February 4, 2019; Truthout

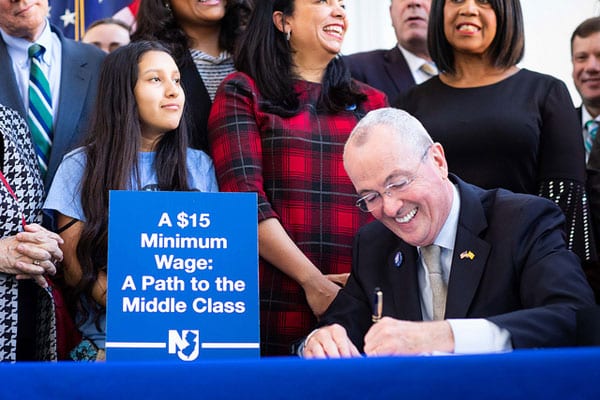

On Monday, New Jersey became the fourth state to raise its hourly minimum wage by a significant amount and commit to a $15 minimum wage in the next few years. The New Jersey Working Families Alliance (NJWFA), New Jersey Education Association, racial justice organizers, clergy members, and others ran a smart movement that achieved this major goal, though advocates say there is plenty more work to be done.

Officially, the wage for most workers will increase to $10 per hour starting July 1st of this year, then increase by $1 an hour every January 1st until 2024, when it will hit $15. After that, minimum wage increases will be indexed to inflation. Agricultural, seasonal, and tipped workers are the notable exceptions. Their wage increases will come later, and they aren’t guaranteed to reach the full $15 hourly minimum. Northjersey.com helpfully reprinted a chart from the Assembly Majority Office showing the different wages and increases over the next few years.

NJWFA has been working on this campaign for years. They almost succeeded a few years ago, but then-governor Chris Christie vetoed the bill, saying that it was too much, too fast, and would hurt small businesses and, ultimately, workers—a common argument by opponents that is contested among economists. (We might argue that if your business model depends upon underpaying your staff, then perhaps it is not as workable as it appears.) NPQ has been following the Fight for $15, an intersectional movement that could improve the lives of women, immigrants, people of color, and other groups that tend to be overrepresented in underpaid jobs.

NJWFA did not give up after Christie’s veto; they moved down a rung of government to where they could find success. Like states that began passing protective laws in the absence of federal leadership, cities and counties began to raise the minimum wage of their workers to set an example for the state.

During the next gubernatorial election campaign, said Analilia Mejia, executive director of NJWFA, the plan was to “inject [the issue] so deeply into both the conversations being had by potential candidates and by our partners and by regular New Jerseyans” that it would “create the inevitability…that’s frankly how we won.”

Mejia said, “We’re really proud of the fact that it’s almost to the finish line.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The groups most left behind in this bill were tipped workers and farmworkers. Farmworkers occupy an odd place in the labor world; according to Craig Garcia and Manuel Guzman, both of whom are labor-organizing leaders,

The exclusion of farmworkers from basic labor standards is, unfortunately, nothing new in the United States. When the right to unionize was codified under the Federal National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), farmworkers were excluded to win over the votes of Southern Democrats—who did not believe that the right to organize should be extended to migrant farmworkers and black sharecroppers.

Legal Services of New Jersey, a nonprofit that provides legal assistance and resources to those who are unable to pay, clarified that “farmworkers in New Jersey have the right to join together to organize, discuss as a group, and bargain with their employer about wage rates and conditions of work.” However, many advocates are still fighting for basic labor protections such as overtime pay.

Tipped workers are another story. Their federal wage is $2.13. and it hasn’t been raised since 1991. As most consumers know, customers are expected to make up the rest through tips. In addition to shifting the burden of labor costs in an enormous industry onto the consumer, this forces poverty and instability on many service workers. According to the Economic Policy Institute,

While the poverty rate of non-tipped workers is 6.5 percent, tipped workers have a poverty rate of 12.8 percent. Tipped workers are thus nearly twice as likely to live in poverty as are non-tipped workers. Yet poverty rates are significantly lower for tipped workers in states where they receive the full regular minimum wage.

This “two-tiered system” is a target for criticism in several places; last week, Rhode Island senator Gayle Goldin announced a bill to eliminate the tiers entirely. “The hospitality industry is predominantly a woman workforce in tipped jobs,” said Goldin, and “We’re no longer requiring these tipped workers to rely on the relationship with the customer.”

Mejia and others are also still fully committed to making sure farm workers’ and tipped workers’ wages rise. “Where there’s a political will, there’s always a way,” said Mejia.—Erin Rubin