Barcelona is often celebrated worldwide as a leading site of municipalism, an approach that combines a politics of liberation with a pragmatic, problem-solving focus. As the New Yorker’s Masha Gessen detailed a few years ago, “Municipalist programs tend to be focused on the specific needs of a city’s residents and specific programs that address them.”

These days, activists from all corners come to Barcelona to learn how community-run associations have put a solidarity economy into action—promoting local democracy, community education, and wellbeing. Many of those inspired by Barcelona’s example have adopted similar strategies in their own communities.

However, the situation was once quite different. From 1939 to 1975, Spain was ruled by a fascist government led by General Francisco Franco. Nou Barris, the nine neighborhoods at the heart of this movement, were predominantly immigrant and working-class. In 1976, a cement factory opened. It was supposed to be an economic boon, but it became evident that the plant was poisoning the community.

Working quickly, residents…called together a community assembly to declare in unison that this factory was being reclaimed by the people.

A year later, a community uprising took place. The polluting factory was converted into a community-run institution, known as the Ateneu Popular de Nou Barris (Cultural Association of the Nine Neighborhoods), which became a driving force behind local victories ranging from paved roads and environmental protections to improved public transportation and community health—and inspired many imitators.

Although local in nature, this history has implications for movement activists in communities across the globe. It shows how movements from modest origins that tap into community history can materially benefit the lives of thousands of people.

Save Our Lungs!

When the factory began operating in 1976, it was supposed to create needed jobs for the community. But once it opened, residents quickly noticed that when they hung clothes up to dry outside, they quickly shriveled due to dust from the plant. Children developed breathing problems as they inhaled the poisonous air. Public health problems spiked.

As the health crisis worsened and city officials failed to act, residents decided to take matters into their own hands. On a cold and clear January morning in 1977, a delegation of neighbors equipped with rope, hammers, and shovels marched to the plant carrying a banner that read: “¡Salvemos nuestros pulmones!” (“Save Our Lungs!”). Taking advantage of protests across town which had occupied the police, the protestors began physically dismantling the polluting machinery inside the factory.

Working quickly, residents then called together a community assembly to declare in unison that this factory was being reclaimed by the people. From now on, it was decided, the building would serve to heal the community rather than poison it.

So popular was their action that, despite millions of dollars in damage to the property, the mayor did not try to press charges against those involved, preferring, as one local newspaper put it, to avoid conflict and live “an easy life.”

In the months that followed, the people transformed the factory from an empty toxic shell into a vibrant space of cultural life. They brought in music, theater, poetry, debates, and a community circus. When a grand opening was held three months after the initial occupation, thousands attended. Together they christened this space Ateneu Popular 9 Barris—in honor of the nine neighborhoods that it represented.

A Labor Heritage

The title ateneu paid homage to the widespread ateneus populares or “people’s athenaeums” of the 19th and early 20th centuries. These were community-run associations, mainly found in northern Spain, and dedicated to the advancement of learning for everyday people. Much like the citizenship schools built by civil rights organizers in the US South, ateneus taught reading and writing, politics, literature, history, and science to anyone who wanted to learn.

In a time when formal education was still largely reserved for an elite intelligentsia, these “democracy schools” not only made basic education available to the most marginalized but also taught people how to take action on the issues affecting their community. As one local magazine described: the culture of the ateneu “should entertain, but also explain why things are as they are, discuss them, and foster the necessary responses.”

The campaign…did more than shut down a polluting factory. By recreating the community hub…residents resurrected old community traditions.

Participating in these ateneus helped neighbors from different backgrounds build relationships. In so doing, they learned that their families faced common issues and helped them to identify tools to address those issues. The ateneus married popular education and neighborhood identity to create powerful vehicles for local change and personal development.

Because all community members could take part in these ateneus, the children that grew up in these institutions often became the next generation of civic leaders. Labor leaders like Teresa Claramunt first learned the skills of organizing, writing, and public speaking in the neighborhood ateneu. Claramunt put those skills to use building one of Spain’s first feminist unions and leading the strike that won an eight-hour workday for laborers.

By the early 20th century, ateneus could be found in nearly every neighborhood throughout Catalonia until the consolidation of the Franco regime put an end to these institutions.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Rebirth

The campaign in the winter of 1977 did more than shut down a polluting factory. By recreating the community hub of the ateneu, residents resurrected old community traditions, albeit ones interrupted by nearly 40 years of dictatorship. The Ateneu Popular 9 Barris helped develop a new generation of democracy schools.

Campaigns that have come out of the ateneu have had a broad range. Often the issues are hyperlocal: paved roads for the neighborhood, improved public transportation, street lighting, and more. Residents also fought against gentrification and pollution, ultimately winning environmental protection policies for the surrounding mountain landscape.

The community…is [unified] by five values: respect, solidarity, cooperation, mutual support, and participatory democracy.

In response to Spain’s heroin epidemic of the 1980s, the community used the ateneu to open a youth center—launching a series of juggling, stilt-walking, trapeze, and other workshops to keep young adults off the streets while celebrating the cultural heritage of the circus in Catalonia.

The ateneu, in short, served as a community hub where people met, where community issues were debated and plans made, where trainings were held, and alliances formed.

But political work was (and is) just a portion of the activity in Ateneu Popular 9 Barris. In addition to serving as a platform for community organizing, the space brought life back into the neighborhood. Groups were formed to reinstate carnivals and launch new festivals such as La Cultura Va de Festa (The Culture Goes Partying) which hosts hundreds of visitors each year. The inseparable relationship between this political and social work is perfectly captured in the ateneu’s motto: “Action, Struggle and Fun.”

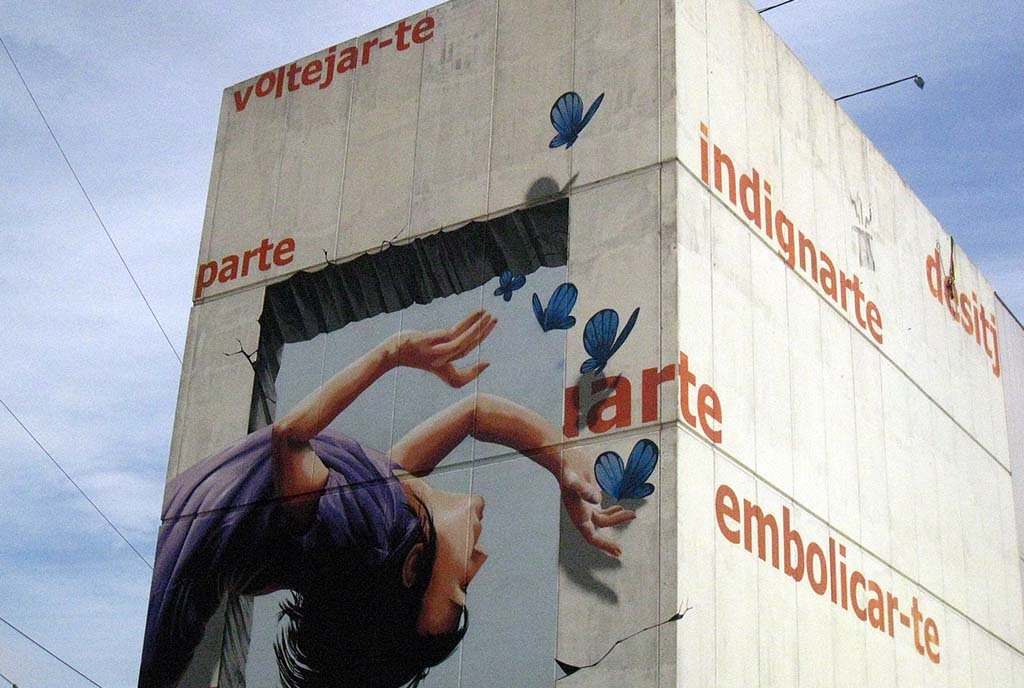

Building a Culture That Teaches Democracy

Today, the neighborhood of Nou Barris has been transformed because of its ateneu, and other communities across Barcelona have taken note. Many have rebuilt ateneus of their own. Some have used refurbished old factory buildings, others have negotiated to gain ownership of historic neighborhood houses. There is, once again, a thriving culture of local democracy being woven in the streets.

In an era when many of the community institutions elsewhere are in decline, the stories of Barcelona’s ateneus have valuable lessons to teach. The social importance of such community institutions is clear: whether it’s a union hall, church, or school, these spaces tie people together across differences with a common set of values.

The community of Nou Barris is not unified by race, income, political party, or even language but rather by five common values: respect, solidarity, cooperation, mutual support, and participatory democracy. These, they have agreed, are the basis of a community that creates a fair and equitable society.

The political lessons are equally important: these community-based institutions are the most potent vehicles people have for developing local democratic power. They are one of the few places where everyday people can build a constituency large enough to impact the real-world issues that affect them and their families. As community leaders in Nou Barris say: “Better to do it together than alone.”

But above all else, members of Ateneu Popular 9 Barris stress that the most important part of their work is cultural. Their mission is to build a culture that perpetually teaches the values and practices that individuals need to live in community and democracy.

In this sense, political and social work are merely tools to help people develop the values that enable them to take responsibility for the wellbeing of each other and the planet. Through artistic and educational activity, these shared values and codes are cultivated; through debates, public assemblies, and theater, ateneus strive to teach critical thinking “to counteract manipulation of racist and patriarchal speech”; through their community-managed structure, ateneus are a school of democratic participation and social organization.

With growing polarization when people feel unheard by their political representatives and powerless to provide a better life for their children, the ateneu teaches that real change and social transformation is possible through this culture of collective work.

When describing what made the remarkable legacy of Ateneu Popular 9 Barris possible, one of the residents simply said, “It’s because people have power here.”

“That is crucial,” she continued, “because we know what it is like to have no power at all. Under Franco, people—and especially Catalans—had no choice but to do what they were told. We will never give up our freedom again, and the only way we can maintain it is if we stand together.”