April 15, 2019; New Yorker

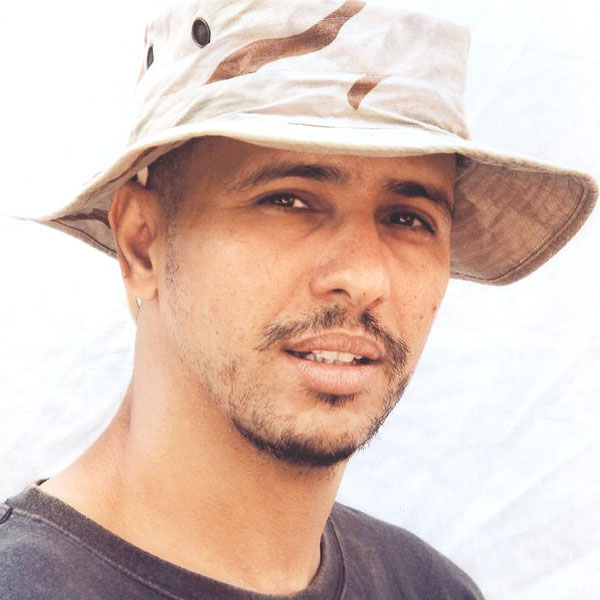

In the New Yorker, Ben Taub tells the story of Mohamedou Salahi, a person once deemed the US military’s “highest-value detainee” at Guantánamo, but who was released after 14 years in captivity without charge in October 2016. When taken into custody, Salahi was 30. Salahi penned the book Guantánamo Diary while in captivity.

The story of Guantánamo is about many things, but one of its most important effects has been to chisel away at US democratic values. Guantánamo is largely ignored these days. At its post 9/11 peak, it housed about 780 prisoners; today, 40 remain.

But the damage to civil society remains. As Kristine Huskey, now a law professor at the University of Arizona, wrote in the University of New Hampshire Law Review in 2011, “In a pre-9/11 world, a ‘Guantánamo’ and the idea of ‘detention without trial’ would have been seen as decidedly un-American and a violation of our democratic values. Over the last decade, however, Guantánamo” and the practice of long-term detention without trial for terrorism suspects (or, “preventive detention”), have evolved into institutions of American society that are now perfectly acceptable, indeed desirable to some, and of little concern to many.”

Of course, a nation founded on the practice of slavery and genocide against Native Americans—and which imprisons people at a larger per capita rate than anywhere else in the world, and where that imprisoned population is disproportionately of color—is hardly a paragon of democratic virtue. But Guantánamo is important both for its high profile and because it helped legitimate holding people in custody without charge indefinitely. A thread can be traced from the indefinite detentions at Guantánamo to those of immigrants today, a practice upheld by the US Supreme Court just a month ago.

As Taub reminds us, Guantánamo is a legacy of the US occupying Cuba in 1898; afterward, the US insisted on leasing an island base from Cuba for a trivial $4,085 a year. (For decades, Cuba has called for an end to the lease and has left US checks uncashed.) Salahi provides a detailed account of the conditions he faced there:

The cell—better, the box—was cooled down to the point that I was shaking most of the time. I was forbidden from seeing the light of the day…for the next 70 days, I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping.

Salahi was also subjected to 20-hour-long interrogations. “You know, when you just fall asleep and the saliva starts to come out of your mouth?” Salahi explains. “No prayers, no information about the direction of Mecca. No showers for weeks. Force-feeding during the daylight hours of Ramadan, when Muslims are supposed to fast.”

Salahi had a sciatic-nerve condition, which interrogators exploited. A Red Cross delegation that visited Guantánamo reported that “medical files are being used by interrogators to gain information in developing an interrogation plan,” notes Taub.

Salahi was groped by female interrogators and was threatened with rape. He was denied food some days and forced to vomit on others. He was beaten and at least seven of his ribs were broken. He was falsely told that his mother was in custody and would be brought to Guantánamo.

“Had I done what they accused me of, I would have relieved myself on day one,” Salahi wrote in his diary. “But the problem is that you cannot just admit to something you haven’t done; you need to deliver the details,” he added. After countless hours of questioning though, Salahi writes he had “a good idea as to what wild theories the government had about me.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Taub details some of Salahi’s “confessions”:

“I came to Canada with a plan to blow up the CN Tower in Toronto,” Salahi wrote.… He listed his accomplices and added, “Thanks to Canadian intel, the plan was discovered and sentenced to failure.”

[…]

He drew organizational charts, with the names and operational roles of key figures, and supplied intelligence on jihadi cells and safe houses all over Europe and West Africa.”

Salahi figured he ended up in Guantánamo because of a similar false confession. Salahi writes, “I felt so bad, and kept praying silently, ‘Nothing’s gonna happen to you, dear brother.’”

For Salahi, cooperation brought “comfort items,” including a pillow, soap, towels, books, a television, a PlayStation, an old laptop, a prayer cap, and prayer beads. Taub adds that, “One day, Salahi started requesting paper from his guards. A court ruling had given Guantánamo detainees had access to legal representation, and so, over months, Salahi drafted a diary of his detention in letters to his lawyers, Nancy Hollander, Sylvia Royce, and Theresa Duncan—466 pages.”

In 2012, Salahi’s lawyers won a seven-year legal battle to declassify his diary. The scanned pages were sent to Larry Siems, a writer and a human-rights advocate, who edited the manuscript, which was published in 2015.

Even after Salahi’s release to his homeland of Mauritius in October 2016, his freedom remains limited. He’s still denied a passport. Salahi needs gallbladder surgery; a German hospital says it will pay for both the surgery and a year’s rehabilitation, but he can’t travel there.

Speaking by Skype at an Amnesty International gathering in Washington, DC, Salahi observed, “Everything that happened to me—everything I witnessed in Guantánamo Bay—happened in the name of democracy, in the name of security, in the name of the American people.”

The message the US sends the world through Guantánamo, Salahi says, is “that democracy does not work—that when you need to get down and dirty, you need a dictatorship.” It’s a message reinforced by the many US practices that fail to respect human rights at home and abroad. Guantánamo, in short, reminds us of the violence hidden beneath supposed US democratic practice.—Steve Dubb