July 5, 2016; Atlantic

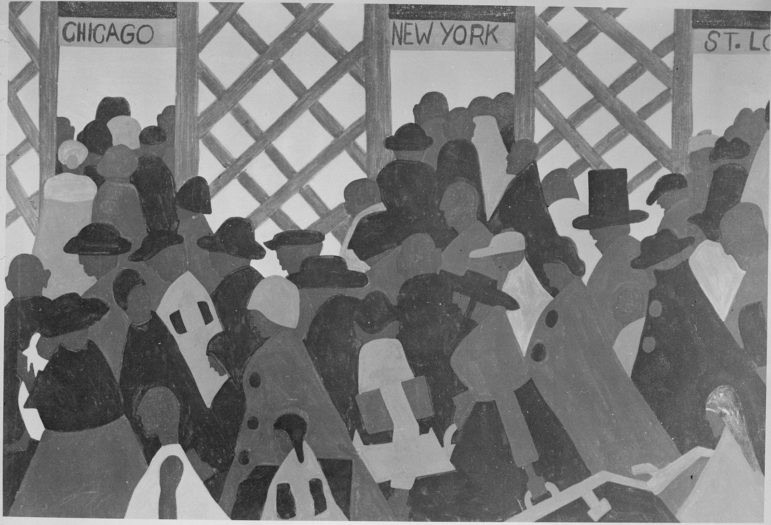

From 1916 to 1970, more than six million African Americans moved north from the rural South in what was called the Great Migration. Reasons cited for this movement included harsh Jim Crow laws and a lack of economic opportunity. Many people found relief in Northern and Midwestern cities, which had a great need for industrial workers during the beginning of the 20th century.

A hundred years later, many of these cities are witnessing an exodus dubbed “The New Great Migration.” Cities like Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and even New York City have lost many thousands of black residents over the last decade while Southern cities like Atlanta, Houston, and Dallas have seen a surge of black residents during the same period. USA Today reports that the five cities with the greatest loss of African-American residents are New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Detroit, while the top five cities that have experienced the most significant growth in African-American residents are Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Miami, and Washington D.C.

This new migration is being led by college-educated people and retirees, some of whom are returning to the very South they left during the height of the original migration. In the early part of the twentieth century, African Americans looking for opportunity headed north. They could earn more working in factories than they could as sharecroppers. The cities embraced them, glad to have workers to meet the industrial demand. Today, the opposite is occurring. Thousands of black residents left the North over the last decade, with New York losing 67,709 black residents, Chicago losing 58,225, and Detroit losing 37,603. According to USA today, at the last census count New York had the largest African-American population, but the states with second- and third-largest African-American communities are no longer Illinois and California; they are Florida and Texas.

So what’s causing this new Great Migration? One reason frequently cited is a lack of jobs. The average unemployment rate for African Americans in Detroit, St. Louis, and Chicago is 20 percent. Part of this can be attributed to African Americans not fully acquiring the skills required in today’s workforce. While Cleveland was known for factory jobs, in the last 50 years, the city’s employment opportunities moved to healthcare and technology. The Cleveland Clinic is currently the city’s largest employer, followed by the University Hospitals Group.

The cost of housing in Northern cities also influenced the population movement. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that the 2010 median single-family home price in northeastern metropolitan areas was $243,900, compared with $153,700 in southern metro areas, according to the National Association of Realtors. The perception of better schools and social programs in the South along with the warm weather served as additional incentives. Florida attracted more black migrants than any other state over the past decade, reported by the Post-Gazette.

Finally, there is the sentiment that Northern cities value immigrants more than African Americans. Immigrants have a reputation for creating small businesses and reviving decayed urban neighborhoods. Jazmin Long, director of community relations and strategic partnerships for Global Cleveland, seeks to address these tidings. She told the Atlantic, “My work is to dispel those rumors. We have a lot of people who don’t feel welcome here, so we needed to find a way to make African Americans feel comfortable with our work.”

Global Cleveland is one of the nonprofits making an effort to encourage African Americans to stay while recruiting immigrants to the city. Its program called the African-American Initiative partners with Cleveland’s chapter of the NAACP. The goals of this new initiative include:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Connecting the resources of the region and collaborating with existing organizations to attract African-American boomerangs and newcomers to Cleveland.

Collaborating with business partners and nonprofit organizations to recruit African-American talent to fill internship positions within Greater Cleveland.

Fostering an inclusive and welcoming community for African-Americans.

Global Cleveland is also working to increase Black representation on nonprofit boards and in partnership with Cuyahoga County Community College to create workforce training—in particular, for the skills needed for the new manufacturing jobs.

Global Cleveland is also making efforts to ease some racial tensions. One challenge is helping Black residents to understand that welcoming immigrants to the city improves everyone’s chances for a better life. Welcoming Mentors is a new program that recruits volunteers to help orient refugees, immigrants, and international students to their new neighborhoods in Cleveland and seeks to ease the tension they may have with some African-American residents.

While these efforts are showing positive results, much more will be needed to convince African-Americans to remain in Cleveland and other northern cities. With the New Great Migration, political and economic power for African Americans is shifting to the South. Former New Orleans Mayor Marc Morial, who heads the National Urban League, an organization started 100 years ago to help Black newcomers to cities find work, tells USA Today that the New South is “not the South that people left.” He credits the Civil Rights movement and key civil rights legislation drafted 50 years ago with transforming cities like Memphis, Nashville, Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Charlotte into economic powerhouses. “It’s totally different, particularly the big cities,” he says.

But just as with the first Great Migration to the North, perception is everything. Jazmin Long told The Atlantic that if African-Americans feel that Cleveland is a good place to live, they will tell their friends and relatives in other cities. “It’s all about word of mouth,” she says. For the moment, it seems that the word of mouth among African Americans is that the South is better.—Alexis Buchanan