NPQ has tried to cover some of the misconceptions we feel the media and the public have about Muslims and Islam. When we heard about the backlash over an Islamic calligraphy assignment at a rural Virginia school that led to the school district closing all the schools in the county, we felt we should pause to see the reactions and coverage of the story. What we found was the distinct absence of Muslim voices and representative nonprofit groups in the coverage.

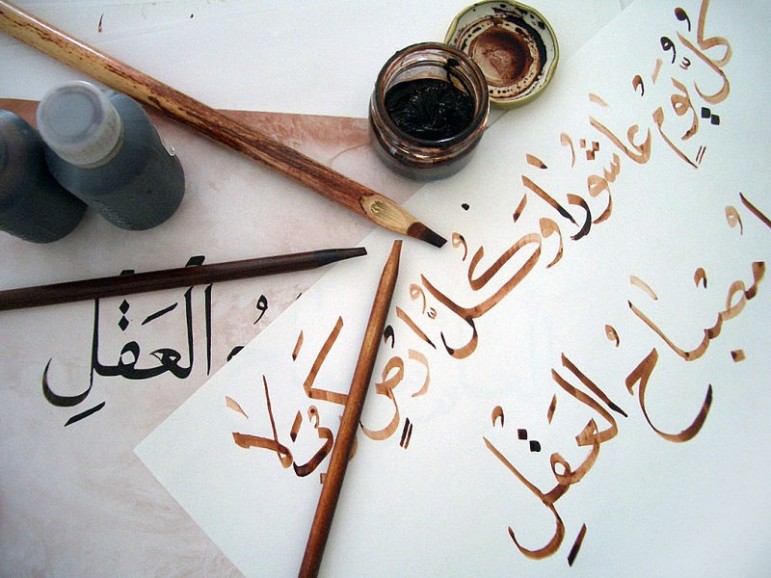

If you have not heard, at Riverheads High School in Staunton, Virginia, Cheryl LaPorte, a teacher of the World Religions class, had her students copy Islamic calligraphy as part of an assignment. The assignment, taken from a workbook, said, “Here is the shahada, the Islamic statement of faith, written in Arabic. In the space below, try copying it by hand. This should give you an idea of the artistic complexity of calligraphy.” While the calligraphy was not translated for the students, it reads, “There is no god but Allah, and Mohammed is the messenger of Allah,” the first of five pillars of Islam.

The purpose of the assignment was to educate her students about Islam, a faith with billions of followers worldwide, and the class as a whole was meant to expose students to religions outside their own. The actual impact of the assignment was dozens of vitriolic emails and calls from angry parents saying the school and teacher were indoctrinating their children by teaching them Islam.

We won’t delve into the claim of indoctrination here; we wager if the students were made to copy a different religious statement from a religion more dominant in the U.S., there would not be the same level of controversy. Instead, we will provide some thoughts that many Muslims likely had when reading this story, which appear to have been completely overlooked or intentionally omitted by the media.

To begin with, some Muslims would likely object to rewriting the “shahada” as a school assignment, particularly by students who do not follow the faith. The shahada is an incredibly sacred, foundational statement in Islam, and it is supposed to be the last and final declaration a Muslim makes before he or she dies. Writing the words down in Arabic confers the sanctity of the words to the paper. Never mind the parents of the children in the class—writing the shahada and mixing religion in school in this way is likely why some Muslims and others are offended by the assignment.

As a Muslim parent raising a secular humanist, I would protest my son writing the shahada in school https://t.co/k7SaQnCJq9 #MuslimReform

— Asra Q. Nomani (@AsraNomani) December 18, 2015

okay perhaps choosing the shahada to “try your hand at writing in arabic” isnt the most appropriate lesson, belittling the statement itself

— peacock bandit (@Xtreme_JWhitt) December 21, 2015

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

@iyad_elbaghdadi @HindMakki As a teacher it was stupid to copy shehada in public school. I’m Muslim, plenty of diff writing samples to use

— Leanne Scorzoni (@LeanneScorzoni) December 18, 2015

No public schools assign Hebrew calligraphy to students.Why Arabic? Does this teacher know what the “shahada” is? https://t.co/M0JkAqPexh — Barbara Kay (@BarbaraRKay) December 20, 2015

It’s important to realize that the school district rallied around the teacher and supported her decision to utilize the assignment in class. “Both the Virginia Department of Education and Superintendent Eric Bond have reviewed the material and found it both in line with state standards, as well as not in violation of students’ rights,” according to the News Leader. It’s concerning that neither the school district, the state board of education nor the teacher considered the impact of using a religious statement like the shahada in class. Did they know the importance of the phrase within the religion? Do they have any knowledge of Islamic calligraphy before presenting a lesson on it? Ironically, it shows a level of ignorance of the very religion the teacher is attempting to educate her students about.

As an undergraduate, I wrote my honors thesis on Islamic calligraphy. Some styles of calligraphy in Islam are inherently religious. The extravagance and the elegance of the writing are meant to relay the importance of the religious prayers and sayings. There are, however, other styles that are used specifically for nonreligious purposes, such as poetry or prose, that look very similar to the stylized writing as seen in the assignment. If the teacher or the school had done their research, as befits their duty as educators, any of these other styles could have served the same purpose in the assignment without causing offense.

A poorly researched article in the Atlantic proposed the use of another religious phrase instead. “Why not bismillah al-rahman al-rahim (in the name of God, the most gracious, the most merciful), a far less charged phrase?” This phrase is also one of the staple religious prayers in Islam. Nearly all chapters of the Qu’ran begin with this religious phrase. It’s not any less charged, religious, or important than the shahada. But it’s just as offensive to a Muslim for a school to nonchalantly use the statement as calligraphy practice.

It’s very easy to lose the message of this incident amid the handful of parents crying indoctrination. However, this incident in rural Virginia and the media’s coverage of it only showcases what we have seen repeatedly in society; a breakdown in understanding Islam and Muslim culture. Ideally, parents should be concerned not that students are learning about Islam or its history in school, but over the quality of the education they are receiving.

These incidents also give some of us at NPQ an opportunity to reflect on the inherent flaws in reporting and journalism. No one expects high school teachers or national reporters to have the same level of understanding of Islam as a practicing Muslim or a dedicated scholar, but are they even trying?—Shafaq Hasan