July 15, 2019; Stateline

So far in 2019, the state of Oklahoma has won $350 million in settlements from drug makers Purdue Pharma and Teva for their role in exacerbating the opioid problem there; still to be decided is a case against Johnson & Johnson, where closing arguments were made on Monday. Now, the fight moves to what that money is to be spent on, and who controls it. Those vying for control of the money in Oklahoma include the attorney general and a group including the governor, lawmakers and local governments. Similar contests will surely play out in other states.

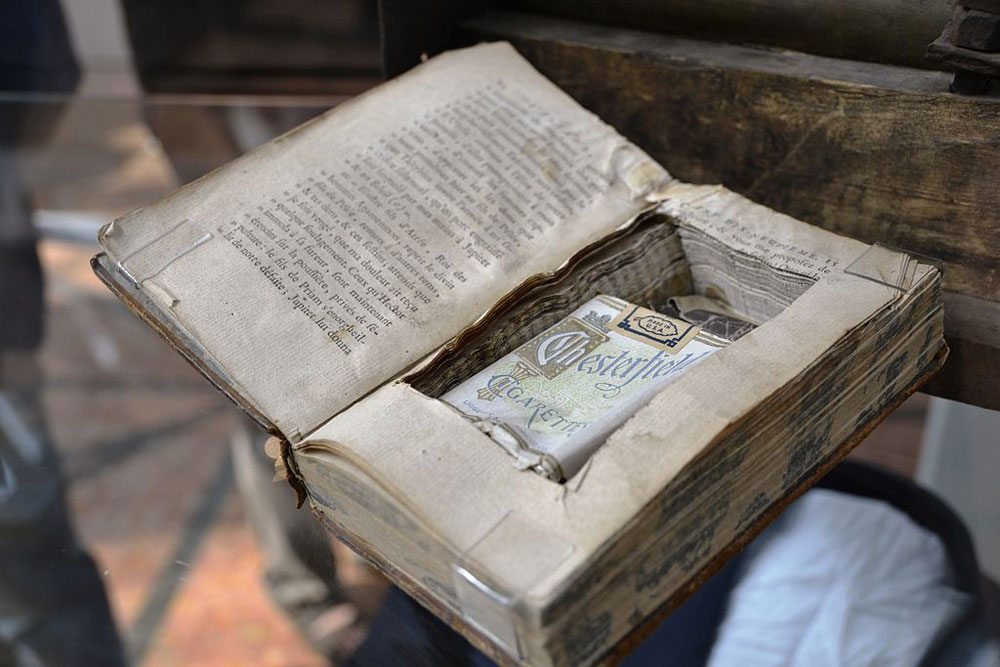

There is, of course, a set of unhappy precedents for the situation in the settlements reached 20 years ago with tobacco companies. Many lessons from that involve what not to do, as much of that money was never used to address the specific public health crisis on which the suits were based. Advocates fear a repeat unless decision-making is based on a clear set of principles and priorities.

“The lesson from the tobacco settlements is that unless the state attorneys general structure the settlements in a way that mandates the money be spent to address the opioid problem, it won’t happen,” warns Matthew Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. According to this article from Pew Trusts’ Stateline:

Under a 1998 master settlement between four tobacco companies and 46 states and the District of Columbia, states are receiving an estimated $246 billion over the 25 years of the settlement. The settlement stipulated that the money be used to prevent people from smoking and to help those already addicted to cigarettes quit.

Nineteen years later, states had spent only 2.6 percent of their total tobacco-generated revenue on smoking prevention and cessation programs, according to a Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids report last year, which concluded that most states failed to use the money as promised.

There will similarly be billions in play as a result of the cases now wending their ways through the nation’s courts for the opioid crisis.

“The reality is that you have two competing interests. Legislatures don’t want anyone to tell them how to spend money,” Myers says. “Yet attorneys general brought these cases for the explicit purpose of recovering money to address the opioid problem, not just punishing the companies.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A nationally consolidated class action lawsuit known as the National Prescription Opiate Litigation is scheduled to go to trial this fall in a federal court in Cleveland, and negotiations have long since been in progress to develop a national blueprint on how that money will be spent. A blog post by Joe Rice, lead attorney for plaintiffs in the consolidated case, says the current plan would allocate settlements “to local and county governments based on three factors: the volume of opioid painkillers sold in the state, the number of people who died from an overdose and the number of people who reported they had an addiction to the pills.”

Still, Myers says that doesn’t go far enough because “no strong citizen group is serving as a watchdog to ensure the settlement money isn’t used to fill potholes, lower taxes, build golf courses—you name it.”

“If that money goes into the general coffers,” Myers says, “Politics 101 guarantees that at some point—probably quickly—that money will be diverted. Sadly, if the money doesn’t get used to address the problem, it lets the wrongdoers off the hook. People will keep using these pills and keep getting addicted, and it will be business as usual for the drug companies.”

Making matters worse are the judgements often made about drug users.

Former West Virginia Attorney General Darrell McGraw, the Democrat who negotiated the nation’s first state settlement with Purdue in 2004 for $10 million, said in an interview with Stateline that a bias against drug users among the general public can get in the way of spending opioid settlement dollars to help people with an addiction.

Lawmakers tend to listen to their constituents, who often argue that any windfall from such a class action lawsuit should go to improve the community that suffered, McGraw said. “That, of course, opens the door for the legislature appropriating the money for a Fourth of July celebration or something.”

This article points out that even the federal government wants a portion of Oklahoma’s settlement proceeds, asking in a June letter to state officials how much Medicaid money has been used to pay for addiction treatment.—Ruth McCambridge