July 12, 2017; Artsy

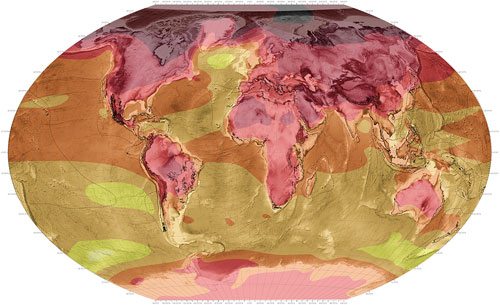

A team of academics has created an online project called “Atlas for the End of the World,” a collection of maps and graphics to help viewers see where and how urbanization is in conflict with biodiversity. It is “an atlas for the Anthropocene—the era of geological time shaped by the existence of human beings.”

Its creator, Richard J. Weller, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, said that while the project is “an aesthetic object in its own right,” it is “inherently fact- and research-driven.”

The atlas charts “hotspots,” 422 cities threatening 36 biodiverse areas. “Conflict maps” depict ever-expanding cities like Dongguan, China, which is “on a collision course with their natural landscapes.” Datascapes play out certain conditions to their extreme to show the environmental toll of a population of 10 billion people, the number projected for 2100.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Weller said, “We mapped that interface between urban growth and the world’s most valuable diversity…That conflict is bloody, it’s disastrous, it’s happening all over the world.”

Though the title sounds apocalyptic, it hints that the project is an answer to Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World), printed in 1570 and thought to be the first modern atlas. This collection of 53 maps summarized 16th century cartography. In a recent Artsy article on the project, Isaac Kaplan described the world in that atlas as “a place in which nature seemed to be an inexhaustible and unknown resource.” The end of the world being referenced is that world depicted by Ortelius at a time considered the beginning of modernity.

While the data is stark, Weller hopes that by “mapping the intricacies of ecological conflict…architects, designers, and others can help create more ecologically sustainable relations between people and the planet.” The denial of climate change is one part of the problem. Another is “the problem of visualizing the crisis itself.”

Weller said, “The poetics are not lodged in each drawing; the poetics exist in the overarching project of the atlas.”—Cyndi Suarez