February 18, 2019; Barron’s, “Penta”

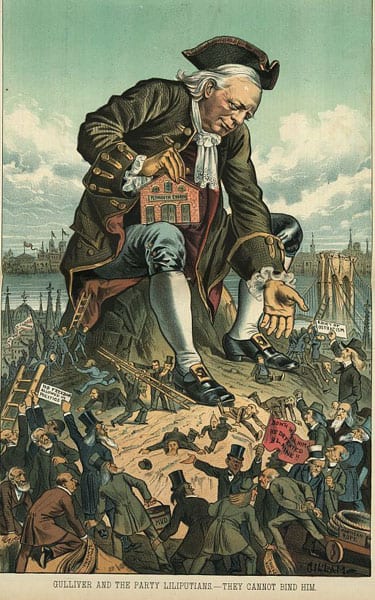

Is a donation a gift or an investment? Does it represent a donor’s expression of trust and support for the recipient nonprofit’s mission, leadership, strategy, and tactics? Or is it more transactional, representing the donor’s desire to influence and control? These questions may not be unique to this moment, but they have become more critical as a new wave of mega-donors has emerged—donors whose wealth has intensified the power dynamic between donor and organization.

According to Fang Block, writing in Barron’s Penta section meant for quint-millionaires, the organizational value of larger donors goes beyond the size of their gifts, as large as they may be. “Compared to mass donors or even high-net-worth donors, the ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) population tends to leverage their social capital—their reputations and business track records—in addition to their own private funds, to find solutions to causes they are passionate about.” Not only can they make gifts individually that can be transformative for even very large organizations, they bring others of similar wealth and prominence along.

Social and political capital, along with wealth, can be invaluable for organizations, but comes with risk. Jeffrey Henig, a political science and education professor at Columbia University and a co-editor of the book The New Education Philanthropy, describes a change in philanthropic approach that comes with the power to influence: “The more strategic philanthropy that we’re seeing now…combines research and advocacy with a deliberate attempt to use their donations to change public policy.”

Carol Kroch, the national director of philanthropic planning for Wilmington Trust, tells Barron’s that “large-scale philanthropy is almost like starting a business.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For example, wealthy donors might have a detailed gift agreement with institutions they give a lot of money to. [Smaller donors] might donate to a food bank…their ultra-wealthy counterparts might be involved in tackling the larger issue of food insecurity.

The positive in the power of large donors was described by Beth Renner, head of philanthropic services for Wells Fargo Private Bank. Large donors “have more resources to deal with the type of philanthropy that’s more complex and transformational.” And yet, as NPQ has seen, these benefits come with dangers need to be carefully considered.

With the ability to provide significant amounts of money, particularly in an era of more limited public funding, large donors can set societal priorities that reflect very personal interests. Their power is further magnified because the structures mega-donors use to apply their wealth charitably “have unparalleled freedom to select and pursue any agenda.”

While, as Block notes, “donors, no matter what wealth tiers they belong to, share a great deal of common ground in terms of philanthropy,” the power shift that comes when donors combine wealth and influence with an investment mentality threatens the very basis of the nonprofit sector as a key element of a vibrant democracy. As Ruth McCambridge observed, “If we believe that we need a sustainable nonprofit economy that is broad-based and accurately reflective of the needs and ideas and dreams of the whole of our population, we need to consider how to maintain and build that bond with our many donors, in pursuit of a real democratic future.”

Individual organizations will weigh this balance as they set their fundraising strategies and respond to donors. They can fight to keep a broad base of small donors, and they can try to limit the power and influence of larger donors. Yet, if one sees large donors as a threat, we have gone beyond a time when individual organizations, big or small, can chart their own course and remain stable. Policy changes that affect how the entire sector and the way individuals can use their wealth may be necessary. It will take courage to risk alienating wealth in order to challenge their ability to control. It is a conversation we need to be ready to have.—Martin Levine