June 30, 2014; Forbes

Should charitable contributions be tied to a metric system similar to the one often used to build baseball teams? Some observers want to see a mode of philanthropy based on the principles of “Moneyball,” a concept from Major League Baseball crafted and practiced most famously by Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics.

The concept of philanthropy and giving has been taking some interesting, at times odd turns lately. Back in the day we can remember people and companies making donations because, quite simply, it was the right thing to do and it made them feel good. They listened to a pitch made by a colleague, or by the leaders of a nonprofit organization, and they decided to give based on a trust in the people involved.

In recent years, however, that is not good enough for many philanthropists. The donations might be directed to achieve a result the donor wants, as in the theory of Strategic Philanthropy. Or, there is the idea of doing good through donations to build a brand and sell more product in Cause-Related Marketing.

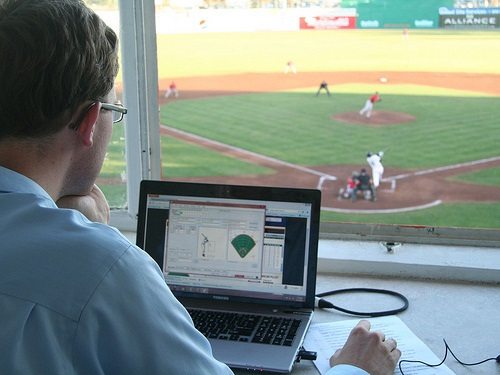

A new idea is being captured in a term called Moneyball Philanthropy. For those who are not as deeply into the game of baseball as this writer, Moneyball is the term used to describe a system of how to build a baseball team adopted initially by the Oakland Athletics. The Moneyball theory is that the hunches of scouts are not a really good guide to a player’s quality, but there are any number of statistical analyses that can be done that will give a munch better idea. So, build your team around the players with the best statistics, the theory goes.

So, too, with Moneyball Philanthropy. In the nonprofit world, the scouts are those people who are making the ask for a donation – don’t trust them. Instead, look to the statistics that will demonstrate that your donations are going to have a real impact on the issue and make real change. As one proponent of this approach, Cass Sunstein, the former administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. recently wrote, “what is most important is the movement, still in its earliest stages, toward rigorous evaluation of whether and how charities are actually helping people. With hundreds of billions of charitable dollars being given every year, it’s time for Charitable Moneyball.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

{loadmodule mod_banners,Ads for Advertisers 5}

A couple in Houston have been gaining notoriety by using a Moneyball Philanthropy approach as they decide how to give away their $4 billion. They have hired people to conduct rigorous research into effective methods to fight such things as childhood obesity and to improve the correctional system.

The Moneyball Philanthropy approach argues that donations should be made to organizations that are the most effective, and leaving all the others behind. It is based on a belief in empirical data showing that if a certain amount of money is invested, there will be a predictable and positive impact on a social ill. But, as some writers are pointing out, life isn’t always that simple. Baseball is played with very strict boundaries, rules, and systems. The results are predictable, and immediate. Life, in general, is not quite so neat and tidy, riddled with variables of human personality, politics, and other pressures that can change at a moments’ notice.

It is also being pointed out that some of the biggest, most impactful work being done by nonprofits is in the area of systemic change, a type of work that can take years to come to fruition, but when it does, it can change the world. Working on changing societal attitudes to same sex marriage, for example, has begun to show real results, and the potential benefit to our society will be very real, but may not be measurable.

Further than that, there are many causes that do not lend themselves to empirical measurement the way some social ills do such as the performing arts, for example, or leadership development. Both make our society a better place, but how do you measure the impact of a dance performance on the audience? The world needs new leaders, as we are continually told, but how do you measure the growth of leadership in an individual or that leader’s impact?

Finally, if empirical data and proven results are the basis for giving, where do the new and groundbreaking ideas go to get support? These new ideas may be the ones that cure cancer, but if they can’t prove it, they can’t get funded and they can’t prove it until they get funded.—Rob Meiskins