April 25, 2018; The Root and the New York Times

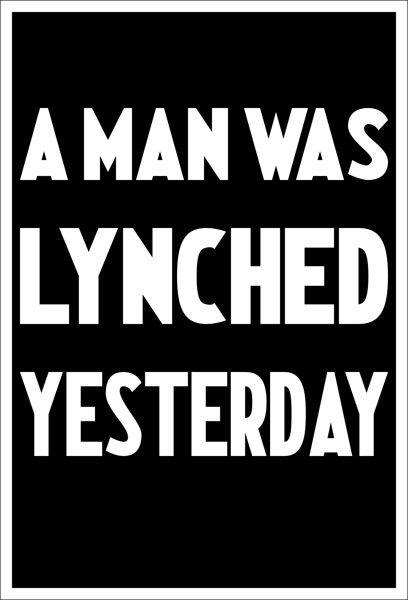

The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice both open today in Montgomery, Alabama. According to the New York Times, the exhibit is the first to recognize the atrocities of white supremacy in the US.

NPQ wrote about the development of this initiative last year (here and here). The Root’s Angela Helm visited the sites (the museum is in a former slave warehouse) and describes them this way:

The serene, well-designed memorial to the more than 4,000 African-American lynching victims is all about historical context. The somber, sacred space, standing atop a hill, begins with slavery. When one enters, after passing a quote by King, visitors first encounter a sculpture of seven African men, women and children chained in various states of bondage, designed by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo.

One then goes up a slope, with placards giving context to lynching. (Nearly 25 percent of those lynched were accused of sexual assault, nearly 30 percent accused of murder. The means of death ranged from hanging to shooting to burning to stabbing to beating to drowning.) And at the very top of the hill, one encounters the first monuments at eye level.

As one rounds the square space, the ground begins to slope down, illuminating each of the 800 corten-steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror took place. With each corridor, the monuments with the names of those killed begin to rise. Until they are above you, hanging.

To the side, there are stories of some of the individuals: “Mary Turner was lynched, with her unborn child, at Folsom Bridge in the Brooks-Lowndes County line in Georgia in 1918 for complaining about the recent lynching of her husband, Hayes Turner.” Or “Rachel Moore was lynched in 1921 in Rankin County, Mississippi, by a mob searching for her son-in-law.”

The list goes on, insignificant act after insignificant act ending in death, eerily similar to the random activities that today, too, result in death for too many Black people in the US—and around the world, really. Or, incarceration; Helm goes on:

There are other holograms, too, a bit farther down, but this time you sit down and pick up a phone, as if you are visiting a prison. And the prisoners, now in color, tell you their stories. Like Robert Caston, who, sitting across from you, recounts that at 17 years old, he got a life sentence to be served at the notorious Angola State Prison in Louisiana, which was built on an actual plantation. He speaks about how a sound dictated every aspect of his waking life.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

[…]

He spoke about…how his life was one of pure subjugation.”

The six-acre park contains “a field of identical monuments.” The memorial encourages counties to claim their column and address their history and impact of racial subjugation, over time reflecting which ones are dealing with their histories and which are not.

The nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative created both the museum and memorial after years of research into racial inequality and economic injustice in the US. The museum houses the most comprehensive data on lynching in the US and uses new technology and storytelling to bring it to life. The main story, though, is that racial subordination is codified, enforced by violence, and evolves: from slavery to lynching, to Jim Crow and segregation, to urban poverty, to mass incarceration. Underlying it is a belief in a racial hierarchy.

Of course, many people, especially people of color, already knew much of this. But it is important for society at large to understand the evolution of racial domination strategy in the US, the ways it animates our economic realities, and shapes black bodies.

Helm notes that Montgomery is a city of racial dichotomy; it is both the “Cradle of the Confederacy” and the “Birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.” By the 1860s, Montgomery, which lies on the Alabama River, was the “entry point to slavery in the ‘lower South.’”

Reinforcing EJI’s message, last week, former NFL quarterback (and social justice hero) Colin Kaepernick received an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award for his “kneeling protest of racial injustice, which began a sports movement and might have cost him his job.” In accepting the award, Kaepernick said, “Racialized oppression and dehumanization is woven into the very fabric of our nation—the effects of which can be seen in the lawful lynching of black and brown people by the police, and the mass incarceration of black and brown lives in the prison industrial complex.”

The Associated Press reports, “Amnesty hands its award each year to a person or organization ‘dedicated to fighting injustice and using their talents to inspire others.” In a way, though, what a waste. What if Black people could just live for themselves? —Cyndi Suarez