting. Industry trade organizations, including the National Mining Association, which represents mine operators, now support it. So do many politicians representing Appalachia, including Democratic Senators Joe Manchin (WV), Sherrod Brown (OH), Bob Casey and John Fetterman (PA), and Mark Warner and Tim Kaine (VA). A period of accepting public comments on the rule has now closed, and hearings on the rule will be conducted in Arlington, VA; Beckley, WV; and Denver, CO.

During the public comment phase, miners gave emotional testimony to regulators, according to the AP; retired miner Terry Lilly implored that the new rule “will mean nothing if there aren’t strict enforcement mechanisms in place to ensure companies comply.”

As it stands currently, the rule will be enforced by sampling dust to make sure the silica is within limits. And as Public Health Watch reports, its “effectiveness will depend on mining companies sampling their own mines and responding accurately and honestly. There’s a long history of coal mining companies, when left to their own devices, cheating dust safety standards.”

“Cheating the samples is what we need to stop. If we can stop this, we can save some lives,” said Lilly, who after 30 years in mining only has 40 percent lung capacity.

Lilly’s observation speaks to the tensions surrounding the rule’s implementation. Coal companies themselves have been slow to respond publicly, and it’s not yet clear how they will be held accountable to the new requirements. Indeed, many feel the rule does not go far enough to meaningfully protect miners. For example, the rule calls for companies to “replace existing outdated requirements for respiratory protection with a standard that reflects the latest advances in respiratory protection technologies.” But according to the AP, “the mine workers’ union and others…say respirators are ineffective while performing heavy labor in hot, confined spaces common in mines.”

“Nobody should be dying because of a job they have.”

The Timing Is Right

While some friction remains around silica dust monitoring and improved safety standards outlined in the rule, safety officials and others are generally united around new systems to support miners, including mandatory screening for black lung. Early diagnosis is critically important, as miners with black lung have options. As the Wall Street Journal reports, “Under federal law they can transfer to a job with less dust exposure, without any loss in pay, if they have been diagnosed with black lung, even if they are still symptom-free.”

What’s prompted this rule, first proposed decades ago, to be finally—potentially— moving forward? It may be the steep rise in cases, the earlier age at which miners are being impacted, or the new and sharper attention focused on the issue. Assistant Secretary for the Mine Safety and Health Administration, Christopher Williamson, said in USA Today, “The consensus is that miners should have the same protection as other workers with silica dust,” such as construction workers, already protected under 2016-era Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards.

“The timing is right to move forward on it. We know that miners need greater levels of protection,” Williamson said.

And as United Mine Workers of America President Cecil Roberts told the AP, “Nobody should be dying because of a job they have.”