“A beauty of art is simultaneity—multiple truths being allowed to exist. What would happen if the world could live with that—multiple truths existing?”

—Sharon Bridgforth and Omi Jones

The Management Assistance Group (MAG) is one of NPQ’s go-to sources of information about social justice movements. MAG works with a number of the networks that are moving some of this nation’s most difficult issues. MAG has come to believe there are five elements that are critical to advancing a thriving justice ecosystem. This is the third in a special five-part series, in which MAG and NPQ invite you to contribute to the evolution of what these elements mean in practice. Let’s start something!

Have you ever had an encounter with the world—one that reaches right into your brain, your heart, and your gut and radically alters the way you think, feel, and act? This is the terrain of multiple ways of knowing.

There is a strong bias in the U.S. dominant culture, one that shows up in the nonprofit sector as well, to value only one way of knowing, the one grounded in data, analysis, logic, and theory—a rationalist’s approach to truth. But there are many different ways to understand and engage with the world. These other ways of knowing are equally meaningful, and are critical to our efforts to understand complexity and create the possibility for transformational social change.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described justice as moving “toward the public manifestation of love.” To publically manifest love, we must incorporate all our ways of knowing. Dr. King modeled this by bringing his own experience and faith, what he learned from the faith of others, his scholarship, and deep cultural traditions of music and song together with theory and action to advance a vision of love and justice.

A Framework for Understanding

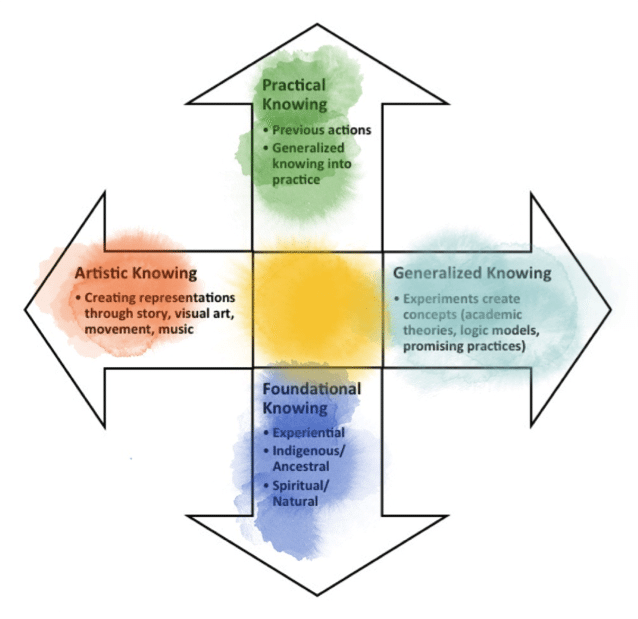

To help us grapple with the multitude of practices and embrace the many “ways of knowing”—and to bring greater clarity to the impact of integrating them into our social justice work—we began using extended epistemology, a theory developed by Peter Reason and John Heron. This theory categorizes four interdependent ways of knowing: experiential knowing, presentational knowing, propositional knowing, and practical knowing.

This theory has been useful in thinking about the wisdom that is critical to harness to effect meaningful social change. But there are other elements of knowing, such as what we learn from indigenous/ancestral wisdom and the natural world that we, along with our partners, clients, and people we interviewed for this article, have found important to lift up in more pronounced ways. As a result, we have developed on the framework to better understand and act in meaningful and interdependent ways in the world.

The framework, like extended epistemology, is rooted in four interdependent ways of knowing:

- Foundational Knowing: There at least three major foundations for how we make sense of the world: experience, indigenous/ancestral wisdom, and spiritual/natural wisdom.

- Artistic Knowing: To understand our experiences and to help others understand them, we create representations through story, visual art, movement, music, etc.

- Generalized Knowing: We look at patterns and experiment to create concepts. This is where academic theories and propositions live, as well as theories of change, logic models, and promising practices.

- Practical Knowing: We act intentionally in the world in ways that are informed by our previous actions, as well as our generalized knowing. We take our generalizations and turn them into practice.

Too often, we stay in generalized and practical knowing, rarely dipping into foundational knowing or artistic knowing in meaningful ways. By not intentionally drawing on these, our theories and action plans are often disconnected from our values and beliefs, and the bedrock experiences of our lives. Moreover, privileging one way of knowing over others (e.g., generalized knowing, with its focus on measurable data) marginalizes and ignores other truths that people bring from other ways of knowing. This marginalization often lies at the core of conflicts, systemic barriers to change, and inequity.

Foundational Knowing

Foundation knowing consists of at least three fundamental ways of making sense of the world: experiential, indigenous/ancestral, and spiritual/natural.

Experiential Knowing

For Pamela Standing, director of the Minnesota Indian Business Alliance, experiential knowing is a wisdom enacted in our way of being with others—a way that looks deeply within another person and takes the time to see what emerges, rather than reading another person based on what is immediately presented.

“We are interested in the core of what people are about, rather than their resume,” notes Standing. “Native people call experiential knowing ‘craft wisdom.’ It’s an ability that you carry. When I’m in a group with elderly people, I know that they may not have a formal education, but they have a PhD in life. You can’t learn that in a book and can’t learn it by going to college.”

But Standing finds this way of knowing radically undervalued in contexts with less Native presence. Recently, a partner was looking to convene a group of people and hoped for more Native attendees. “I told her that it would be hard to attract Native American people to an event if you have to have a college degree to be part of it. We don’t make choices based on that.”

Whenever possible, Standing tries to share different ways of knowing and being to encourage different approaches. She and people from the six Anishinaabe bands in Minnesota brought scientists together to help them understand the impact genetic modification of wild rice was having on a native food staple, one inextricably linked to their way of life. “We took them out rice harvesting [also called knocking the rice or ‘manoominikewin,’ a practice that Ojibwe people have been engaging in for centuries] so they could experience things differently. They were really moved.”

From this experience, the scientists began to understand the impact of genetic modification on diet, nutrition, and traditional food gathering rituals, as well as their practice of what Standing described as “going into tribal communities, just trampling all over the land and starting to take samples.” Sharing their native worldview and Anishinaabe lifeways, notes Standing, “deepened their respect.” And in turn, it created a collaborative opportunity for addressing an environmental, food systems, and indigenous rights issue to greater effect.

Indigenous, Ancestral Knowing

For Native peoples, such as the Ojibwe and Choctaw of the authors’ heritages, indigenous or ancestral wisdom is a language still spoken; its guidance is still heard. But ancestral wisdom exists across all cultures and peoples. Prior to the rise of the scientific revolution, ancestral wisdom was a critical aspect of experiencing and understanding the world. Such common European American proverbs taught to us by our elders, such as “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”—referenced in Hugh Rhodes’ The Boke of Nurture or Schoole of Good Maners, circa 1530 and most often interpreted as a means of encouraging us to recognize the value of what we have—have guided us for centuries. But our current overreliance on knowings born exclusively of Western scientific methodologies has lessened the value of ancestral knowledge and the impact it has in creating meaningful, community-based social change.

While in Hawaii working with a group of over 50 people from 10 different indigenous communities in North America and Hawaii, the importance of this way of knowing came to life before our eyes. We were gathered together to create ways to improve the educational experiences among youth in these communities from preschool through high school. The evening before our first full day, we came together for a cookout at the beach, playing games, cooking and swimming together—building relationships, extending our ‘ohana (in Hawaiian, “‘ohana” can mean family in a broad sense that includes blood relatives and adopted or intentional family).

The following morning, we did not jump immediately into current educational theories, test scores, or other sets of student or teacher data to learn about the educational challenges we each faced in our communities. Instead, we were first taken as a group to a place reserved for paying respect to ancestors. The Native Hawaiian host group led a prayer ceremony in front of native wood sculptures in which they welcomed their ancestors and asked them for permission to bring the rest of the group onto sacred land. Most of the group had tears in our eyes as we listened to the prayer and songs, spoken in a language few of us knew. We became vulnerable in front of each other, which enabled an instant knowing of the deep responsibility we carried to both the past and the future and to the children for whom we were imagining a better experience of public education. This knowing was named by almost everyone during the day’s debrief and it provided an undeniable current in the flow of our work for the rest of that week and beyond. We did not have to decide on centering this knowing as a priority to guide our work together; it was simply presenced by this ceremonial practice of honoring and engaging ancestors.

Another example of drawing on indigenous/ancestral wisdom in social justice work comes from a client and partner in the field, Ifetayo Cultural Arts Academy, which supports the creative, educational, and professional development of youth and families of African descent in Flatbush, Brooklyn, and the surrounding communities. Ifetayo honors the ancestors and elders through formal structures (e.g., the Council of Elders) and through practices and concepts drawn from African traditions. One of these is Mbongi, which translates as “a place of learning” and is a community space where all people have the power to raise and discuss questions, concerns, conflicts, and reflections. Mbongi is rooted in an ancestral knowing of how to resolve conflict and innovate. As described by Sandra Bowie, executive director of the Ifetayo Cultural Arts Academy,

Mbongi is a practical example of how youth are able to exert their perspectives alongside adults by “calling” the community together to address problem-solving and the community is obligated to respond. … Each person’s voice is valued and taken into consideration in an open, honest, and authentic way.”

Through Mbongi, Ifetayo is able to develop a comprehensive, systemic understanding of issues and can come to agreement about desired actions. It has helped Ifetayo to build a strong community, develop leaders who can engage in courageous conversations, and enhance all aspects of its work from programming to operations.

Spiritual/Natural Knowing

Our access to understanding is most often rooted in simile and metaphor, in the imaginative capacity of language. We understand the movement of blood in our veins and arteries through descriptions of rivers and their tributaries. We describe complex social systems through their natural corollaries: trees and their interconnected root systems, wetlands and the delicate interdependence of their plant and animal species. We understand our own connection to the earth and its sentient tapestry through the increasingly evident impact of our destructive behaviors on every living thing around us: the land, sky, waters, and glacial mountain peaks. And, through the impact on our environment, we are beginning to understand the impact on ourselves.

Spiritual beliefs and practices throughout the world are also rooted in an understanding that there is something larger than us. For those who resonate more with an agnostic or atheist belief system, justice itself becomes sacred. Pamela Standing says, “We always begin with a prayer. If we are working with communities, what we are doing is sacred.”

To prepare herself for such sacred work, Standing invites spiritual help each day, asking “to have what I need to live in a good way…to remember what is it that I am putting my hands to today.” And, too, to do so with reverence and care. Without this, she says, we are missing the help that is available to us. “There is something bigger than us that we need to listen to” and whose support we can draw on and from.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Artistic Knowing

“Poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.”– Audre Lorde, from the essay “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” first delivered in an address at Mount Holyoke College in 1978.

We create representations of our experiences through story, visual art, movement, music, etc. in order to understand them as well as to help others understand them. These different ways of knowing lead not only to fuller knowledge of self and others; they also lead to alternate perceptions, apprehensions of the truth, and ideas and actions for addressing our shared challenges.

Artistic Knowing Leads to Different Results

Thousand Currents (formerly International Development Exchange, or IDEX) partners with funders and donors to provide flexible small grants to effective, locally-based organizations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America led by women, youth, and indigenous leaders. In the summer of 2015, Thousand Currents began an artists-in-residence program with Sharon Bridgforth and Omi Osun Joni L. Jones, who offered theatrical jazz as a tool for improvisation, creativity, and innovation. They brought together the staff, guiding them through creative processes.

Through her work in organizations, Sharon Bridgforth sees people creating “experiences of love by being together…relinquishing some aspect of identity in order to find it.” They are, in fact, building community and in the process also accessing the “freedom to have their own experience,” she says, “allowing there to be many truths.”

Bridgforth notes that “recognizing our humanity…is a necessary condition of leadership and working with whole people in this way creates the necessary humility in folks. We introduce people more deeply to each other so that they can work together differently. What’s different [is that] when we are whole people doing this work, we are fully present with everything we’ve got. We cannot be present and be hiding at the same time. Hiding and presence are not simultaneous truths.” And it is only when we come to social change with our whole presence that we can heal and transform our world.

Bringing creative and cultural-based strategies for team and organizational development led to unexpected but welcome outcomes. The staff believes that the forms and practices they engaged in together, which included creative writing, music, and movement, enabled them to learn a lot about vulnerability, courage, accompaniment, and joy. Staff shared,

Raising resources is not easy. Building alliances and deepening relationships takes time. At the same time, they are all sources of joy. If we emphasize on the joy, we will move forward and more creatively with our work, shedding the martyrdom sometimes inherent in our nonprofits. We committed and recommitted to great joy in all we do, as a tribute to our partners, our ancestors, and to our collective strength.

Thus, they see an increase in their vulnerability and a deeper awareness of their own humanity, which is critical to how they approach their work.

Rajiv Khanna, Director of Philanthropic Partnerships at Thousand Currents, and the executive director of Thousand Currents, Rajasvini Bhansali, herself a longtime poet and former member of poet activist June Jordan’s Poetry for the People, agree that there has been a difference in how they do their work. In addition to the greater self-knowledge and knowledge of one other, the process has grown Thousand Currents’ leadership and team capacity as well. The organization has begun embracing cultural (indigenous/ancestral) and artistic ways of knowing alongside—or even instead of— those rooted in U.S. dominant culture. This shift has caused Thousand Currents to dramatically change its strategy, shift its theory of change, and re-envision how it goes about its work of advancing change in the world.

Reclaiming and Sharing Our Multiple Ways of Knowing

Like Bhansali, both authors have a long-standing creative practice and in fact met in a jazz poetry class many years ago. Despite our longstanding artistic practice, we found ourselves creating separations between our artistic pursuits and our leadership development work in U.S.-based nonprofits. Somewhere along the way, we had come to accept the dominant Western idea that art lived in one house and theories of change, logic models, and principles of leadership lived in another.

The limitations of this separation became pronounced as one of the authors began reclaiming her artistic knowing by bringing creative writing and media arts to youth as a leadership development methodology. This led to an exploration of what it means to bring what Brian Hall termed “ritual communication” into leadership development work. Hall roughly defined ritual communication as skill with and use of ritual, archetypal symbols and the arts as a communication medium for making meaning and for raising critical consciousness of complex issues or the awareness of the transcendent. From his decades of work with individuals and organizations, he viewed this as an essential part of education, learning and the learning organization.

We have increasingly seen the presencing of ritual to facilitate meaning-making and healing in a number of social justice spaces. While this is a long-standing practice for indigenous communities and communities of color, it was mainly something shared only within one’s own community. Over the last few years, broad coalitions of social justice actors have come together in order to address complex social justice issues, and in so doing have opened up space for sharing our multiple realities and experiential truths so that we might move forward together. To illustrate this shift, Dignity and Power Now (a Los Angeles-based criminal justice reform organization and network) has a Director of Health & Wellness who leads their “building resilience” work. Another Los Angeles organization, the Youth Justice Coalition, engages in a combination of rituals—such as altar-building and mural creation—that honors young people of color lost to violence. These rituals are rooted in African and Indigenous American traditions and draw on the support of our ancestors in order to increase community cooperation and engender mutual abundance.

Generalized Knowing

More deeply presencing foundational and artistic ways of knowing does not lessen the value of generalized and practical knowing. Generalized knowing is drawn from patterns and repeat experiments. It includes concepts, theories, logic models, and promising practices.

For Thousand Currents, drawing on generalized knowing means lifting up the wisdom, insights, and experiences of their partners in the field and learning from them. As Bhansali observes, it’s the “social movements and grassroots organizations that actually do the terrific work that’s reflected in [our] theory of change.” In creating a theory of change, Thousand Currents wanted to surface what they do from the perspective of their grantee partners, fine-tune what they say they do and how they represent it, and then choose what they were committing to continue doing and measure it. Both theory of change and evaluation are examples of generalized knowing and provide critical insights into strengthening efforts to effect transformative social change.

To surface what they were doing, Thousand Currents did a series of interviews and surveys with grantee partners, as many research projects do. What was different about this project, though, was how it evolved to be in real relationship with the foundational and practical (and even artistic) knowing of their grantee partners, bringing multiple ways of knowing to bear in their ongoing theory of change process.

The theory of change methodology was introduced to Thousand Currents by long-time funder and consultant Shiree Teng during the learning and evaluation journey. According to Teng, Thousand Currents’ theory of change was developed as a tool for learning—identifying patterns, conducting experiments, and making adjustments. It helps the organization have a coherent conversation about what and how it thinks about the world in which it operates, the context it finds itself in, and the assumptions it holds. As Teng says, we don’t often have the opportunity on a weekly or even a monthly basis to say to each other, “Hey, I’m doing these things because I’m assuming these things.” We don’t often pause and consider why we do what we choose to do, or why we do some things over others.

When Thousand Currents got to what they thought was the end of drafting their theory of change and were ready to share it with the world, staff had some reservations. Bhansali reported with a laugh that they were complaining that the theory was too linear and didn’t reflect the adaptive and flexible way that the organization actually works with partners. So, they paused and went back to the stories they heard, and through these stories were able to create an artistic accompaniment to the theory that reflected the team’s more holistic approach.

When the founder of Thousand Currents, Paul Strasburg, first saw the comprehensive theory of change, he remarked, “This is an experience-based model—a model that has grown out of your own continuing trial-and-error experiments over decades… It’s not a hypothesis to be tested but really a culmination of experience…. [with] a higher probability of success than other models that have dominated the field.”

Practical Knowing

“Being in a learning community is different than being in a community of practice. A community of practice is about the learning from the doing. Not the learning about doing.”—Norma Wong

This idea of our organizations and networks being communities of practice that unfold from and in mutual relationship with our foundational, artistic and generalized knowing is one that resonates with Thousand Currents as well. Bhansali reports,

[Our theory of change] is effecting everything from how we do workplans and reporting with our grantee partners, to our internal program and grantmaking processes, to our new capacity building and alliance building work that we have signed up to be accountable for with measurable outcomes, to our own internal budgeting processes. This is where the alignment comes in from our experience through to our action.

Conclusion

“Knowing will be more valid—richer, deeper, more true to life and more useful if…our knowing is grounded in our experience, expressed through our art, understood through theories which make sense to us, and expressed in worthwhile action in our lives.”

— Peter Reason, “A Laypersons’ guide to co-operative inquiry,” University of Bath, 1998

With our clients and partners in the field, we continue to engage in practices that bring forth our multiple ways of knowing. Through this, we are creating space for all of us to bring our full selves to the tables so that together we can continue to—in the words of Dr. King—bend the long arc of history toward justice. As our understanding and practices deepen, the possibility for justice seems within closer reach.

The authors would like to thank featured contributor Rajiv Khanna. Khanna is the Director of Philanthropic Partnerships at Thousand Currents (formerly IDEX), where he leads a team engaged in resource mobilization and building a philanthropic community that has forged solidarity-based learning partnerships with Global Southern grassroots groups. A recovering academic, Rajiv is professionally trained as a historian of international relations, has taught in public universities, and serves on the Board of Management Assistance Group.

We hope you’re enjoying this series, “Five Elements of a Thriving Justice Ecosystem,” which began with “Pursuing Deep Equity” and led to “Cultivating Leaderful Ecosystems.” Look for the next part, “Influencing Complex Systems Change,” next week.