In Tuesday’s presidential mêlée—calling it a debate would be journalistic malpractice—Chris Wallace, the ostensibly objective moderator, introduced a question about the economy with a comment that “The economy is, I think it’s fair to say, recovering faster than expected from the shutdown.”

To be fair, Wallace’s question sought to get candidate responses as to whether the nation faced a K- or V-shaped recovery. This is a topic we’ve addressed at NPQ before. But it is not really a question. There are data here, and they are stark and frightening.

Unfortunately, Wallace’s cluelessness in framing this question—and at such a critical venue as the “debate”—seems to be shared by many in power, including Congress, which has failed to pass relief legislation, and the Democratic Party, with both presidential candidate Joe Biden and vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris remaining largely silent on the nation’s continued unemployment crisis. The nonprofit sector has not covered themselves in glory on this issue either, failing to address this foundational issue as structural and generative of a full host of social, health-related, and environmental problems for the American people.

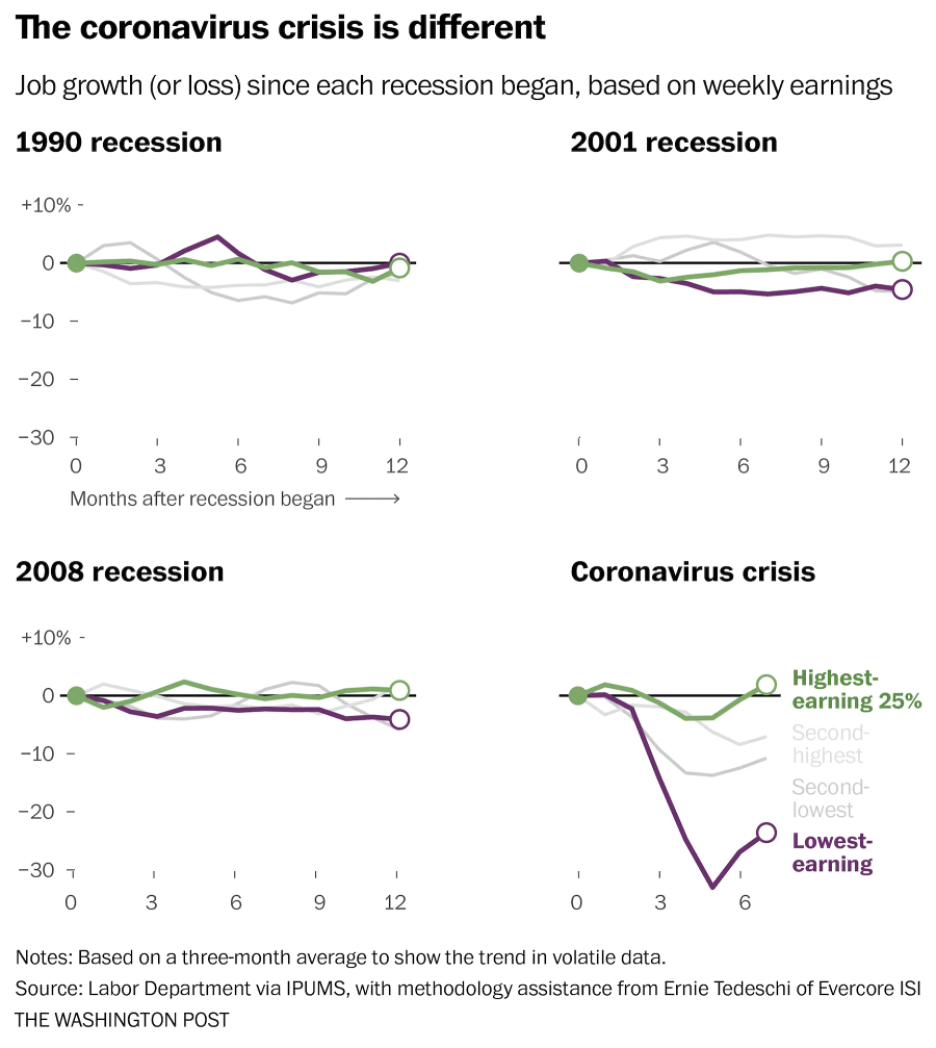

So, let’s focus for a minute on the real picture of this so-called recovery by drawing your attention to a set of graphs tracing the effects of this recession on various strata of the economy. We are grateful to the Washington Post for this information, presented in a simple, stark form.

The graph above comes from an article written by Heather Long, Andrew Van Dam, Alyssa Fowers, and Leslie Shapiro at the Washington Post—based on a monthly survey of 60,000 households conducted by the US Census Bureau on behalf of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Six months after the downturn, the Post finds that at least 15 percent of those in the poorest half of households employed six months ago still lack a job today. By contrast, Great Recession job loss never exceeded 10 percent. And yet, for those in the top 25 percent, jobs today exceed those at the start of the pandemic.

For the uninitiated, a K-shaped recovery means recovery for some (the upward leg of the K) and continued misery for the rest (the downward leg of the K). Well, as the Post charts show, while downturns have had differential effects by race and class before, those effects utterly pale in comparison to what we face today.

Welcome to our K-shaped recovery on steroids!

The class divide is the most obvious dividing line, but it is not the only one. Here are some of the many ways, beyond class, that the COVID-19 downturn has worsened and deepened pre-existing economic inequality.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Race: White Americans have recovered more than half of lost pandemic jobs; Black Americans just over a third. Latinx Americans, reports the Post, “saw the steepest initial employment losses and still have the most ground to make up to reach pre-pandemic employment.” Among women, white women “have recovered 61 percent of the jobs they lost—the most of any demographic group—while Black women have recovered only 34 percent, according to Labor Department data through August.”

- Gender: “Mothers of children ages six to 17 saw employment fall by about a third more than fathers of children the same age, and mothers are returning to work at a much slower rate.” Mothers of children ages six to 12—the elementary school years—have, the Post indicates, “recovered fewer than 45 percent of jobs lost, while employment of fathers of children the same age is 70 percent back.”

- Age: Americans ages 25 to 34 have recovered only 43 percent of their lost jobs, compared to nearly half for the population as a whole.

- Education: Workers with college degrees have recovered 55 percent of their jobs, compared with less than 40 percent for workers with high school degrees. People with college educations were also far less likely to face job loss in the first place. The Post points out that there were “as many as six-in-ten college-educated employees working from home at the outset of the crisis, compared with about one-in-seven who have only high school diplomas.”

Overall, the Post observes: “No other recession in modern history has so pummeled society’s most vulnerable. The Great Recession of 2008 and 2009 caused similar job losses across the income spectrum, as Wall Street bankers and other white-collar workers were handed pink slips alongside factory and restaurant workers.”

“It’s an even more unequal recession than usual,” concurs Ben Bernanke, who chaired the Federal Reserve during the Great Recession. Bernanke adds, “The sectors most deeply affected by COVID disproportionately employ women, [people of color], and lower-income workers.”

And a full and complete recovery is not expected for some time yet. Right now, the Federal Reserve is predicting that overall unemployment will not near pre-pandemic levels until the end of 2023.

Now, let’s go back to the proper role of nonprofits in all of this. The playbook usually says to eschew economic policy unless it specifically affects an organization’s mission. But at this point, inaction is a violation of fiduciary responsibility. If your mission is in health, education, childcare, community economic development, or social services—to name just a few leading areas of nonprofit activity—ask yourself just how your nonprofit could fail to be devastated by these stunning numbers. We know that poverty, along with systemic racism, places people at risk for all manner of health risks that regularly end in early mortality. The pandemic has definitively proved that once again.

Sadly, it falls to an economist to underscore the obvious. As Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, tells the Post, “There are very clear winners and losers here. The losers are just being completely crushed. If the winners fail to help bring the losers along, everyone will lose. Things feel like they are at a breaking point from a societal perspective.”

Preventing society from breaking? That would seem to be a key nonprofit raison d’être.

These are, to be sure, very scary times. And if we’re honest, finding the answers will require experimenting—and not everything tried will succeed. But some pieces of what we need are obvious. In the immediate term, that includes relief—unemployment insurance, money to keep people in homes, money to schools, money to states and localities, to name a few things. And then there is the need to shift the ownership of assets, so that the economy is never again so absurdly concentrated among a white elite few as it is today.

The unacknowledged reality is that many nonprofit leaders and board members are in that top quartile on that Washington Post graph. It is so easy to forget our fellow Americans. But our fellow Americans may not so easily forget what we did—or did not do—in our hour of greatest need.