May 18, 2016; National Public Radio, “nprED” and the Los Angeles Times

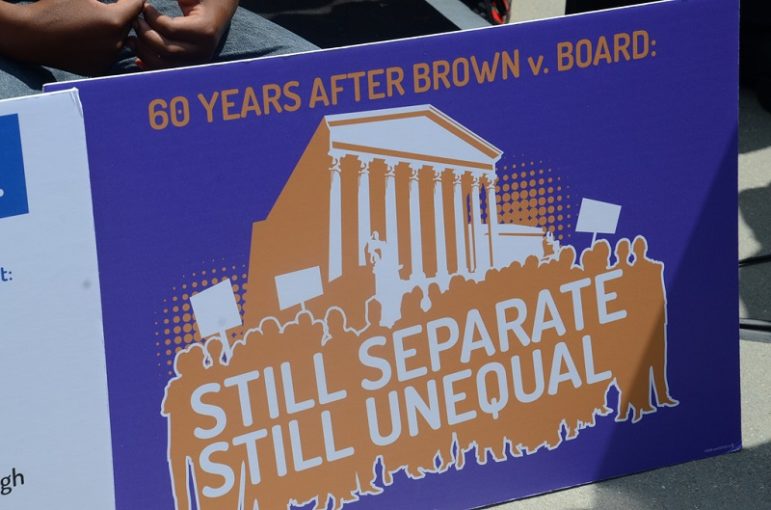

Sixty-two years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled “the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ [had] no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Yet if two recently released studies are to be believed, for too many children our public education system is becoming more segregated along both racial and economic lines.

On Tuesday, May 17th, the Government Accounting Office released a report on school enrollment patterns that found “from school years 2000-01 to 2013-14 (the most recent data available), the percentage of all K-12 public schools that had high percentages of poor and Black or Hispanic students grew from 9 to 16 percent.” Seen from another perspective, that of the Los Angeles Times, U.S. Department of Education data shows that “in the 2000-01 school year, 7,009 public schools were both poor and racially segregated. That number climbed to 15,089 by 2013-14.”

Just one day earlier, UCLA’s Civil Rights Project published a briefing paper from its ongoing look at race and public education. Their analysis of school data came to the following conclusion:

The share of intensely segregated nonwhite schools (which we defined as those schools with only 0-10% white students) more than tripled, rising from 5.7% to 18.6% of all public schools. Even as the resegregation was taking hold, there was a sharp decline in the percent of segregated white U.S. schools that have a tenth or fewer nonwhite students, dropping from 38.9% to 18.4%. The result of these diverging trends is that whites can perceive an increase in interracial contact even as African American and Latino students are increasingly isolated, often severely so.

When we recognize the connections between poverty, residential patterns, and race, these findings raise bright red flags when effective education is seen as the key to future success. According to Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA), ranking member of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, which had asked the GAO to conduct its study, “Segregation…[is] getting worse, and getting worse quickly, with more than 20 million students of color now attending racially and socioeconomically isolated public schools.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A recent op-ed in Education Week underscores the critical importance of this new data. “Policymakers increasingly recognize that stresses related to student poverty—hunger, chronic illness, and, in too many cases, trauma—are the key barriers to teaching and learning.”

Decades ago, the Supreme Court struck down the legal structures that enforced racially segregated schools. These new studies show that other factors have allowed new barriers to be built. Changing residential patterns, a still-unfair economic framework, and the growth of alternate forms of public education have combined to allow inequality to rear its ugly head. Disturbingly, the authors of the UCLA CRP brief see little effort being made to reverse course:

The challenge of segregation grows each year and takes on more urgency as nonwhite students make up half of all students, yet it has been a long time since it was approached with vision to further integration and to provide the needed resources to do so. Instead, we have spent decades trying another approach: policies that have focused on attempting to equalize schools and opportunity though accountability and high-stakes testing policies, not to mention the federal subsidization of entirely new systems of school choice, like charter schools, without any civil rights provisions. These policies have not succeeded in reducing racial segregation or inequality.

The resistance to change is well illustrated in local, state, and federal battles to fund schools in less affluent communities sufficiently to provide the same level of education as can be offered in more affluent areas. The intertwining of race and economic status now pits white, affluent communities against poorer communities of color in a competition for a limited amount of educational funding. And that argument is bitter.

Should funds be prioritized for those at greatest risk and in districts with the least resources to spend on education, even if it means some districts will receive reduced funding? Just this week, Sen. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee battled with U.S. Secretary of Education John B. King over how the federal government allocates funds specifically for boosting the education of low-income students. (Overall, the federal government provides about 10 percent of education funding, with the balance of funds provided evenly split between local and state governments). King’s proposed changes would result in more affluent districts losing current funds in order to assist areas in greater need, a change Alexander opposes vehemently. Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, described the dilemma a fixed education pie puts in front of policymakers: “We don’t want to hurt one school to help another school. We have to help all schools.”

If separate is truly unequal, then we must either be willing to spend more money so that no one needs to have less in order for some to get more, or we must accept the pain of those whom segregation has favored giving up some of their benefits to even the playing field. The social and economic barriers that separate our children cannot be allowed to remain and sentence some of our children to dim futures. It will take courage and investment, but it must be done.—Martin Levine