January 23, 2019; Daily Journal

Despite a Republican-controlled House, Senate, and governor’s office, the Mississippi legislature’s first major bill signed this year was a Democrat-led initiative. Blessed with overwhelming support, the bill makes it possible for the state’s 25 electric co-ops to now get into the business of providing broadband to their rural members. The bill passed unanimously in the state senate a week after it passed the House on a 115–3 vote. Governor Phil Bryant has pledged to sign the bill into law.

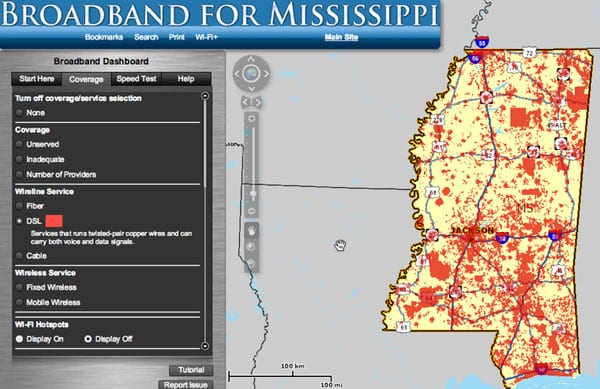

This rare bipartisan action was the result of an astute outreach campaign by Democratic Public Service Commissioner Brandon Presley to turn the paucity of internet service in rural Mississippi (the state ranks 49 out of 50 in connectivity, with an estimated 30 percent lacking access) into a populist wave that silenced the usual opponents, the cable industry and the big telecoms.

As Geoff Pender, writing in the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, explains:

About a year ago, [Presley] started working the rural broadband issue hard, tapping into some pent-up frustration in rural Mississippi.

He created a task force that ended up with 1,310 members over 33 counties. That, my friends, is a task force sure to get any elected politician’s attention.

He got 60 county boards and 70 city councils to pass resolutions in favor of allowing rural co-ops to provide internet service. That, too, is something guaranteed to get the full attention of elected lawmakers. They started getting calls and letters from their constituents.

At first, the electric co-ops themselves were sorta lukewarm on the proposal. They succumbed to the irresistible grassroots force Presley amassed. He brought Farm Bureau, Realtors, AARP and other groups on board, enough lobby might to counter cable and telecoms.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Pender adds that key to Presley’s success was making clear that he would not seek higher office, which made it much easier for the Republican governor and state legislature to get on board and share in the credit.

Few dispute that fast connectivity is essential for a community to survive and prosper—whether for economic development, health, or education—and it’s the nation’s rural areas that are most challenged. Only four percent of urban Americans lack access to broadband service, versus 39 percent of rural Americans (that’s 34 million people). Telecom and cable companies typically avoid investing in rural lines because, they say, it is too expensive to bring equipment and service over long distances to so few people. Indeed, the rural US makes up only 14 percent of our population but covers 72 percent of our land area.

Hugely disparate rural access to critical infrastructure is not a new issue for this country. While 90 percent of urban dwellers had electricity by the 1930s, only 10 percent of rural dwellers and farms were wired. Private companies hadn’t been interested in building costly electricity lines into the countryside and assumed the farmers would be too poor to buy the electricity once it was there. In 1936, in the depths of the Depression, Congress under president Franklin Delano Roosevelt passed the Rural Electrification Act (REA) to provide low-cost loans to build electrical distribution systems in isolated rural places. It quickly became clear that while established investor-owned utilities were not interested in this new program to serve sparsely populated places, farmer-based cooperatives were, and by 1939, the REA had helped establish 417 co-ops, serving 288,000 households. By the time Roosevelt died in 1945, an estimated nine out of 10 farms were electrified. Today, about 900 electric cooperatives serve much of rural America.

It would seem natural that these same electric cooperatives would take the lead today in bringing broadband to the 34 million rural people without it, and that both the federal and state governments would be willing partners. Yes, approximately 100 electric co-ops are working to expand broadband access in rural America. But that’s only 100 out of 900. What’s the problem? Some states discourage or ban electric co-ops from engaging in internet projects. In North Carolina, for example, a 1999 law prohibits the state’s 26 electric co-ops from using funds from the US Department of Agriculture (the locus of most rural utility programs) for broadband infrastructure. And in 2011, Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink lobbied the newly Republican-led General Assembly to pass a law limiting the authority of local governments to build networks. Though Georgia doesn’t specifically forbid co-ops from getting into broadband, its lack of legal clarity is a barrier. Tennessee’s co-ops were barred from offering internet services to their members until the passage of the Tennessee Broadband Accessibility Act in 2017. And Mississippi, until January 24, 2019, restricted its co-ops from engaging in any business other than electricity.

What swung the pendulum in the Magnolia State? A key factor is the availability of significant new federal resources for rural broadband. Our last approved federal budget (signed in March 2018) included a $600 million broadband loan/grant pilot and the 2018 Farm Bill authorized $350 million annually in grants and loans for rural broadband. States like Mississippi don’t want to miss out on these free or low-cost dollars. And then there’s the state-next-door-competition. Mississippi’s Public Service Commissioner Brandon Presley noticed that Alabama’s Tombigbee Electric Cooperative, just 14 miles from the Mississippi state line, is undertaking a $38 million project to deliver high-speed internet, so he brought 46 members of the Mississippi Legislature to Hamilton, Alabama, to show the progress this electric co-op has made.

“If they can make this happen in Alabama through their electric cooperative, there’s absolutely no reason except this arcane law that we can’t do it in Mississippi,” said Presley.

The path, however, is still not crystal clear for the nation’s locally rooted infrastructure cooperatives to solve the broadband challenge. The 2017 federal tax code change that now requires corporations (including cooperatives) to include government grants in the calculation for the member income test could imperil a co-op’s tax-exempt status. And there’s always the question, once connectivity is available, of whether enough local co-op members will want to sign on and pay for broadband service. But that’s a familiar democratic challenge for a co-op’s board and management, not one created by Congress, the state legislature, or the telecommunications giants.—Debby Warren