Since 2020, over 1,300 corporate firms have pledged to invest over $340 billion in racial justice. But these pledges are self-reported and self-enforcing. Two years ago, the Washington Post analyzed some $49.5 billion in pledges reported by the top 50 firms and found that “more than 90 percent of that amount—$45.2 billion—is allocated as loans or investments they could stand to profit from, more than half in the form of mortgages,” demonstrating, the Post reporters added, the “limits” of corporate efforts to address structural racism.

Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) have a mission to counter redlining and support lending in low-income and BIPOC communities. Yet even among CDFIs, the track record is highly imperfect. Now, two organizations from the CDFI sector have come together to address this issue and offer a way to measure progress.

“I think a major critique of CDFIs, especially right now, is that they operate a lot like banks.…They should be more creative.”

As Risa Blumlein Keeper, the interim codirector of catalytic capital at Community Vision, a Northern California-based CDFI, said to NPQ, “Over the last couple of years, what I have observed doing this work is that a lot of times there will be a commitment to invest in Black communities, but [the money] ends up going to White communities. Someone will say this money is intended to support the Black community, but we are going to give it to a White-led organization with a low-paid Black staff.”

Facts like these led Community Vision to partner with the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs (the Alliance) to develop some “rules of the road” as to what counts as supporting Black communities. Chavelle Sangokoya, Alliance vice president of programs and initiatives, concurred with Keeper’s analysis. “I think a major critique of CDFIs, especially right now, is that they operate a lot like banks,” Sangokoya said. “They should be more creative in how they finance projects.”

Lenwood Long, CEO of the Alliance, added that the partnership had proceeded smoothly, and he found Community Vision to be a “kindred spirit.”

According to Sangokoya, the process of developing the scorecard has been “iterative.” In addition to the ongoing conversations between the Alliance and Community Vision, this involved considerable outside consultation. Catherine Howard, CEO of Community Vision, said that in particular there was “[a] lot of conversation with Black leaders,” especially in the San Francisco Bay Area, where Community Vision is headquartered.

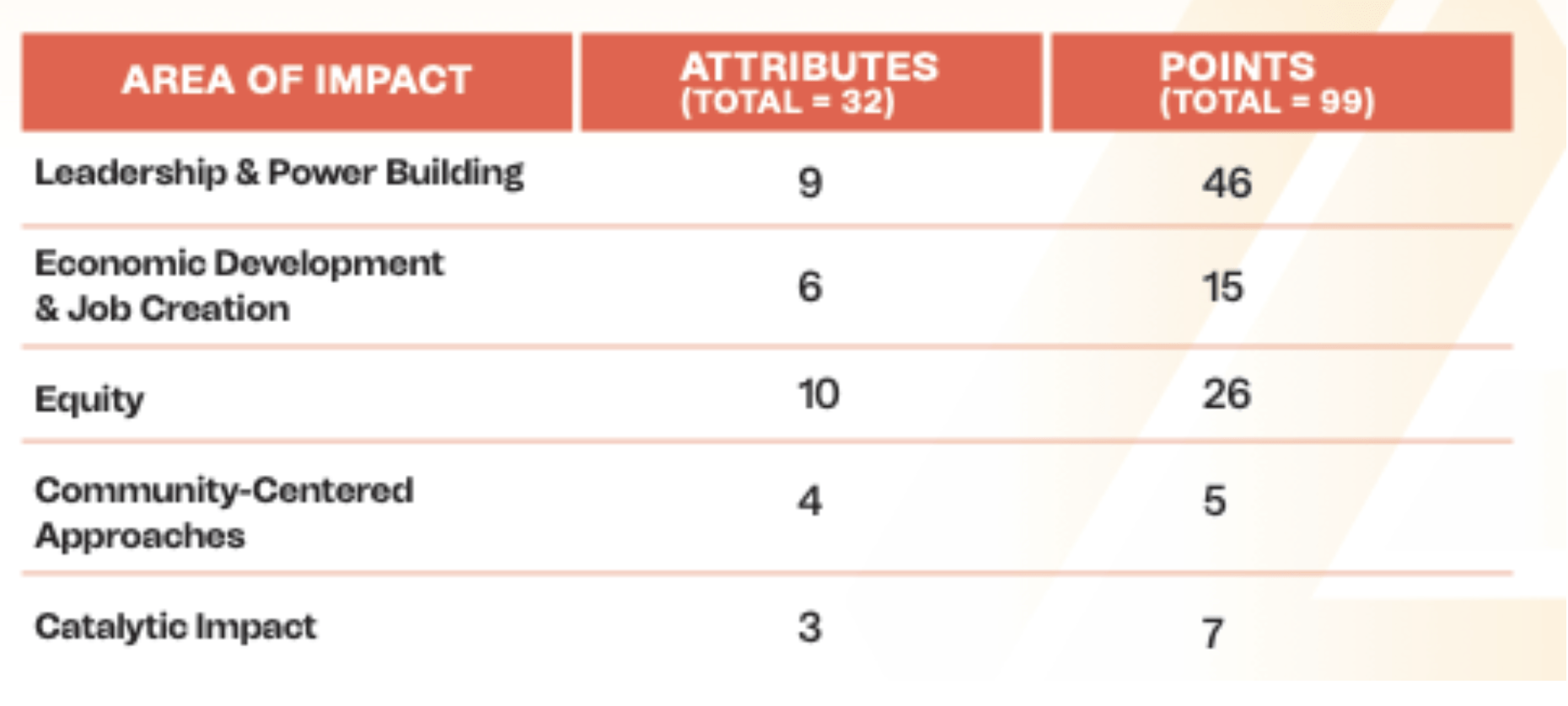

The result of those conversations was the initial scorecard, organized into five key areas. These categories, which were shared with NPQ and paraphrased here, are the following:

- Leadership & Power Building: Are leaders creating a path toward equitable policies and practices within the Black community?

- Economic Development & Job Creation: Are nonprofits, cooperatives, and businesses working toward a living wage, basic benefits, career-building, wealth-building opportunities and/or a fair and engaging workplace?

- Equity: Are projects proactively addressing historical and current systemic oppression in order to ensure fairness in the access to opportunities, resources, and rights for the Black community?

- Community-Centered Approaches: Are community partnerships trusted, held with confidence within the community, and based on the stated needs/wants of the community?

- Catalytic Impact: Will this support move a lender and project through a critical juncture, toward stated objectives or a critical decision?

Each category is subdivided into multiple questions. A summary of the questionnaire and the scoring matrix is below:

Together, the two groups developed a “scorecard” designed to encourage more CDFI creativity by making racial justice part of the due diligence process of loan evaluation and approval. Called the African American Equity Impact Scorecard, the effort aims to hold community lenders accountable to Black communities.

In August, I interviewed two Community Vision staff and two Alliance members to understand the scorecard development process, the obstacles they faced, and their vision for setting new industry standards going forward.

Developing the Partnership

According to Howard, the scorecard was initially prompted by a small grant program launched in the wake of the uprisings that followed the murder of George Floyd. “We were putting together a small grantmaking fund called the Black Liberation Initiative to recognize the urgency of investing in Black leadership and Black power building. That was specific to our work here in Central and Northern California. As part of that work, we wanted to create metrics.” But Howard added that her CDFI quickly recognized that the metrics were really “applicable across our organization.” Her team was also aware that the metrics could apply industry-wide.

“We felt as a White-led organization [we] could do better and could do more,” Howard noted. “And we felt that was the case for a lot of CDFIs and impact investors and banks and investors in general. At that point, we said it would be really interesting to have something like this that others, not just our organization, could use to [look] at their work through this lens and then hold accountability to Black communities.” At the same time, Community Vision felt it was poorly positioned to lead the charge on racial justice metrics meant to encourage investment in Black leadership and power building. This led the CDFI to reach out to the Alliance.

As Long explained, the Alliance is a fairly new organization of Black-led CDFIs. The idea for the organization dates back to 2018, but it was incorporated as a nonprofit in 2020. Long himself came on as CEO in 2021. At present, the association consists of 76 CDFI members. Combined member CDFIs have total assets of about $4 billion. Three large member CDFIs (with assets in the hundreds of millions) skew the average; the median member-CDFI has less than $30 million in assets. This is a sliver of the CDFI movement, which, according to the US SIF (Sustainable Investment Forum), had $457.9 billion in assets in 2022. This, as Long noted, speaks to large racial disparities within the CDFI movement. At the same time, the creation of an association of Black-led CDFIs offers the hope that through advocacy Black-led CDFIs can grow in stature and impact.

Long said when Community Vision approached the Alliance, his team was enthusiastic. “It is not often a White-led organization would have empathy and passion to want to address equity in a way that measures impact in the Black community,” Long noted.

“One of the most powerful things about the scorecard weighting is that it ensures that investments stay in Black hands the entire way through.”Devising the five categories was relatively straightforward. Howard elaborated the rationale behind each: The community-centered category was created because “we have seen so many CDFIs and impact investors that really do it [from] on high…We felt that was an important first step.” Equity, she added, “seemed pretty straightforward; that is one of the tenets of how we get to an equitable and just society.” Leadership and power building was developed to ensure that the “Black community would direct the development.” Economic development spoke to the need to assess whether projects are likely to deliver on their job generation promises. As for catalytic impact, Howard said, the goal was to place value on using capital in a way that others couldn’t and would drive the work forward.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Figuring out the weighting or points given for each of the five categories has been more complicated. That said, the weights were designed to spur CDFI activity where CDFIs were coming up short by increasing the points assigned to those categories, and lowering the points in the categories where the design team felt CDFIs were already doing a good job. As Sangokoya noted, “What we found in our pilot was that community-centered approaches and catalytic impact were receiving the highest scores….The areas where we continue to struggle with as an industry is how do we intentionally close the racial wealth gap.” She continued, “We really need focus more on equity, and leadership development and power building, and economic development and job creation.” As a result, these became the three most heavily weighted categories.

Keeper added, “One of the most powerful things about the scorecard weighting is that it ensures that investments stay in Black hands the entire way through. It really highly weights whether the organization is led by Black leaders; it highly weights whether those investments are going to Black-owned properties and whether those investments are staying in Black families for three generations. And whether those organizations are choosing to work with Black vendors and suppliers and…support Black beneficiaries.”

Howard concurred: “If we are not investing in leadership and power building, we are once again investing in a Band-Aid approach. We are trying to create a scorecard that says we are not just thinking about a charity approach; we are really thinking about justice and equity. If we are not investing in leadership and power building, there is no way forward there.”

For his part, Long noted that “the scoring metrics are intended to be disruptive and not to be standard….We have to be uncomfortable [if we are going to] move and address some of the things that we have been very uncomfortable in doing.”

Moving toward Implementation

In a pilot phase launched in 2022, 16 CDFIs participated. For this year’s launch, 12 CDFIs are participating. Over 100 loans have been scored to date. As a percentage of the industry, this number is tiny, but it is a big enough sample to identify the complexities of the new standards being developed—and thereby ensure that the tool achieves the racial justice vision of its creators.

Among those participating in the pilot, in addition to Community Vision, are Pacific Community Ventures (also in Northern California), Harlem Entrepreneurial Fund, Chicago Community Loan Fund, Albany Community Together (based in Georgia), AmPac Business Capital (based in Southern California), BiG Austin (based in Texas), Neighborhood Housing Services of South Florida, New Corp Inc. (based in New Orleans) and the CLIMB Fund (based in South Carolina).

Sangokoya noted that in the pilot phase, the focus was to “make sure the criteria to use the tool made operational sense and [was] in alignment with their racial equity goals.” Even though the scorecard has launched, refinement continues with the 12 participating CDFIs meeting monthly.

A key goal, Sangokoya added, is “to contextualize what ‘good’ looks like.” This involves standardizing scoring across organizations. As Sangokoya explained, “There might be some subjectivity [in the criteria]. We are trying to drive that out as much as possible and make the scorecard as objective as possible.”

Keeper explained that in the “last couple of sessions, we have had different users present a recent scorecard they put through, and they walk the group through it. And then we have a conversation [about] why they chose to score in a certain way and how it worked for that particular user. What challenges they may have faced in getting accurate data? What successes have come from scoring the project or using the scorecard in general?”

These discussions, according to Keeper, “have been the most generative and rich and important conversations that are driving the criteria of the scorecard, the way they are using it, and the way that we are talking about it.”

“The burden should not just rest just with the CDFI industry….The financial sector, banks, and foundations…how can they be held accountable?”

Building for the Future

While the racial equity scorecard has officially launched, these remain early days. Going forward, the two groups identified a few key priorities. One is to expand the network of institutions that are using the scorecard to guide their lending and investment decisions. After all, 12 CDFIs are but a fraction of a sector that numbers over 1,000 institutions nationwide.

As Sangokoya put it, “There are a lot of people who are circling and interested, but we still really want to share a call to action to join. People are creeping close. There are various barriers of getting their organization to register for a user account on the portal and start submitting the data on the portal. There is something big there that we are still working on.” Ultimately, Sangokoya added, the objective is for the scorecard to become the new industry standard.

Another goal is to challenge notions of risk. Sangokoya noted that the Chicago Community Loan Fund—one of the 12 CDFIs presently using the scorecard—when comparing the performance of “high-risk” projects with allegedly lower-risk projects that are the ones typically approved is “not seeing a difference in their ability to pay back.”

Long added that the onus to use the racial equity scorecard ultimately should extend beyond CDFIs. “The burden should not just rest just with the CDFI industry to make it happen. The financial sector, banks, and foundations…how can they be held accountable?”

Long concluded, “If this effort is really meaningful, and people really want to look in the mirror, I think that’s a challenge…not only [for] CDFIs to look at the scorecard but [also for other] financial institutions.”