This article comes from the spring 2017 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, which addresses ways of thinking differently about a variety of issues affecting the sector.

When you use the word capital in the nonprofit sector, you must take the time to define your terms, because so far there is no thorough understanding of the structures of financial capital inside nonprofits. This lack of shared understanding is a big problem, because it is capital that helps organizations to both smooth out the inevitable rough spots and expand impact and improve quality.

Some of this capital exists in areas other than money—in the unpaid time people are willing to spend on the mission, in the social capital that an organization builds with stakeholders, and in things like reputation and clarity of purpose and fit with the environment—but this article discusses financial capital, which does not stand completely apart from these other types but is a structural support that needs to be much better understood and deployed by nonprofit board members, funders, leaders, and managers.

What It Is

A simple way of thinking about capital is as the type of financial resource that supports an organization for the longer term. This can be contrasted with the operating revenue that a nonprofit needs to operate day to day over shorter periods.

Of course, for a very long time among nonprofits, the word capital was used almost exclusively in relationship to a capital campaign, and it was largely understood as capital for brick-and-mortar (and related) costs. But current usage is more sophisticated, and lays out a number of types of necessary capital:

- Working capital for liquidity and reserves;

- Change capital (sometimes referred to as risk, growth, or innovation capital);

- Capital campaigns for hard assets; and

- Endowment in perpetuity.

In addition, capital is no longer thought of as needing to be primarily associated with a traditional campaign, but may be raised:

- Internally over time, or

- From external sources.

None of this is brand new, but our increasingly shared clarity about capital is—and the stronger that clarity gets, the easier it will be for all of us to raise capital, grant capital, and reflect capital in our financial statements.

Working Capital for Liquidity and Reserves

Working capital is necessary to most nonprofits even in stable times, in that it helps to smooth out the misalignments in the timing of revenue and cash outlay. This is the definition of liquidity. Liquidity allows an organization to pay its bills on time and not have to worry about vendors being unhappy or the organization being delayed in payroll or any other critical investment. A chronic lack of liquidity drains organizations of staff time, reputation, and social capital. It also obfuscates the real financial position of the organization. To operate confidently, organizations need a sense of security that they can meet their operating obligations without a feeling of crisis.

For more unstable times, we need a different sort or level of liquidity in a healthy reserve fund. Reserves help us to face and survive unpredictable but not uncommon problems such as loss of a revenue source or an unexpected need for an outlay—or, as many of us may remember confronting, a recession.

Change Capital

Change capital—sometimes referred to as risk capital, growth capital, or innovation capital—may include money for expansion, changes in strategy, and replenishment of depleted funds. If an organization can see an opportunity for greater impact through growth or innovation—and if it can lay out a clear case for how to get from its current state to a more desirable one—it may be able to raise capital to do so. Such efforts are inherently risky, as they are often based on strategy and assumptions. This is why some foundations refer to change capital as risk capital. In some cases, your business model may require regular recapitalization—as in the performing arts, where the product needs to be paid for before it’s ready for consumption and before patrons choose to pay for it. This is inherently risky, and repeatedly so. Or, maybe you’re in the mental health field, and there is some research and testing of a new approach that needs to be done. These are the kinds of things many organizations regularly must do in order to stay current with their environments and responsive to their own evaluations—and all of it needs capital.

Also in this category of change capital is a periodic need for replenishment. If an organization has had rocky operations in the past and has accumulated deficits, it may need to replenish some of those resources that have faltered. A good example of this would be the hundreds of arts organizations caught mid–capital outlay in the beginning of the recession. As mentioned above, performing arts organizations make those outlays quite often—for example, on scenery, rehearsals, and any number of other items—but if the economy goes very sour between the time an organization makes such an outlay and the time it stages the event, it may not reflect on the organization’s management in the least. Thus, while these needs may be due to internal issues, like a faulty business plan or inadequate technological capacity, they can also be driven by external circumstances, like a recession.

Sometimes, this manifests through the balance sheet, a statement of financial position for an organization, which in such cases would show that the organization is in a negative unrestricted net assets position—an indication that the organization is in need of replenishment.

In none of these circumstances does the capital need pose the same kind of ongoing requirement for funds as does operating revenue.

The capital for growth, expansion, and innovation is really capital for areas for investment and infrastructure (facilities, people, technology). An organization has a vision. It wants to be in a different place. The capital needed to get from here to there pays for infrastructure but also sometimes for an operating plug during a limited period. This gives a new revenue model a chance to catch up. So, it’s for a period of time when the organization needs some extra infusion of funds to be able to build these new capacities that it doesn’t have right now.

Without an understanding of capital structure, a declining position may not be clearly noted before pricey ground has been lost. If an organization has a building it has invested in, its unrestricted net assets may look very strong, because they include that building. But, in our definition of LUNA (Liquid Unrestricted Net Assets)—a concept that you may have been exposed to through Fiscal Management Associates (FMA) materials and webinars—we look at unrestricted net asset balances without that building. And, when an organization does that, it might find itself in what we call negative LUNA, which means that the organization has had these deficits, and oftentimes it’s not that clear—it’s not that transparent. But, for leaders of organizations that find themselves in that situation, it can be almost impossible to raise operating revenue to recover those accumulated deficits. Still, in such circumstances a nonprofit may be able to wage a one-time campaign to rebalance the organization’s infrastructure, replenish those resources that were invested in the past, and set the organization on a path to success. (A word of caution: this is a well one shouldn’t visit repeatedly.)

Despite what you may think, however, change capital is not impossible money to acquire. We at FMA have worked with organizations where grants have been made by foundations to do not only the replenishment—because that only gets us to zero—but also to build toward the future. So, there are ways not only to replenish through capital but also to combine it with growth and expansion. And those are a part of what we could call a capital campaign—a campaign for sustainability, the fund for the future, capacity capital. There are many different ways to describe what we refer to here as change capital.

Capital Campaigns for Hard Assets

In terms of capital campaigns for hard assets, it is important to emphasize that these are not just for construction or for building acquisitions. Capital campaigns that involve buildings also need to include two additional elements. One element is on the ramp-up side: these newly constructed buildings that are now up and running are not necessarily going to be fully utilized immediately—an organization may be doubling its capacity to deliver a program, and it may need some funding to get to the point where it can actually maximize the use of the building to fully cover its costs. Another component of a capital campaign that is critical is some level of reserve to cover operations in the future. The more that the organization can raise toward this reserve, the more peace of mind it will have when the building is ultimately up and running.

Endowment in Perpetuity

In some cases, endowment money that feeds investment income to the organization becomes necessary. With endowments, we encourage organizations to challenge themselves with the question: Do we have the capacity to raise sufficient funds such that the earnings from these funds would have sufficient impact on our operating results? A $100,000 endowment in the days that we’re in right now—and probably will be for some time in terms of interest rates—doesn’t really contribute much to operations, yet such an endowment is locked in perpetuity for use. In addition, we have seen several cases where the creation of an endowment has cannibalized contributions from operations and in the short term hurt the organization’s fundraising efforts. Grants for reserves and grants for change capital provide much more flexibility for the organization. Finally, an endowment can also be a component of the capital structure of an organization. Endowments generate revenue in perpetuity. So, the base of the endowment—the principal—is never touched, and the funding that is available comes from the residual income that the organization earns.1

How to Get It

Capital accumulation can happen in one of two ways. It can come from internal resources—for instance, when a nonprofit strategically grows a pool for investments and risk taking. Such internally developed funds may be accrued through budgeting surpluses—and, indeed, this is often how working capital has been accumulated in the sector. The second method is, of course, to raise funds from outside investments, particularly to act as capital not just to purchase equipment or space but also to grow an organization or to strengthen an organization’s operations as the business model is refined.

Internal Resources

An accumulated surplus for an organization is an internal resource that has accrued over time, and this excess represents the organization’s profit. The excess of revenues over expenses—or surplus—is absolutely critical for long-term sustainability. When organizations have a focused strategy to accumulate a certain level of surplus so that accumulation can be available for the right decisions at the right time, that is a source of capital. LUNA is part of an organization’s internal capital structure. Also—somewhat a cross between internal and external—there is the idea that organizations can at times leverage either free or low-cost resources that are available to grow the organization, whether it’s donations of time or of space. Those are often overlooked when we think about where our capital is coming from.

Outside Investments

Outside investments would normally come from foundations or major donors, and those outside investments are earmarked for things like we mentioned earlier, either physical capital or change capital—meaning for things that are going to be done differently in the future. Grants may also be given to provide liquidity through working capital or reserves.

An area of outside investment not always thought of as such is debt. In this context, debt may serve as a short-term source of working capital or as a long-term vehicle. In both cases, it represents leverage. An organization might have a mortgage—or, an organization might have a line of credit or might be interested in exploring a program-related investment, also known as a PRI.

The line of credit as a source of capital can have a lot of emotion attached to it. There are many board members who question the use of a line of credit in the nonprofit sector, and we often refer to this fear as having scars of war. They’ve been on nonprofit boards where the line of credit wasn’t managed as strategically or carefully as it should have been, and there’s concern. We believe that a line of credit is a necessary business tool, and any organization that needs to weather storms of timing in terms of cash should look at this as an option.

PRIs come in different forms, but in most cases a PRI is a recoverable grant that looks like a long-term debt instrument. In these arrangements, the third party (primarily foundations) is looking at this as a type of investment just like it would a grant—but the vehicle in this case is a recoverable grant, meaning that the organization will need to return those dollars at some point, and there’s a return on investment that the foundation is looking for, which becomes for the organization a cost of capital.

How to Record and Monitor It

In this next section we focus on recording and monitoring growth capital. Our focus is due to the multiple ways in which this capital is at times presented in audited financial statements, and the need to best correlate this external reporting with ongoing operating results as managed internally. We also believe it is important to connect this financial reality to external dialogue with funders who are investing in the growth plan.

Impact at a Point in Time

So, when we think about all these sources of change capital, we wonder how they show up in our financials. Some funds come in the form of debt, some are operating revenue, and some are additions to reserves. Where can we find all this, and how should you monitor your capital structure?

An organization’s net assets composition is one of the most important components of financial health and an indicator of capitalization. At FMA, we believe that understanding the net assets composition—unrestricted, temporarily restricted, and permanently restricted (also known as “endowments”)—and the goals for each is critical to creating an effective long-term capital plan for an organization.

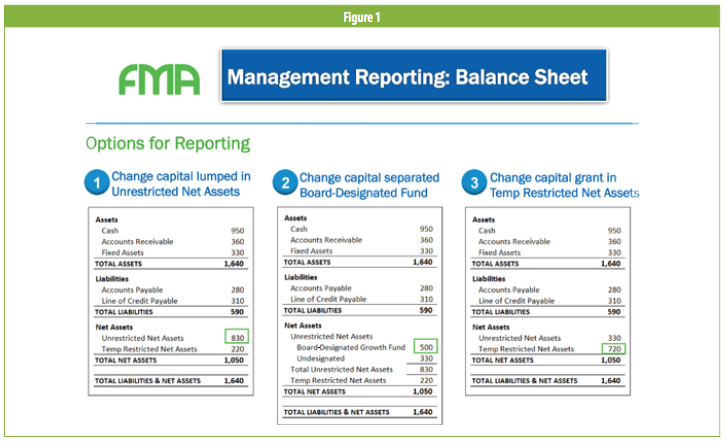

The following illustrates where capital may be found in the net assets section of the statement of financial position—also known as the balance sheet—recorded as of a point in time.

Change capital can be reflected entirely in the unrestricted net assets section of the balance sheet. Figure 1 shows three reporting options. In the first example, unrestricted revenue includes risk capital that had been received with no specific deliverables—just in support of the plan overall. As the surplus accumulates from one year to the next, the capital is a part of unrestricted net assets, until it is spent.

In the second example, the board set up a separate fund for the capital campaign, and this board-designated fund is broken out separately as a component of unrestricted net assets.

In the third example, the funder restricted the use of funds, such as for an evaluation system or technology, and these funds carry forward for several periods into the future—thus they would be deemed temporarily restricted net assets.

All of these examples are completely appropriate presentation formats. The key is to be able to articulate the capital story to outsiders and insiders, including the board, and show where this capital is recorded and what its ultimate use will be.

Impact in the Year of the Grant

There are a few ways to show the impact for the year in which the donation is received, which gets reflected on the statement of activities (often referred to as the income statement or the profit and loss [P&L] statement). The variations are a function of whether the capital is intended for activities that can be clearly allocated between operating and nonoperating.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For those of you who have been following the changes in the nonprofit accounting standards, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has finally released its new guidelines on the presentation of nonprofit financials, but these guidelines still have one element remaining to be resolved in a future phase—and that is the definition of operations. The clarification of operating versus nonoperating sources of funds has brought with it much difference of opinion among the accounting profession, nonprofit leadership, and the funding community, so that’s to be continued. Given that the FASB hasn’t figured it out, we’re okay with accepting the confusion as to the correct way of showing operating versus nonoperating results.

While there are different interpretations of operating versus nonoperating funds out there, organizations should be consistent in how they present their capital activities, and should be able to explain them. The following examples illustrate various ways to represent operating expenses and related revenue in the budget and for management reporting purposes.

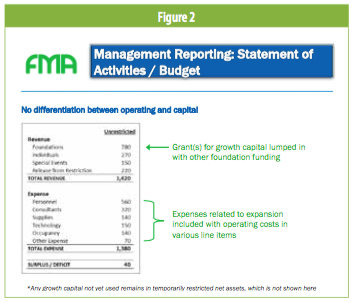

In Figure 2, the actual dollars that come in for capital have been grouped with operating results, because it’s difficult to differentiate these revenues and expenses designated for an overall growth strategy with ongoing activities. It’s very important for the financial story to explain the purpose of the capital, how capital’s been utilized, and the activity to date. It’s also very important to keep an eye on any milestones associated with the plan.

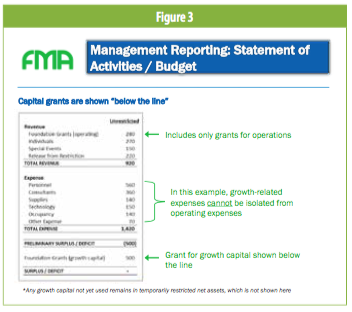

In Figure 3, the expenses related to the capital cannot be separated out, but a grant was specifically given in support of a growth strategy. The grant for growth capital is therefore shown below the line of operating results, and the presentation is clear with respect to how much of the growth capital has been used in the current year. In essence, the organization is building a deficit, in that it has operating revenues that it is accounting for, and then it has expenses that can’t be isolated from growth-oriented activities—such as expenses related to talent development or fundraising.

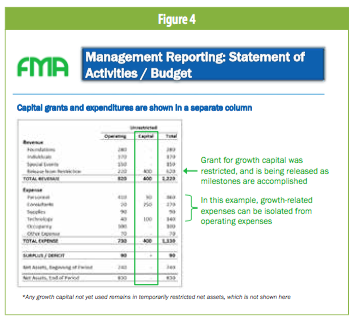

Where it is possible to separate the expenditures related to the growth trajectory or the milestones in a capital campaign, an organization might present its capital grants and expenditures in a separate column (see Figure 4). This shows activity through satisfaction of the terms of restricted grants or just general operations. The FASB’s goal is for nonprofits to distinguish operating results from nonoperating results, so this idea of a separate column might very well be where they end up.

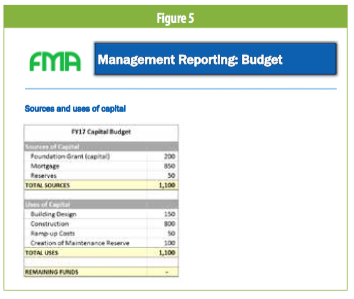

Figure 5 illustrates the idea of capital for physical property, such as buildings. Many organizations have operating budgets, and they may be funding depreciation over time but they don’t necessarily have capital budgets. The sources and uses of their capital needs would look something like the below, and on an ongoing basis the organization would continue to follow the concepts of capital budgeting for replacements and new acquisitions in the future.

Monitoring the Growth Plan

When capital represents funding for a growth or scaling campaign, the mechanisms for monitoring results become critical. Growth campaigns are based on best estimates of operating costs at levels of scale never experienced by the organization. The plan is necessary as a basis for initial investment, but the monitoring framework needs to allow for the likely possibility that the plan may need to change as time goes by to reflect lessons learned from the scaling efforts.

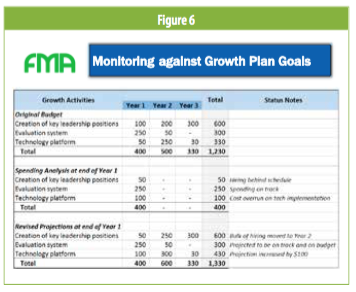

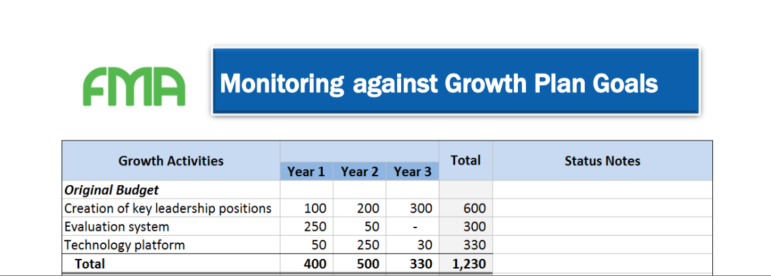

Figure 6 is an example of a report format that is critical to understanding and monitoring an overall growth and scaling plan. It’s not used as the organization’s annual budget; rather, it is a budget document that is critical for planning and capital fundraising efforts, reporting progress internally and to investors, and helping to communicate strategic changes in the plan along the way to stakeholders.

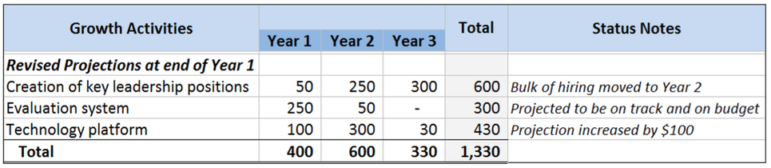

Establishing an original budget for a scaling plan. Typically, when you first do a growth plan, you develop an original budget for three years and give your best guess as to what it will cost to achieve the goals that you have. As the breakouts from Figure 6 show (below and following page), this scaling plan had three key deliverables over a three-year period for a $1.2 million growth-capital campaign. These three-year budgets had lots of detail and assumptions that went out to funders explaining what the plan was and what it would cost. We can’t stress enough that documentation of those assumptions is critical. Organizations are giving it their best shot, but they’ve certainly never done this before, and the funders don’t necessarily know whether the numbers are exactly right or wrong, because they are unique to each organization and to where each organization is and where it wants to be.

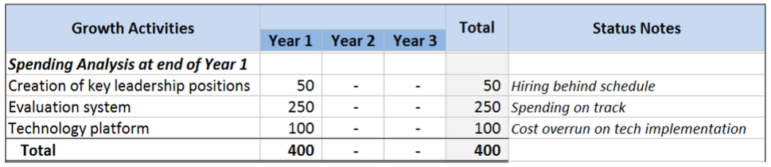

Spending analysis at the end of year one. Thus, the assumptions behind the growth plan are absolutely critical as benchmarks for the future—so that after the first year or six months, however often you need to monitor it, you can ask yourself how you are doing. You do a spending analysis at the end of year one. An organization might ask: How are we doing with the creation of the key leadership positions? Well, we’ve only spent $50,000; we’re behind. We haven’t been able to find the chief development officer that we were looking for. The evaluation system? We’re right on track. We’re spending and we have an accounting system that tells us that. We’re able to track that these costs for these vendors are for the evaluation system. And then, lastly, the technology platform actually cost us $100,000 in year one. Is it an overrun? Are we spending more than we thought, or is it a timing issue? Are we accomplishing this deliverable sooner than we thought?

These are critical questions for an organization vis-à-vis monitoring internally how they’re doing against their plan, but it is equally as important to be able to speak to their funders about the growth plan and say, “Here’s where we are.”

So, at the end of year one, an organization might conclude: We thought we were going to be able to do this for $1.2 million. Here’s what we learned from year one. We’ve refined our thinking, and let me tell you what that means for changes in the future—years two and three. That’s the third part of this analysis.

Revised projections at the end of year one. Finally, you want to do a revised projection at the end of year one. An organization might decide: In the case of the leadership positions, we’re going to move the hiring to year two and year three, and we’re still going to be able to do it with the $600,000 we expected. As far as the evaluation, we’re on track exactly as we planned it. As concerns the leadership positions, there will be more in year two, but we’re fairly confident that with the reaching out we’ve done and the candidates we have in line for these positions, we’re going to be able to catch up and be on target for the leadership hiring. And, lastly, with respect to the technology platform, we thought it was going to cost $50,000, but it cost us $100,000, and it’s not going to go down in the future. We have to accept that we’re going to need more money for technology, and we need to think through what the total cost will be. So, based on this growth plan and its first-year results, it really needs to go up to $1.3 million from $1.2 million.

…

This is the financial story of the growth plan, and this is the financial story of the capital campaign as it relates to growth. Armed with this analysis, an individual raising dollars for an organization can go to a funder, and say, “Here’s where we are, and let me tell you why we need to increase the amount of the investment in future years.” Funders who choose to invest in capital are partners with their grantees. They think about how they can be supportive. They ask themselves, “What are the right questions to ask that are strategically inclined so that we’re working toward a common goal?” This is not a compliance framework; it’s a partnership framework. And, for the organization that’s carrying out that plan, it’s really important that this one-pager—which looks fairly simple but has a lot of thought behind it—make the difference in that communication, as the story often evolves. If in year one the organization is off, that doesn’t mean it did something wrong. It doesn’t mean it made a mistake and the funder will not be happy. It means that here’s what it learned and here’s how it’s going to adjust for that in the future.

So, we encourage you: if you’re thinking about a growth campaign, have one in the works, are building one, or are in the middle of one, come back to these framing questions and ask yourself what it would take for you to understand and clearly articulate the financial story around your plan.

We’ve gone through the different sources of capital, the different purposes, the different ways to report on it. Raising dollars is not just fundraising for the operations for the year—it’s for long-term sustainability, for an ability to grow and experiment and take risks. It’s a longer-term framework. It’s very difficult to seek this type of capital without a long-term view toward the strategy that you want to implement. If you can’t tell your multiyear financial story, it makes it very difficult to raise capital. On the flip side, if you have a well-articulated strategy with a well-documented financial plan, you’ll be in a much more successful position going out and raising the capital that you need not just to operate but also to thrive.

Note

- For more on reserve grants, see Hilda H. Polanco and John Summers, “Keeping It in Reserve: Grantmaking for a Rainy Day,” Nonprofit Quarterly 23, no. 1 (Spring 2016).

Some Capital Questions Answered

The Nonprofit Quarterly asked Hilda Polanco to answer some questions about crucial capital strategy for nonprofits…

What is the benchmark for an accumulated surplus or for reserves that people are supposed to have in hand?

Hilda Polanco: I think the right answer here is, it depends. Of course, that’s not the answer we want to hear, because we need to know a number. So, it depends on the business model. It depends on how urgently an organization may need to respond. A relief organization needs to have a higher availability of reserves than some other types of organizations, because it may need to react very quickly, without much time to raise needed funds. But putting aside exceptions like relief organizations or other organizations that need immediate cash in large sums, for regularly operating organizations, the rule of thumb (for bankers and others who think about this) is three to six months. But three to six months of what? Three to six months of total operating expenses is the most conservative estimate. What that would mean is that if the world were to stop in some significant way—revenues stop coming in, the perfect storm happens—we have three to six months of operations in our reserves.

The issue with that is that sometimes organizations have grants that fund specific activities, and they’re thinking: If I didn’t have those grants, I wouldn’t incur those expenses. So, an organization in this position might modify the base for calculating the number of months to have in reserves to only include “core” operating expenses, and decide what it would take for the organization to responsibly cover a period of three to six months of its core operating costs. And then there’s my definition of adequate core operating expenses that I share with folks when we are together in trainings, which I often think of as, what would it take for the executive director to sleep at night? And risk tolerance varies. I’ve had EDs tell me, “It takes a year of core operating expenses for me to sleep at night,” and others say, “Three months is all I need—I can make it with three months.” So, every organization has to make that number their own. It’s the number that’s going to shift someone from crisis to long-term strategy and then grow from there. So, that would be my minimum number: for some, it’s one month or two months of payroll, two months of rent, and they can sleep at night. It depends.

How do you position an organization to ask for change capital? Under what conditions do you think that it is awarded?

HP: I think the positioning is about focus and clarity. So, if an organization raises money to run programs to deliver its mission, that’s what funders, individuals, foundations support. And they support that year’s operations—and, if that’s all that we can position, they support the operations for the year, number of people served. That’s what we can raise money for. If we’re positioning ourselves for change capital, for risk capital, we need to have a vision of that. So, I think a first step toward a capital campaign is that there needs to be a plan where an organization allows itself to dream beyond the restrictions of available resources today: If I could develop our curriculum in this way to get outcomes of these types, what would that take, and how would I know that I’ve succeeded when I get there? So, clarity around what the outcomes are. That’s what investors are going to invest in—those outcomes. And, to get there, what will it take? Where do I need to develop my infrastructure? What do I need to do in the form of experimentation?

I think it’s a process that is very different from one’s regular operating budget planning, which is somewhat focused on the here and now. This is giving the organization the permission to think beyond the current and then articulate that in a well-positioned plan. A growth campaign is going to be funded by those funders who have already invested in you and have seen the outcomes and believe in them. It’s somewhat unusual for funders to invest in growth capital for organizations they’ve never funded before. Having said that, there is a growing level of philanthropy that focuses on identifying a good idea and then helping an organization scale that. With that clarity, I think the organization will be best positioned to go after those grants. That’s assuming that this question is about the capital campaigns in that context, not working capital or any of the others.

How do you convince foundations to replenish capital when you’ve had a number of bad years, and how do you convince them that some of those bad years could perhaps be put at the feet of not great management, or what people perceive as not great management?

HP: I think the answer to that is very similar to the one we just covered, which is a mix of clarity, cost, and outcome. So, first, the clarity in this case may require a bit of humbleness—it may require that you say, “We are in an accumulated deficit of $75,000, and we know how we got there.” This statement shows that you understand how you got to that deficit, and as such, you’re more likely not to repeat it in the future. So, understanding what caused the deficit would be the beginning of clarity.

Second, the clarity would be in understanding what you are doing differently that is going to ensure that the deficit is not a repeatable offense in the future. If the issue that caused the deficit is about management, and that’s already evident to the funder and to the leadership, then how is management changing? How is the board engaging to ensure that those activities that caused the deficit have been turned around? That’s only part of the way. Now, the question is, how is this organization going to be sufficiently strong and sufficiently strategic to turn the corner with those past challenges and go forward in a positive way? And that goes back to, what’s your plan? There is a reason the organization exists. It may have had positive years and then had a few negative years. Well, let’s come back to the positive. What is it about its approach to its work that allows it to achieve those outcomes? Once you’ve gone beyond explaining the past and indicating how the future is in a different direction, then it’s a growth plan like any other growth plan. We’ve worked with funders who have said, “Tell me the number. What is the number that is going to allow this organization to rebalance (meaning replenish) those deficits and go forward in a strategic way? I don’t want to fund the number that will just make them whole; I want the number to make them whole and position them for success in the future.” And that organization needs to know what that number is—not only the accumulated deficit, which comes right from the financials, but also what the long term will be.

Third, when you’re recovering from something that didn’t go as well as you hoped, there more than ever you need clarity—a partnership between the staff and the board for ultimate outcome. So, how is the board a part of that—not only on paper, but also how is the board a part of those asks and part of the commitment that that potential funder could see?

What are the barriers to building strong balance-sheet health?

HP: One of the barriers, I think, is not understanding the business model and the revenue and expense drivers that get an organization to its final results for the year. So, if we understand that we’re delivering services within our means and we’re accepting grants that cover their costs—and if they’re not, we’re raising the difference—we have to have an eye on the model, because the balance sheet is not an accident; it’s an outcome of what has transpired over the life of the organization. So, stabilizing the business model so that the organization generates sufficient revenue to cover its cost plus—that would be the most critical step to having a strong balance sheet. And I’ll end this answer by saying, if the revenues and expenses in the budget that you present to your board for approval are absolutely equal—which I see very often—then the message is, we have every intention of spending every dollar we raise, and we are taking no steps toward strengthening our balance sheets. So, a first step toward strengthening your balance sheet is making sure that you’re in your budget and setting the parameters for the year—budgeting for a surplus, which is meant to increase the strength of your reserves.