January 9, 2019; Colorlines

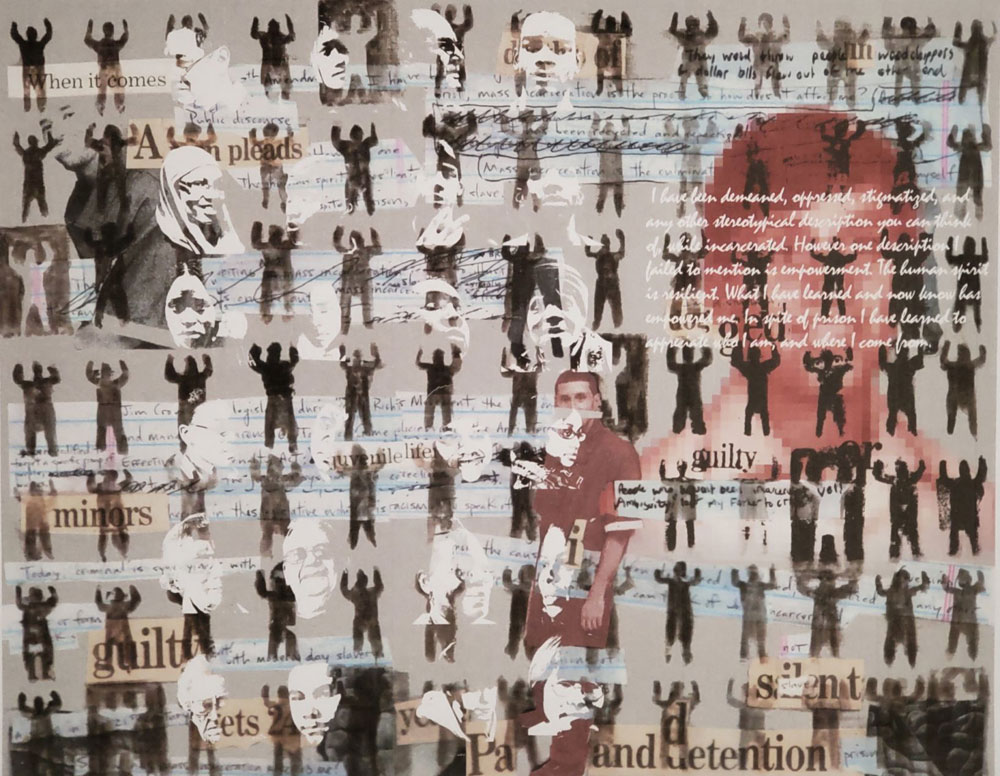

At the age of 17, James “Yaya” Hough of Pittsburgh was convicted of murder and given a mandatory life sentence in prison, with no hope of parole. This month—after 27 years of incarceration, which ended last summer—45-year-old Hough began a nine-month stint as artist-in-residence with the district attorney’s office in Philadelphia. As reported in Colorlines, this residency is the result of a partnership between Mural Arts Philadelphia (MAP) and the nonprofit network Fair and Just Prosecution (FJP), made possible with support from the Art for Justice Fund.

FJP works with newly elected prosecutors—including district attorneys—to change the criminal justice system and promote “fairness, equity, compassion, and fiscal responsibility.” Current Philadelphia DA Lawrence Krasner has been in office for two years.

Hough, in addition to being the first-ever artist-in-residence with a Philadelphia government office, is also believed to be the first artist-in-residence in any DA office in the country, according to an article in Philadelphia Magazine. That article, which includes an insightful interview with Hough, also explains why the artist is no longer in prison—because “the US Supreme Court ruled that the practice of sentencing juveniles to mandatory life sentences without parole—one that is unique to the United States—was unconstitutional.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

MAP is an internationally recognized, city-sponsored public art program with a long history of work in the field of restorative justice. Art projects—most often murals—are at the core of the organization’s efforts to build bridges between incarcerated individuals, victims and their families, and members of the broader community. MAP often works with those who are incarcerated and has a number of initiatives aimed at work-readiness for returning citizens and vulnerable young people. Because most of the organization’s murals are created on fabric (in sections) and then applied to walls, many incarcerated individuals participate in the art-making process, even though some of them will never see the completed public works once they are installed in the “outside” world.

Perhaps it is no surprise that Hough, who served time in two Pennsylvania state prisons in the Philadelphia region, got involved with MAP back in 2006. In fact, before his residency even began, he’d already had a hand (or two) in 50 murals created for MAP projects around the city. As described on the MAP website, Hough’s 2020 residency “will culminate with works of public art that explore the human toll of incarceration and highlight the importance of creating alternatives to a punitive and incarceration-driven justice system—offering the public and members of the District Attorney’s Office (DAO) a chance to engage in direct dialogue on criminal justice reform issues.”

Hough believes his life experience makes him well-suited for his new role: “They were well aware of artistically what I was capable of, but also on another level, my commitment to these types of issues. I’m able to present a certain balance that most artists probably can’t because they don’t have the lived experience.” His bio on the MAP website notes that in addition to his residency in Philadelphia, and his art-making back in Pittsburgh, Hough is also active with the nonprofits Decarcerate PA! and Project LifeLines and “seeks to be part of changing the prison system in Pennsylvania and abolishing Life Without Parole.”—Eileen Cunniffe