March 23, 2016; Washington Post and Education Week

If we don’t fix crumbling walls and leaking roofs, or make sure the water is safe to drink, will it really matter if we have the best teachers with the best curricula for our children? Recent stories about the conditions of schools in Detroit and other major cities illustrate questions that should be front and center for those leading our public schools. A new study, State of Our Schools: America’s K–12 Facilities, tells us that we are not going to like how they have been ensuring we will like the answers to those questions.

Rachel Gutter, coauthor of the report, told the Washington Post that the study shows consistent and persistent underinvestment in our nation’s schools. “Communities want to resolve these issues, but in many cases the funds simply aren’t there.” The study, a joint effort of the 21st Century School Fund, the National Council on School Facilities, and the U.S. Green Building Council, sought to take the first comprehensive look at school buildings since a study completed by the GAO in 1995. Its findings were based a comparison of the annual rate of spending over the three last years and the levels projected needed to properly maintain existing facilities, complete necessary upgrades, and develop new facilities. It was not comforting to find that they estimate we are underfunding the capital needs of our schools by $46 billion per year!

The Nation Underinvests in Public School Facilities

|

K–12 FACILITIES |

Historic Spending | Modern Standards | Projected Annual Gap | |

| Maintenance & Ops | $50bn

|

$58bn | $8bn | |

| Capital Construction |

$49bn |

$77bn | $28bn | |

| New Facilities | $10bn | $10bn | ||

| TOTAL | $99bn | $145bn | $46bn |

Beyond putting a dollar figure on the funds that will need to be found, the study tells us that the impact is not shared equitably across the nation. Districts serving low-income populations have the greatest gap between what is needed and what they are actually spending on the facilities: “A study of more than 146,559 school facilities improvement projects from 1995 to 2004 found that the projects in schools located in high-wealth zip code areas had more than three times more capital investment than the schools in the lowest-wealth zip code areas.” This disparity between rich and poor is made greater when the cost of the borrowing is added to the cost equation. Districts in high wealth communities can borrow at lower rates, while those in low wealth districts pay higher rates if they can borrow funds at all.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The impact of this funding shortfall hits directly on the effectiveness of the overall educational program of our schools:

Research shows that high-quality facilities help improve student achievement, reduce truancy and suspensions, improve staff satisfaction and retention, and raise property values. They also are integral to ensuring equity in educational offerings and opportunities for students. Even so, no comprehensive information about school building conditions or funding is available at the national level, nor in the majority of states, despite the importance of this infrastructure and the enormous investments made by U.S. taxpayers.

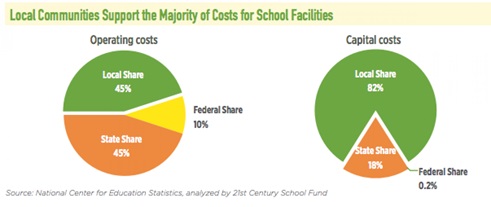

Responsibility for this situation heavily rests on political decisions that placed responsibility for paying for facility costs primarily on local school districts rather than on the state or the federal governments.

Because the large majority of capital construction is funded by local taxpayers, the ability of school districts to pay for major renewals or new construction is tied to the wealth of their community, perpetuating inequity in school facility conditions. Additionally, while funding to support facilities M&O combines local, state, and federal sources, M&O competes with other essential aspects of school district operations, such as salaries and instructional equipment, which also need to be paid for through the same general operating budget. Therefore, school districts, especially those low- wealth districts that have not been able to spend needed capital construction funds to make major repairs to their buildings, are put in a position where they must stretch their general operating funds to try to make up the difference.

Mary Filardo, the executive director of the 21st Century School Fund put the described the challenge posed by the study’s findings in an interview with Education Week.

We have to be able to plan; we have to set priorities to make sure we are doing what’s most important first. And what we know is that you don’t get equity without planning. The people who have access and power will get things for their communities that they need, and those without access to power will not. We do need new public dollars; there aren’t enough public dollars out there. The pie itself needs to be bigger.

The report adds another layer to the challenge of making public education systems equitable and responsive—and not to only those with the most resources. A growing body of knowledge is telling us that to improve our educational systems, we need to do more than break teachers’ unions, narrow the curriculum, and test our students. Will those who have not been listening be willing to listen now?—Martin Levine